Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

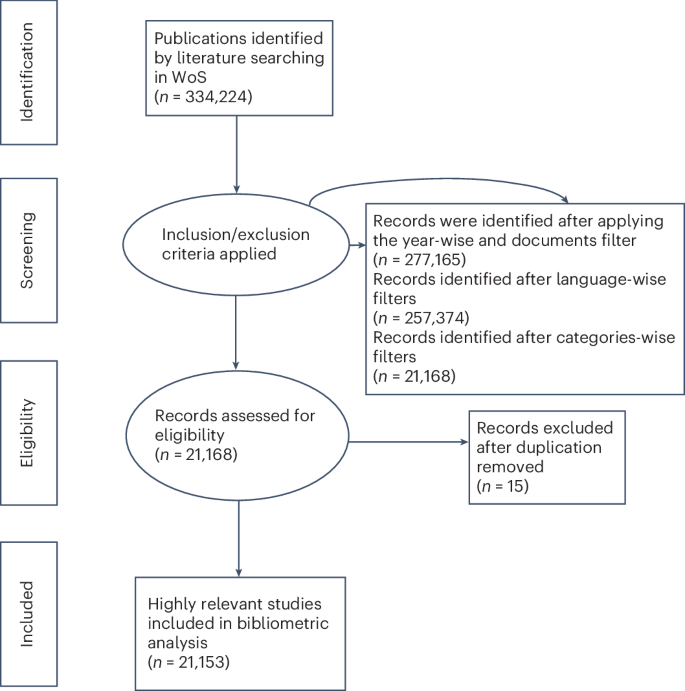

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 70, 2019, review article, how to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses.

- Andy P. Siddaway 1 , Alex M. Wood 2 , and Larry V. Hedges 3

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 70:747-770 (Volume publication date January 2019) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- First published as a Review in Advance on August 08, 2018

- Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- APA Publ. Commun. Board Work. Group J. Artic. Rep. Stand. 2008 . Reporting standards for research in psychology: Why do we need them? What might they be?. Am. Psychol . 63 : 848– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF 2013 . Writing a literature review. The Portable Mentor: Expert Guide to a Successful Career in Psychology MJ Prinstein, MD Patterson 119– 32 New York: Springer, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1995 . The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 : 497– 529 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1997 . Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 3 : 311– 20 Presents a thorough and thoughtful guide to conducting narrative reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ 1995 . Writing a review article for Psychological Bulletin. Psychol . Bull 118 : 172– 77 [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Hedges LV , Higgins JPT , Rothstein HR 2009 . Introduction to Meta-Analysis New York: Wiley Presents a comprehensive introduction to meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Higgins JPT , Hedges LV , Rothstein HR 2017 . Basics of meta-analysis: I 2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 8 : 5– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL , Thoemmes FJ , Rosenthal R 2014 . Continuously cumulating meta-analysis and replicability. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 333– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ 1994 . Vote-counting procedures. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 193– 214 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J 2014 . Priming, replication, and the hardest science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 40– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I 2007 . The lethal consequences of failing to make use of all relevant evidence about the effects of medical treatments: the importance of systematic reviews. Treating Individuals: From Randomised Trials to Personalised Medicine PM Rothwell 37– 58 London: Lancet [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collab. 2003 . Glossary Rep., Cochrane Collab. London: http://community.cochrane.org/glossary Presents a comprehensive glossary of terms relevant to systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn LD , Becker BJ 2003 . How meta-analysis increases statistical power. Psychol. Methods 8 : 243– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2003 . Editorial. Psychol. Bull. 129 : 3– 9 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2016 . Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 5th ed.. Presents a comprehensive introduction to research synthesis and meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM , Hedges LV , Valentine JC 2009 . The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G 2014 . The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 7– 29 Discusses the limitations of null hypothesis significance testing and viable alternative approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Earp BD , Trafimow D 2015 . Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Front. Psychol. 6 : 621 [Google Scholar]

- Etz A , Vandekerckhove J 2016 . A Bayesian perspective on the reproducibility project: psychology. PLOS ONE 11 : e0149794 [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ , Brannick MT 2012 . Publication bias in psychological science: prevalence, methods for identifying and controlling, and implications for the use of meta-analyses. Psychol. Methods 17 : 120– 28 [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL , Berlin JA 2009 . Effect sizes for dichotomous data. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis H Cooper, LV Hedges, JC Valentine 237– 53 New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Garside R 2014 . Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how. Innovation 27 : 67– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Olkin I 1980 . Vote count methods in research synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 88 : 359– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Pigott TD 2001 . The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods 6 : 203– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT , Green S 2011 . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 London: Cochrane Collab. Presents comprehensive and regularly updated guidelines on systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- John LK , Loewenstein G , Prelec D 2012 . Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23 : 524– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Juni P , Witschi A , Bloch R , Egger M 1999 . The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 282 : 1054– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Klein O , Doyen S , Leys C , Magalhães de Saldanha da Gama PA , Miller S et al. 2012 . Low hopes, high expectations: expectancy effects and the replicability of behavioral experiments. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 : 6 572– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Lau J , Antman EM , Jimenez-Silva J , Kupelnick B , Mosteller F , Chalmers TC 1992 . Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 327 : 248– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Light RJ , Smith PV 1971 . Accumulating evidence: procedures for resolving contradictions among different research studies. Harvard Educ. Rev. 41 : 429– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW , Wilson D 2001 . Practical Meta-Analysis London: Sage Comprehensive and clear explanation of meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Matt GE , Cook TD 1994 . Threats to the validity of research synthesis. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 503– 20 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE , Lau MY , Howard GS 2015 . Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean?. Am. Psychol. 70 : 487– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Hopewell S , Schulz KF , Montori V , Gøtzsche PC et al. 2010 . CONSORT explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340 : c869 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Liberati A , Tetzlaff J , Altman DG PRISMA Group. 2009 . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339 : 332– 36 Comprehensive reporting guidelines for systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A , Polisena J , Husereau D , Moulton K , Clark M et al. 2012 . The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 28 : 138– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LD , Simmons J , Simonsohn U 2018 . Psychology's renaissance. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 511– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Noblit GW , Hare RD 1988 . Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies Newbury Park, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Olivo SA , Macedo LG , Gadotti IC , Fuentes J , Stanton T , Magee DJ 2008 . Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 88 : 156– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Open Sci. Collab. 2015 . Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 : 943 [Google Scholar]

- Paterson BL , Thorne SE , Canam C , Jillings C 2001 . Meta-Study of Qualitative Health Research: A Practical Guide to Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Patil P , Peng RD , Leek JT 2016 . What should researchers expect when they replicate studies? A statistical view of replicability in psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 539– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R 1979 . The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 86 : 638– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL , Rosenthal R 1989 . Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. Am. Psychol. 44 : 1276– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson S , Tatt ID , Higgins JP 2007 . Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 36 : 666– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R , Crooks D , Stern PN 1997 . Qualitative meta-analysis. Completing a Qualitative Project: Details and Dialogue JM Morse 311– 26 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE , Rodgers JL 2018 . Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 487– 510 [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W , Strack F 2014 . The alleged crisis and the illusion of exact replication. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 59– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF , Berlin JA , Morton SC , Olkin I , Williamson GD et al. 2000 . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE): a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283 : 2008– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S , Jensen L , Kearney MH , Noblit G , Sandelowski M 2004 . Qualitative meta-synthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual. Health Res. 14 : 1342– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Tong A , Flemming K , McInnes E , Oliver S , Craig J 2012 . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12 : 181– 88 [Google Scholar]

- Trickey D , Siddaway AP , Meiser-Stedman R , Serpell L , Field AP 2012 . A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32 : 122– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC , Biglan A , Boruch RF , Castro FG , Collins LM et al. 2011 . Replication in prevention science. Prev. Sci. 12 : 103– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Forms and templates

Image: David Parmenter's Shop

- PICO Template

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- Database Search Log

- Review Matrix

- Cochrane Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies

• PRISMA Flow Diagram - Record the numbers of retrieved references and included/excluded studies. You can use the Create Flow Diagram tool to automate the process.

• PRISMA Checklist - Checklist of items to include when reporting a systematic review or meta-analysis

PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: Common Questions on Tracking Records and the Flow Diagram

- PROSPERO Template

- Manuscript Template

- Steps of SR (text)

- Steps of SR (visual)

- Steps of SR (PIECES)

|

Image by | from the UMB HSHSL Guide. (26 min) on how to conduct and write a systematic review from RMIT University from the VU Amsterdam . , (1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319854352 . (1), 49-60. . (4), 471-475. (2020) (2020) - Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews (2017) - Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews (2011) - Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care (2008) |

|

| entify your research question. Formulate a clear, well-defined research question of appropriate scope. Define your terminology. Find existing reviews on your topic to inform the development of your research question, identify gaps, and confirm that you are not duplicating the efforts of previous reviews. Consider using a framework like or to define you question scope. Use to record search terms under each concept. It is a good idea to register your protocol in a publicly accessible way. This will help avoid other people completing a review on your topic. Similarly, before you start doing a systematic review, it's worth checking the different registries that nobody else has already registered a protocol on the same topic. - Systematic reviews of health care and clinical interventions - Systematic reviews of the effects of social interventions (Collaborative Approach to Meta-Analysis and Review of Animal Data from Experimental Studies) - The protocol is published immediately and subjected to open peer review. When two reviewers approve it, the paper is sent to Medline, Embase and other databases for indexing. - upload a protocol for your scoping review - Systematic reviews of healthcare practices to assist in the improvement of healthcare outcomes globally - Registry of a protocol on OSF creates a frozen, time-stamped record of the protocol, thus ensuring a level of transparency and accountability for the research. There are no limits to the types of protocols that can be hosted on OSF. - International prospective register of systematic reviews. This is the primary database for registering systematic review protocols and searching for published protocols. . PROSPERO accepts protocols from all disciplines (e.g., psychology, nutrition) with the stipulation that they must include health-related outcomes. - Similar to PROSPERO. Based in the UK, fee-based service, quick turnaround time. - Submit a pre-print, or a protocol for a scoping review. - Share your search strategy and research protocol. No limit on the format, size, access restrictions or license.outlining the details and documentation necessary for conducting a systematic review: , (1), 28. |

| Clearly state the criteria you will use to determine whether or not a study will be included in your search. Consider study populations, study design, intervention types, comparison groups, measured outcomes. Use some database-supplied limits such as language, dates, humans, female/male, age groups, and publication/study types (randomized controlled trials, etc.). | |

| Run your searches in the to your topic. Work with to help you design comprehensive search strategies across a variety of databases. Approach the grey literature methodically and purposefully. Collect ALL of the retrieved records from each search into , such as , or , and prior to screening. using the and . | |

| - export your Endnote results in this screening software | Start with a title/abstract screening to remove studies that are clearly not related to your topic. Use your to screen the full-text of studies. It is highly recommended that two independent reviewers screen all studies, resolving areas of disagreement by consensus. |

| Use , or systematic review software (e.g. , ), to extract all relevant data from each included study. It is recommended that you pilot your data extraction tool, to determine if other fields should be included or existing fields clarified. | |

| Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment - (download the Excel spreadsheet to see all data) | Use a Risk of Bias tool (such as the ) to assess the potential biases of studies in regards to study design and other factors. Read the to learn about the topic of assessing risk of bias in included studies. You can adapt ( ) to best meet the needs of your review, depending on the types of studies included. |

| - - - | Clearly present your findings, including detailed methodology (such as search strategies used, selection criteria, etc.) such that your review can be easily updated in the future with new research findings. Perform a meta-analysis, if the studies allow. Provide recommendations for practice and policy-making if sufficient, high quality evidence exists, or future directions for research to fill existing gaps in knowledge or to strengthen the body of evidence. For more information, see: . (2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.2450/2012.0247-12 - Get some inspiration and find some terms and phrases for writing your manuscript - Automated high-quality spelling, grammar and rephrasing corrections using artificial intelligence (AI) to improve the flow of your writing. Free and subscription plans available. |

| - - | 8. Find the best journal to publish your work. Identifying the best journal to submit your research to can be a difficult process. To help you make the choice of where to submit, simply insert your title and abstract in any of the listed under the tab. |

Adapted from A Guide to Conducting Systematic Reviews: Steps in a Systematic Review by Cornell University Library

|

This diagram illustrates in a visual way and in plain language what review authors actually do in the process of undertaking a systematic review. |

This diagram illustrates what is actually in a published systematic review and gives examples from the relevant parts of a systematic review housed online on The Cochrane Library. It will help you to read or navigate a systematic review. |

Source: Cochrane Consumers and Communications (infographics are free to use and licensed under Creative Commons )

Check the following visual resources titled " What Are Systematic Reviews?"

- Video with closed captions available

- Animated Storyboard

|

Image: | - the methods of the systematic review are generally decided before conducting it.

Source: Foster, M. (2018). Systematic reviews service: Introduction to systematic reviews. Retrieved September 18, 2018, from |

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Next: Framing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Aug 26, 2024 12:37 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR

Systematic Reviews

Aims and scope.

The journal publishes high quality systematic review products including systematic review protocols, systematic reviews related to a very broad definition of human health, (animal studies relevant for human health), rapid reviews, updates of already completed systematic reviews, and methods research related to the science of systematic reviews, such as decision modelling. At this time Systematic Reviews does not accept reviews of in vitro studies. The journal also aims to ensure that the results of all well-conducted systematic reviews are published, regardless of their outcome. (You can now also prospectively register these reviews on PROSPERO.)

Trending articles

Click here to view which articles have been shared the most in the last month!

- Most accessed

Examining the effectiveness of food literacy interventions in improving food literacy behavior and healthy eating among adults belonging to different socioeconomic groups- a systematic scoping review

Authors: Arijita Manna, Helen Vidgen and Danielle Gallegos

Knowledge and practices of youth awareness on death and dying in school settings: a systematic scoping review protocol

Authors: Emilie Allard, Clémence Coupat, Sabrina Lessard, Noémie Therrien, Claire Godard-Sebillotte, Dimitri Létourneau, Olivia Nguyen, Andréanne Côté, Gabrielle Fortin, Serge Daneault, Maryse Soulières, Josiane Le Gall and Sylvie Fortin

Evaluating the effectiveness of large language models in abstract screening: a comparative analysis

Authors: Michael Li, Jianping Sun and Xianming Tan

Prevalence of human filovirus infections in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol

Authors: Christopher S. Semancik, Christopher L. Cooper, Thomas S. Postler, Matt Price, Heejin Yun, Marija Zaric, Monica Kuteesa, Nina Malkevich, Andrew Kilianski, Swati B. Gupta and Suzanna C. Francis

Patients’ experiences of mechanical ventilation in intensive care units in low- and lower-middle-income countries: protocol of a systematic review

Authors: Mayank Gupta, Priyanka Gupta, Preeti Devi, Utkarsh, Damini Butola and Savita Butola

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement

Authors: David Moher, Larissa Shamseer, Mike Clarke, Davina Ghersi, Alessandro Liberati, Mark Petticrew, Paul Shekelle and Lesley A Stewart

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

Authors: Matthew J. Page, Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, Roger Chou, Julie Glanville, Jeremy M. Grimshaw, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, Manoj M. Lalu, Tianjing Li…

The Editorial to this article has been published in Systematic Reviews 2021 10 :117

Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study

Authors: Wichor M. Bramer, Melissa L. Rethlefsen, Jos Kleijnen and Oscar H. Franco

PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews

Authors: Melissa L. Rethlefsen, Shona Kirtley, Siw Waffenschmidt, Ana Patricia Ayala, David Moher, Matthew J. Page and Jonathan B. Koffel

Drug discontinuation before contrast procedures and the effect on acute kidney injury and other clinical outcomes: a systematic review protocol

Authors: Swapnil Hiremath, Jeanne Françoise Kayibanda, Benjamin J. W. Chow, Dean Fergusson, Greg A. Knoll, Wael Shabana, Brianna Lahey, Olivia McBride, Alexandra Davis and Ayub Akbari

Most accessed articles RSS

Sign up to receive article alerts

Systematic Reviews is published continuously online-only. We encourage you to sign up to receive free email alerts to keep up to date with all of the latest articles by registering here .

Peer review mentoring

The Editors endorse peer review mentoring of early career researchers. Find out more here

Article collections

Thematic series The role of systematic reviews in evidence-based research Edited by Professor Dawid Pieper and Professor Hans Lund

Thematic series Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care Evidence Reviews Edited by Assoc Prof Craig Lockwood

Thematic series Automation in the systematic review process Edited by Prof Joseph Lau

Thematic series Five years of Systematic Reviews

View all article collections

Latest Tweets

Your browser needs to have JavaScript enabled to view this timeline

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

- Follow us on Twitter

Annual Journal Metrics

Citation Impact 2023 Journal Impact Factor: 6.3 5-year Journal Impact Factor: 4.5 Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP): 1.919 SCImago Journal Rank (SJR): 1.620

Speed 2023 Submission to first editorial decision (median days): 92 Submission to acceptance (median days): 296

Usage 2023 Downloads: 3,531,065 Altmetric mentions: 3,533

- More about our metrics

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

| Hours | |

|---|---|

| 7:30am – 2:00am | |

| 7:30am – 2:00am | |

| 7:30am – 2:00am | |

| 8:00am – 5:00pm | |

| Reference Desk | 9:00am – 10:00pm |

Systematic Reviews

- Review Types

- Scoping Review Steps

- Before You Begin

P = Plan: decide on your search methods

I = identify: search for studies that match your criteria, e = evaluate: exclude or include studies, c = collect: extract and synthesize key data, e = explain: give context and rate the strength of the studies, s = summarize: write and publish your final report.

- Biomedical & Public Health Reviews

Congratulations!

You've decided to conduct a Systematic Review! Please see the associated steps below. You can follow the P-I-E-C-E-S = Plan, Identify, Evaluate, Collect, Explain, Summarize system or any number of systematic review processes available (Foster & Jewell, 2017) .

P = Plan: decide on your search methods

Determine your Research Question

By now you should have identified gaps in the field and have a specific question you are seeking to answer. This will likely have taken several iterations and is the most important part of the Systematic Review process.

Identify Relevant Systematic Reviews

Once you've finalized a research question, you should be able to locate existing systematic reviews on or similar to your topic. existing systematic reviews will be your clues to mine for keywords, sample searches in various databases, and will help your team finalize your review question and develop your inclusion and exclusion criteria. , decide on a protocol and reporting standard, your protocol is essentially a project plan and data management strategy for an objective, reproducible, sound methodology for peer review. the reporting standard or guidelines are not a protocols, but rather a set of standards to guide the development of your systematic review. often they include checklists. it is not required, but highly recommended to follow a reporting standard. .

Protocol registry: Reviewing existing systematic reviews and registering your protocol will increase transparency, minimize bias, and reduce the redundancy of groups working on the same topics ( PLoS Medicine Editors, 2011 ). Protocols can serve as internal or external documents. Protocols can be made public prior to the review. Some registries allow for keeping a protocol private for a set period of time.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (UGA Login) (Health Sciences)

A collection of regularly updated, systematic reviews of the effects of health care. New reviews are added with each issue of The Cochrane Library Reviews mainly of randomized controlled trials. All reviews have protocols.

PROSPERO (General)

This is an international register of systematic reviews and is public.

Campbell Corporation (Education & Social Sciences)

Topics covered include Ageing; Business and Management; Climate Solutions; Crime and Justice; Disability; Education; International Development; Knowledge Translation and Implementation; Methods; Nutrition and Food Security; Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity; Social Welfare; and Training.

Systematic Review for Animals and Food (Vet Med & Animal Science)

Reporting Standards:

Campbell MECCIR Standards (Education & Social Sciences)

Cochrane Guides & Handbooks (Health & Medical Sciences)

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies: Finding What Works in Healthcare: Standards for Systematic Reviews (healthcare)

- PRISMA for Systematic Review Protocols (General)

- PRISMA Checklist (General)

- PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (General)

Decide on Databases and Grey Literature for Systematic Review Research

Because the purpose of a SR is to find all studies related to your research question, you will need to search multiple databases. You should be able to name the databases you are already familiar with using. Your librarian will be able to recommend additional databases, including some of the following:

- PubMed (Health Sciences)

- Web of Science

- Cochrane Database (Biomedical)

- National and Regional Databases (i.e. WHO LILACS scientific health information from Latin America and the Caribbean countries)

- CINAHL (Health Sciences)

- PsycINFO (Psychology)

Depending on your topic, you may want to search clinical trials and grey literature. See this guide for more on grey literature.

Develop Keywords and Write a Search Strategy

Go here for help with writing your search strategy

Translate Search Strategies

Each database you use will have different methods of searching and resulting search strings, including syntax. ideally you will create one master keyword list and translate it for each database. below are tools to assist with translating search strings. .

Includes syntax for Cochrane Library, EBSCO, ProQuest, Ovid, and POPLINE.

The IEBH SR-Accelerator is a suite of tools to assist in speeding up portions of the Systematic Review process, including the Polyglot tool which translates searches across databases.

University of Michigan Search 101 - SR Database Cheat Sheet

Storing, Screening and Full-Text Screening of Your Citations

Because systematic review literature searches may produce thousands of citations and abstracts, the research team will be screening and systematically reviewing large amounts of results. During screening , you will remove duplicates and remove studies that are not relevant to your topic based on a review of titles and abstracts. Of what remains, the full-text screening of the studies will then need to be conducted to confirm that they fit within your inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The results of the literature review and screening processes are best managed by various tools and software. You can also use a simple form or table to log the relevant information from each study. Consider whether you will be coding your data during the extraction process in your decision on which tool or software to use. Your librarian can consult on which of these is best suited to your research needs.

- EndNote Guide (UGA supported citation tracking software) - great for storing, organizing, and de-duplication

- RefWorks Guide (UGA supported citation tracking software) - great for storing, organizing, and de-duplication

- Rayyan (free service) - great for initial title/abstract screening OR full-text screening as cannot differentiate; not ideal for de-duplication

- Covidence (requires a subscription) - full suite of systematic review tools including meta-analysis

- Combining Software (EndNote, Google Forms, Excel)

- Forms such as Qualtrics (UGA EITS software) can note who the coder is, creates charts and tables, good when have a review of multiple types of studies

Data Extraction

Data extraction processes differ between qualitative and quantitative evidence syntheses. In both cases, you must provide the reader with a clear overview of the studies you have included, their similarities and differences, and the findings. Extraction should be done in accordance to pre-established guidelines, such as PRISMA.

Some systematic reviews contain meta-analysis of the quantitative findings of the results. Consider including a statistician on your team to complete the analysis of all individual study results. Meta-analysis will tell you how much or what the actual results is across the studies and explains results in a measure of variance, typically called a forest plot.

Systematic review price models have changed over the years. Previously, you had to depend on departmental access to software that would cost several hundred dollars. Now that the software is cloud-based, tiered payment systems are now available. Sometimes there is a free tier level, but costs go up for functionality, number or users, or both. Depending on the organization's model, payments may be monthly, annual or per project/review.

- Always check your departmental resources before making a purchase.

- View all training videos and other resources before starting your project.

- If your access is limited to a specific amount of time, wait to purchase until the appropriate work stage

Software list

Tool created by Brown University to assist with screening for systematic reviews.

- Cochrane's RevMan

Review Manager (RevMan) is the software used for preparing and maintaining Cochrane Reviews.

Systematic review tool intended to assist with the screening and extraction process. (Requires subscription)

- Distiller SR

DistillerSR is an online application designed specifically for the screening and data extraction phases of a systematic review (Requires subscription) Student and Faculty tiers have monthly pricing with a three month minimum. Number of projects is limited by pricing.

- EPPI Reviewer (requires subscription, free trial)

It includes features such as text mining, data clustering, classification and term extraction

Rayyan is a free web-based application that can be used to screen titles, abstracts, and full text. Allows for multiple simultaneous users.

- AHRQ's SRDR tool (free) which is web-based and has a training environment, tutorials, and example templates of systematic review data extraction forms

"System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information, the Joanna Briggs Institutes premier software for the systematic review of literature."

- Syras Pricing is based on both number of abstracts and number of collaborators. The free tier is limited to 300 abstracts and two collaborators. Rather than monthly pricing, the payment is one-time per project.

Evidence Synthesis or Critical Appraisal

PRISMA guidelines suggest including critical appraisal of the included studies to assess the risk of bias and to include the assessment in your final manuscripts. There are several appraisal tools available depending on your discipline and area of research.

Simple overview of risk of bias assessment, including examples of how to assess and present your conclusions.

CASP is an organization that provides resources for healthcare professionals, but their appraisal tools can be used for varying study types across disciplines.

From the Joanna Briggs Institute: "JBI’s critical appraisal tools assist in assessing the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers."

Johns Hopkins Evidence-Based Practice Model (health sciences)

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

Document the search; 5.1.6. Include a methods section

List of additional critical appraisal tools from Cardiff University.

Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

Prepare your process and findings in a final manuscript. Be sure to check your PRISMA checklist or other reporting standard. You will want to include the full formatted search strategy for the appendix, as well as include documentation of your search methodology. A convenient way to illustrate this process is through a PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Attribution: Unless noted otherwise, this section of the guide was adapted from Texas A&M's "Systematic Reviews and Related Evidence Syntheses"

- << Previous: Before You Begin

- Next: Biomedical & Public Health Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2024 1:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.libs.uga.edu/SystematicReview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to write a systematic review

Affiliations.

- 1 The Methodist Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Center, Houston, Texas [email protected].

- 2 Sports Medicine Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

- 3 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

- 4 Sports Medicine Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

- PMID: 23925575

- DOI: 10.1177/0363546513497567

Background: The role of evidence-based medicine in sports medicine and orthopaedic surgery is rapidly growing. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are also proliferating in the medical literature.

Purpose: To provide the outline necessary for a practitioner to properly understand and/or conduct a systematic review for publication in a sports medicine journal.

Study design: Review.

Methods: The steps of a successful systematic review include the following: identification of an unanswered answerable question; explicit definitions of the investigation's participant(s), intervention(s), comparison(s), and outcome(s); utilization of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines and PROSPERO registration; thorough systematic data extraction; and appropriate grading of the evidence and strength of the recommendations.

Results: An outline to understand and conduct a systematic review is provided, and the difference between meta-analyses and systematic reviews is described. The steps necessary to perform a systematic review are fully explained, including the study purpose, search methodology, data extraction, reporting of results, identification of bias, and reporting of the study's main findings.

Conclusion: Systematic reviews or meta-analyses critically appraise and formally synthesize the best existing evidence to provide a statement of conclusion that answers specific clinical questions. Readers and reviewers, however, must recognize that the quality and strength of recommendations in a review are only as strong as the quality of studies that it analyzes. Thus, great care must be used in the interpretation of bias and extrapolation of the review's findings to translation to clinical practice. Without advanced education on the topic, the reader may follow the steps discussed herein to perform a systematic review.

Keywords: PRISMA; PROSPERO; evidence-based medicine; meta-analysis; systematic review.

© 2013 The Author(s).

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Systematic Reviews in Sports Medicine. DiSilvestro KJ, Tjoumakaris FP, Maltenfort MG, Spindler KP, Freedman KB. DiSilvestro KJ, et al. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Feb;44(2):533-8. doi: 10.1177/0363546515580290. Epub 2015 Apr 21. Am J Sports Med. 2016. PMID: 25899433 Review.

- Reporting and methodological quality of systematic reviews in the orthopaedic literature. Gagnier JJ, Kellam PJ. Gagnier JJ, et al. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Jun 5;95(11):e771-7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00597. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013. PMID: 23780547

- Evaluating characteristics of PROSPERO records as predictors of eventual publication of non-Cochrane systematic reviews: a meta-epidemiological study protocol. Ruano J, Gómez-García F, Gay-Mimbrera J, Aguilar-Luque M, Fernández-Rueda JL, Fernández-Chaichio J, Alcalde-Mellado P, Carmona-Fernandez PJ, Sanz-Cabanillas JL, Viguera-Guerra I, Franco-García F, Cárdenas-Aranzana M, Romero JLH, Gonzalez-Padilla M, Isla-Tejera B, Garcia-Nieto AV. Ruano J, et al. Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 9;7(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0709-6. Syst Rev. 2018. PMID: 29523200 Free PMC article.

- Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management: part 6. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Manchikanti L, Datta S, Smith HS, Hirsch JA. Manchikanti L, et al. Pain Physician. 2009 Sep-Oct;12(5):819-50. Pain Physician. 2009. PMID: 19787009

- Research Pearls: The Significance of Statistics and Perils of Pooling. Part 3: Pearls and Pitfalls of Meta-analyses and Systematic Reviews. Harris JD, Brand JC, Cote MP, Dhawan A. Harris JD, et al. Arthroscopy. 2017 Aug;33(8):1594-1602. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.01.055. Epub 2017 Apr 27. Arthroscopy. 2017. PMID: 28457677 Review.

- Artificial Intelligence in Emergency Trauma Care: A Preliminary Scoping Review. Ventura CAI, Denton EE, David JA. Ventura CAI, et al. Med Devices (Auckl). 2024 May 23;17:191-211. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S467146. eCollection 2024. Med Devices (Auckl). 2024. PMID: 38803707 Free PMC article. Review.

- Patterns of sedentary behavior among older women with urinary incontinence and urinary symptoms: a scoping review. Leung WKC, Cheung J, Wong VCC, Tse KKL, Lee RWY, Lam SC, Suen LKP. Leung WKC, et al. BMC Public Health. 2024 Apr 30;24(1):1201. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18703-7. BMC Public Health. 2024. PMID: 38689284 Free PMC article. Review.

- The Functional Integrity of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Can Be Objectively Assessed With the Use of Stress Radiographs: A Systematic Review. Schwartz J, Rodriguez AN, Banovetz MT, Braaten JA, Larson CM, Wulf CA, Kennedy NI, LaPrade RF. Schwartz J, et al. Orthop J Sports Med. 2024 Apr 25;12(4):23259671241246197. doi: 10.1177/23259671241246197. eCollection 2024 Apr. Orthop J Sports Med. 2024. PMID: 38680218 Free PMC article.

- Understanding Risk Factors for Suicide Among Older People in Rural China: A Systematic Review. Zhang Q, Li S, Wu Y. Zhang Q, et al. Innov Aging. 2024 Feb 17;8(3):igae015. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igae015. eCollection 2024. Innov Aging. 2024. PMID: 38618517 Free PMC article. Review.

- Writing a Scientific Review Article: Comprehensive Insights for Beginners. Amobonye A, Lalung J, Mheta G, Pillai S. Amobonye A, et al. ScientificWorldJournal. 2024 Jan 17;2024:7822269. doi: 10.1155/2024/7822269. eCollection 2024. ScientificWorldJournal. 2024. PMID: 38268745 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Literature Reviews

- Getting started

What is a literature review?

Why conduct a literature review, stages of a literature review, lit reviews: an overview (video), check out these books.

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Guide Owner

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Definition: A literature review is a systematic examination and synthesis of existing scholarly research on a specific topic or subject.

Purpose: It serves to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge within a particular field.

Analysis: Involves critically evaluating and summarizing key findings, methodologies, and debates found in academic literature.

Identifying Gaps: Aims to pinpoint areas where there is a lack of research or unresolved questions, highlighting opportunities for further investigation.

Contextualization: Enables researchers to understand how their work fits into the broader academic conversation and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

tl;dr A literature review critically examines and synthesizes existing scholarly research and publications on a specific topic to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge in the field.

What is a literature review NOT?

❌ An annotated bibliography

❌ Original research

❌ A summary

❌ Something to be conducted at the end of your research

❌ An opinion piece

❌ A chronological compilation of studies

The reason for conducting a literature review is to:

| What has been written about your topic? What is the evidence for your topic? What methods, key concepts, and theories relate to your topic? Are there current gaps in knowledge or new questions to be asked? | |

| Bring your reader up to date Further your reader's understanding of the topic | |

| Provide evidence of... - your knowledge on the topic's theory - your understanding of the research process - your ability to critically evaluate and analyze information - that you're up to date on the literature |

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

While this 9-minute video from NCSU is geared toward graduate students, it is useful for anyone conducting a literature review.

Writing the literature review: A practical guide

Available 3rd floor of Perkins

Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences

Available online!

So, you have to write a literature review: A guided workbook for engineers

Telling a research story: Writing a literature review

The literature review: Six steps to success

Systematic approaches to a successful literature review

Request from Duke Medical Center Library

Doing a systematic review: A student's guide

- Next: Types of reviews >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:40 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

The process to select eligible RCTs is shown.

Lines indicate point estimates; shaded areas, 95% CIs.

eFigure. Defining Eligible Randomized Clinical Trials

eTable. Factors Associated With Citation of Systematic Reviews

Data Sharing Statement

- Should a Systematic Review Be Required in a Clinical Trial Report? JAMA Network Open Invited Commentary March 23, 2023 Ivo Abraham, PhD; Matthias Calamia, PharmD; Karen MacDonald, PhD

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Jia Y , Li B , Yang Z, et al. Trends of Randomized Clinical Trials Citing Prior Systematic Reviews, 2007-2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e234219. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.4219

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Trends of Randomized Clinical Trials Citing Prior Systematic Reviews, 2007-2021

- 1 Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen, China

- 2 Department of Public Health and Primary Care, School of Clinical Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 3 Center for Diversity in Public Health Leadership Training, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland

- 4 Department of Cardiology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia

- 5 M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, Villanova University, Villanova, Pennsylvania

- 6 Section Evidence-Based Practice, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway

- 7 School of Public Health and Primary Care, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

- 8 Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland

- Invited Commentary Should a Systematic Review Be Required in a Clinical Trial Report? Ivo Abraham, PhD; Matthias Calamia, PharmD; Karen MacDonald, PhD JAMA Network Open

Question Has the citation of prior systematic reviews in reports of randomized clinical trials improved over time?

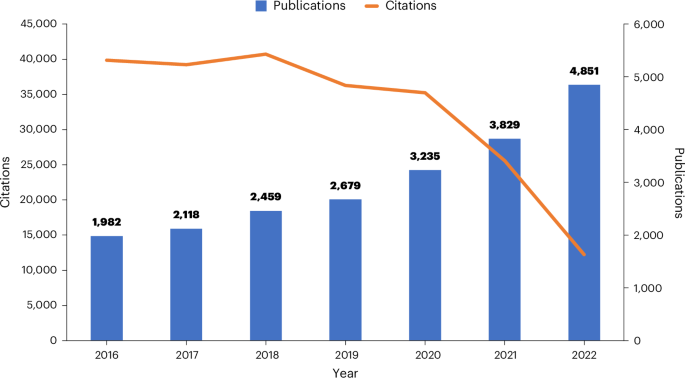

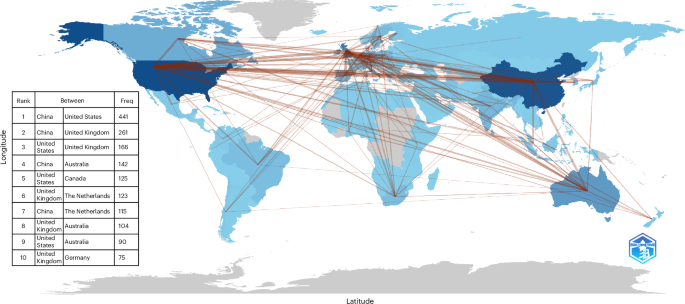

Findings In this cross-sectional study of 4003 randomized clinical trials (RCTs), the percentage of RCTs citing systematic reviews increased from 35.5% in 2007 to 2008 to 71.8% since 2020, with an annual rate of increase of 3.0%. RCTs with 100 participants or more, nonindustry funders, and authors from high-income countries were more likely to cite systematic reviews than those with fewer than 100 participants, industry funders, and authors from low- and middle-income countries.

Meaning These findings suggest that the citation of prior systematic reviews in reports of RCTs has improved over time but may need further improvement.

Importance Systematic reviews can help to justify a new randomized clinical trial (RCT), inform its design, and interpret its results in the context of prior evidence.

Objective To assess trends and factors associated with citing (a marker of the use of) prior systematic reviews in RCT reports.

Design, Setting, and Participants This cross-sectional study investigated 737 Cochrane reviews assessing health interventions to identify 4003 eligible RCTs, defined as those included in an updated version but not in the first version of a Cochrane review and published 2 years after the first version of the Cochrane review was published.

Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcome was the citation of prior systematic reviews, Cochrane or others, as determined by screening references of eligible RCTs. Factors that may be associated with the citation of prior systematic reviews were also examined.

Results Among 4003 eligible RCTs, 1241 studies (31.0%) cited Cochrane reviews, 1698 studies (42.4%) cited prior non-Cochrane reviews, and 2265 studies (56.6%) cited either type of systematic review or both; 1738 RCTs (43.4%) cited no systematic reviews. The percentage of RCTs citing prior Cochrane reviews, non-Cochrane reviews, and either or both types of review increased from 28 studies (15.3%), 46 studies (25.1%), and 65 studies (35.5%) of 183 RCTs before 2008 to 42 studies (40.8%), 65 studies (64.1%), and 73 studies (71.8%) of 102 RCTs since 2020, respectively; the annual increases were 1.9% (95% CI, 1.4%-2.3%), 3.3% (95% CI, 2.9%-3.7%), and 3.0% (95% CI, 2.5%-3.5%), respectively. The proportion of RCTs citating prior systematic reviews varied considerably across clinical specialties, ranging from 28 of 106 RCTs (26.4%) in ophthalmology to 386 of 553 RCTs (69.8%) in psychiatry ( P < .001). RCTs with 100 participants or more (risk ratio [RR], 1.16; 95% CI, 1.03-1.30), nonindustry funding (RR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.27-1.61), and authors from high-income countries (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.03-1.17) were more likely to cite systematic reviews than those with fewer than 100 participants, industry funding, and authors from low- and middle-income countries, respectively. A journal requirement to cite systematic reviews was not associated with the likelihood of citing a systematic review.

Conclusions and Relevance This study found that the citation of prior systematic reviews in RCT reports improved over time, but approximately 40% of RCTs failed to do so. These findings suggest that reference to prior evidence for initiating, designing, and reporting RCTs should be further emphasized to assure clinical relevance, improve methodological quality, and facilitate interpretation of new results.

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) should be justified, designed, and interpreted in the context of prior evidence. 1 - 4 Failure to consider prior evidence may be associated with low clinical relevance, compromised methodological quality, and even redundant RCTs on clinical questions for which sufficient quality evidence is already available. Such studies may waste valuable resources, unnecessarily put patients at potential harm, and damage public trust in scientific research. 5 - 10

According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions , a systematic review “attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits prespecified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question” and is characterized by a clear set of objectives, a reproducible methodology, a comprehensive search, an assessment of the validity of findings, and a systematic presentation. 11 A high-quality and up-to-date systematic review comprehensively synthesizes prior evidence and can help to ensure that new RCTs are worthwhile and informative. 1 - 4 For example, systematic reviews may help justify the necessity of a new trial, plan its sample size, and overcome major methodological problems of prior similar trials. When the new trial is completed, systematic reviews can help assess its outcomes among the overall evidence by comparing and synthesizing its findings with those of prior similar trials.

Making reference to or citing a relevant systematic review in an RCT report may be used as an indication of the use of prior evidence. In the past 2 decades, many stakeholders have endorsed the importance of and made great efforts to promote the citation of prior systematic reviews in RCT reports. For example, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials ( CONSORT ) reporting guideline statement recommends that an RCT report include “a reference to a systematic review of previous similar trials or a note of the absence of such trials.” 12 In 2017, an international group of health research funders called for funding only research that had been set in the context of existing systematic reviews or had robustly demonstrated a research gap. 13 Further, some journals have explicitly required citation of prior relevant systematic reviews since 2010. 14 In addition, researchers have been advocating citing systematic reviews, including through international organizations, such as the Evidence-Based Research Network 15 and EVBRES (Evidence-Based Research) a Cost Action. 1 - 3 , 16

A 2022 study 17 suggested that researchers frequently failed to cite a relevant systematic review. However, it remains unclear whether the reference to prior evidence has improved in RCTs and what factors may be associated with this practice. 17 We thus conducted this study to address these research questions. Objectives were to assess the citation of systematic reviews in RCT reports, compare the citation of systematic reviews in RCT reports across clinical specialties, and assess the factors associated with citing systematic reviews in RCT reports.