Central Park, New York :The sustainable and cultural significance of Central Park on New York

Recreation, rejuvenation, and refreshment- The Central Park in Manhattan, New York is not a “typical park” but a collective product of numerous leisure pursuits and an emotional attachment for the New Yorkers. Spread across 51 blocks through Manhattan , The Central Park New York was built in 1858 on a land of 843 acres including 150 acres of water. “The Green Heart of the Big Apple”, the leafy park can be construed as a spot for entertainment, relaxation, and fun with over 42 million visitors every year.

Who and what inspired the need for this enormous park?

It was in London and Paris! In the 1800s, New Yorkers were highly influenced by the parks around the world and thus declared a competition for the designing of a recreation park that would go on to become the most popular area in Manhattan. An existing village and farmland that was inhabited by Irish immigrants and African Americans, was chosen as the most apparent site for the landscaping. British-American architect Calvert Vaux and Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted won the competition and proclaimed that their project “Greensward” would be “a democratic development of the highest significance,” which meant that it would be accessible to all the citizens of New York, and not just the privileged.

Central Park NY today

Central Park consists of gigantic green spaces , water bodies and over 20,000 trees, 30 tennis courts, 21 playgrounds, and 26 ball fields. More than a park, space is an amalgamation of activities ideal for people of all ages and an antidote for the congestion and increasing population of New York. A magnet for visitors in and around New York, Central Park also hosts some of the city’s most prominent events (both one-time and recurring) like marathons and concerts which involve the participation of abundant people. This way, the park works as a major boost to the economy of the City and a congregation area with awe-inspiring landscapes and design.

Central Park New York has a lot to offer. Countless pathways with beautiful greenery perfect for a morning jog, several restaurants for a date with your partner, exciting concerts that can be enjoyed with friends, or just a quiet corner by a lake to read your favorite book, the architects of the project have been successful with their vision of creating the most dynamic, interesting and delightful recreational oasis for the people of New York.

Sustainability at Central Park and why is it important.

Before indulging in the sustainability factor at Central Park, one needs to understand the concept of sustainability at an NYC park in general. Some of these factors include: utilizing long-lasting and easy to maintain materials and plants, restoring the natural areas that would protect biodiversity, making attempts to reduce the impact of climate changes, reducing carbon emissions, and engaging the people to participate in keeping the park clean, maintained, and sustainable.

So, what makes Central Park sustainable?

- The people

The massive involvement of the people in maintaining and taking care of the park, like their own, is exceptional. The key factor of sustainability at Central Park is the citizens, volunteers, and members of the Central Park Conservancy that was formed in 1980. The community has raised over $600 million to keep the park running smoothly, cleaning up the garbage, educating others about biodiversity which in turn attracts more visitors. The park is also a win-win situation on all ends- people, the city, and nature.

- Public recycling

New Yorkers love a good barbecue and especially if it is at a public park! These barbeque parties in return produce a large amount of trash that is recyclable. Apart from this, activities like picnics, reading, or even exercise contribute to the $300 million that the City spends on exporting tons of trash to landfills. The City Council has passed legislation in expanding recycling in public areas which helps with effective waste management, as volunteers and organizations like The Green Team actively work towards this goal.

- Leaf composting

Plenty of trees at Central Park produce plenty of leaves that ultimately fall and are collected and taken to landfills because of safety and aesthetic concerns . This move led to the removal of nutrients from nature and led to the need of using extra fertilizers. Several composting techniques like segregating leaves that would go to the landfills and relocating the fallen leaves from lawns and blown into natural areas, help to reuse the leaves instead of letting them go to waste. An organization called the Parks Inspection Program (PIP) provides rating standards that maintain the locating of leaves into planting beds.

The humongous number of trees at Central Park contributes to the freshness and cleanliness of the air and makes the park cooler as well. New York is often regarded as an “urban heat island” which makes it hotter than its surroundings due to the extensive use of heat-absorbing materials like concrete and glass, and thus the trees work as natural air-conditioners. Apart from these incredible benefits, trees also capture air pollutants; reduce the number of toxins flowing into the water bodies, and filter rainwater that helps in maintaining the landscape .

Home to many wildlife species like ducks, fish, squirrels, and chipmunks, there are over 230 different species of birds that rely on the park’s water bodies throughout the year. Central Park is a dream for every New Yorker that wants to spend time outdoors and away from city life as it provides space for innumerable activities and recreation. The green jungle amidst the concrete jungle, the park is a boon to the health of the City and the people keeping its surroundings cleaner and healthier.

Aishwarya Khurana is an architect and creative writer, who likes to express herself through humor, words, and quirky ideas. A design enthusiast, butter chicken lover, and music junkie, she loves to read and write about art & architecture and believes that nobody can defeat her in a pop-culture quiz.

15 projects by WDG Architecture

9 different cultures that have influenced the architecture of Europe

Related posts.

Trends in Sustainable Architecture

Sustainability and Universal Design: Accessibility of Green Buildings

Integrating Traditional Water Systems into Contemporary Urban Design

Using Technology to Improve Urban Life

Architectural evolution of Kaunas City, 1919-1939

From Heat Islands to Urban Oases: Strategies for Designing Cooler Cities

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Looking for Job/ Internship?

Rtf will connect you with right design studios.

A breath of fresh air, NYC’s Central Park

This iconic park set the standard for public spaces

Aerial view of Central Park, New York City (photo: © Ester Inbar )

In the center of Manhattan Island lies a great expanse of sculpted nature. This large swath of greenery—Central Park—was the first great manifesto of a new urban vision that sought to introduce nature into the heart of commercial and industrial cities in the United States. As a measure of its tremendous success, the park quickly and enduringly became one of the most popular public attractions in New York City and an icon of a metropolis often famed more for its commercial power than for its art.

Nature and the city

A design of the magnitude and distinction of Central Park is necessarily the product of a fortuitous set of historical conditions. First, and broadly speaking, the park is an expression of the American fascination with the natural landscape that had defined the national character since colonial times. Although it was widely recognized that commercial cities had always been necessary, nineteenth-century American art, literature, politics, and popular culture all celebrated rural land as a central element of the nation’s “exceptionalism.” Henry David Thoreau, whose book Walden (1854) chronicled his retreat for self-renewal in rural Massachusetts, suggested every American city should be obliged to set aside land for a “primitive forest” in order to “preserve all the advantages of living in the country.”

View of Central Park, New York City (photo: alan-light , CC BY 2.0)

The second crucial factor, by the middle of the nineteenth century, was the widespread awareness that industrial cities needed to be carefully planned. Reformers such as the poet and newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant and the travel writer, horticulturalist, and co-designer of Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted embraced the urban future, but they wanted to better the lives of all city dwellers by introducing nature as an antidote to what they saw as the unsafe and unsanitary qualities of large cities. Of course, these reformers knew that true rustic nature was impossible in the middle of cities. Instead, they sought to cultivate a man-made, pastoral landscape that captured the best qualities of nature as filtered through human invention and design. Large parks were to be “the lungs of the city.” The reformers professed a Romantic conviction that being surrounded by nature assuaged the nerves and mind and helped “unbend” certain physical and psychological tensions.

View of a grove with schist outcropping, Central Park, New York City (photo: kpaulus , CC BY 2.0)

Some reformers, though, expressed their views in a more paternalistic manner, showing disdain toward the poor and working classes. They argued that Central Park’s bucolic scenery should serve as a setting to refine the coarse, impolite manners thought to characterize especially the new, often impoverished immigrants then found in large cities like New York. Olmsted himself wrote that “a large part of the people of New York are ignorant” of a park’s social purpose and needed “to be trained in the proper use of it.” Olmsted’s original objective was to direct visitors to stroll through Central Park and quietly admire the natural scenery; they were not to partake, as they often do today, in strenuous exercise, large festivals or concerts, or any other behavior that would disturb the park’s bucolic ambience. Early on, he and his design partner Calvert Vaux issued regulations to achieve the desired behavior among park visitors: a polite sociability that might then filter out into behavior in the city itself.

The English landscape

View of sheltered valley, Leonardslee Gardens, England (photo: ukgardenphotos , CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

These social concerns relied on the aesthetics of the natural landscape pioneered earlier in England. The “English landscape gardens” of the eighteenth century, as well as the early nineteenth-century suburban cemeteries of Paris, especially Père-Lachaise, strongly influenced landscape design in the United States. In the 1830s, for example, the Rural Cemetery Movement produced important landscape designs including Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Green-Wood in Brooklyn (below), and Laurel Hill in Philadelphia. These suburban cemeteries were intended to provide a quiet retreat and confer physical and mental health benefits on visitors. They were designed according to the aesthetics of the English landscape garden (above), in which winding paths, open meadows, ponds, and occasional architectural “follies” created picturesque effects very different from the rigidly symmetrical or geometrical layouts of gardens in the Italian and French traditions, such as the Boboli Gardens in Florence or the royal gardens at Versailles.

Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, 1836 (photo: Dave Bledsoe , CC: BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Politics and Central Park

Political support was the third major factor in Central Park’s development. The land acquired for the park had been included in the city’s gridded urban plan of 1811, which was an early effort to take control of Manhattan Island’s development. The area was treeless, rocky terrain. On the west side it encompassed a small settlement that counted 264 residents in the 1855 census. About half of the modest houses in “Seneca Village,” as it was known, were owned by free African Americans, along with many German and Irish immigrants. There were at least two churches, cemeteries, and a school. City and state government used the legal power of eminent domain to claim the land as part of Central Park, forcibly evicting all the residents by 1857.

Frederick Law Olmsted, plan, 1869 ( larger image available )

New York engineer Egbert Viele—who was responsible for the first, unbuilt plan for Central Park in 1856—described the land as a “pestilential spot” with “miasmatic odors” emanating from the untended ground. Unhealthy and unsightly, the land was ripe for reform as projections for Manhattan’s future growth pushed the boundary of built-up land further and further north. Reformers and politicians also soon realized that the 1811 plan had not sufficiently taken account of the need for recreational and other types of open space. Even the few parks provided by that plan had mostly been built over in the intervening decades as real estate interests trumped the public good.

In 1853, after more than a decade of agitation by Bryant, landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing, and others, the state of New York authorized the creation of a large park in Manhattan, originally to be built and designed by Viele. However, his design was considered perfunctory, offering little in the way of artistry or ingenuity. The Central Park Commissioners, as the governmental body was known, appointed Frederick Law Olmsted as superintendent of works and called for an open competition for a new design.

Olmsted was not a designer or engineer. He had been a farmer and horticultural enthusiast on Staten Island for several years before traveling in northern Europe, Mexico, and elsewhere. His travels inspired him to take up writing and, later, magazine publishing. Calvert Vaux approached Olmsted about jointly submitting a design to the park competition. Vaux, an English architect, had earlier worked in partnership with Downing and eagerly took up the latter’s Romantic ideas about landscape. His partnership with Olmsted resulted in a pairing of like-minded, strong-willed individuals determined to mold the park to their shared vision.

Calvert Vaux, Gothic Bridge, Central Park, New York City (photo: Bryan Schorn , CC BY-SA 3.0)

Olmsted and Vaux won the design competition with their “Greensward Plan,” the last of thirty-two to be submitted. Two elements distinguished the Greensward design from those of their competitors. One was the sheer allure of their landscape features, conveyed in twelve before-and-after panels included in their submission. The other was the ingenious separation of pedestrian and cross-park carriage (now vehicular) traffic.

65th Street transverse in red (detail), Frederick Law Olmsted, Central Park Plan, 1869

The competition brief had insisted that four roadways should connect the east and west sides of Manhattan through the park. All other submissions put those roads on the ground surface, effectively dividing the park into five zones separated by street traffic. However, Olmsted and Vaux submerged their “transverse” roads below ground level and created a continuous expanse of park differentiated by designed topography. As they discovered during construction, this critical invention gave them the chance to increase the park’s picturesque scenery since the many drives and walking paths that cross over the transverses and bridal paths could be embellished by attractive bridges.

Sheep Meadow, Central Park, New York City (photo: yourdon , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

From south to north, the park is laid out to create distinct visual experiences, helping the visitor navigate the vast space and creating picturesque variety in strong contrast to the rectilinearity of the gridded city around it. South of the reservoirs—there were originally three but today only the largest irregular one remains as a lake—the park is a series of pastoral areas, including the large glade called the Parade Ground (now the Sheep Meadow) surrounded by copses or small groves of trees (above).

The Mall, Central Park, New York City (photo: chrisschoenbohm , CC BY-NC 2.0)

In the southern end of the park, we find one area that departs from the naturalism: the long, tree- and bench-lined Promenade now know as the Mall (above) which leads to the Terrace and Bethesda Fountain (below).

Major and Knapp Engraving, Manufacturing, and Lithographic Company, The Terrace , 1869, color lithograph

Emma Stebbins, Angel of Waters, 1873, bronze, Bethesda Fountain (photo: Wayne Noffsinger , CC BY 2.0)

The Terrace is divided into upper and lower sections, a remarkably classical environment with wide, symmetrical stairs and a sense of formality. Jacob Wrey Mould, an English architect who worked on the park for Olmsted and Vaux until 1874, designed its ornament. A surprising and elegant space, the Terrace is a delightful foil to the landscape around it. At its center is the much-photographed fountain surmounted by sculptor Emma Stubbins’ Angel of the Waters , installed in 1873 (left). Between the Terrace steps is the Arcade, a long subterranean space with a stunning ceiling decorated with tiles designed by Mould and manufactured by the Minton Tile Works in England. The formal but festive appearance of the Terrace is appropriate for a space conceived as the city’s “open air hall of reception.”

North of the Lake is the Ramble, a series of small, twisting paths along rocky outcroppings of the local stone, called schist, that can be seen throughout the park. At the northernmost edge of the park is the most rugged landscape with the densest foliage, then and now the park’s least visited section. But the area offers some of the park’s most stunning features, including the Ravine with its small brook, waterfalls, and tomb-like Glen Span Arch, made from massive, rough-faced stones. The quiet of the area is an almost haunting experience; it feels much more secluded than its actual distance from the busy surrounding streets would suggest.

Glen Span Arch, Central Park, New York City (photo: gigi_nyc , CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The park’s influence

Central Park was very much a product of its particular moment in time, a combination of aesthetic ideas, urban concerns, and political will that coalesced in the decade before the Civil War. Its instant success led to other opportunities for Olmsted and Vaux to apply their approach to landscape design: a few of the important projects were Prospect Park in Brooklyn (1866-73), the Buffalo park system (begun 1868), and the suburb of Riverside, Illinois (1868).

Later, working apart from Vaux, Olmsted had a flourishing practice: he designed the campus of Stanford University (1889), the Druid Hills district in Atlanta (1892), and the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893)—just three among many projects. The landscape philosophy developed by Olmsted and Vaux and first expressed at Central Park had lasting influence, inspiring, for instance, Jens Jensen’s “prairie landscapes” in Chicago and elsewhere in the early twentieth century. It was arguably no exaggeration when Harper’s Magazine declared in 1862 that Central Park was “the finest work of art ever executed in this country.” It may still be.

Essay by Paul A. Ranogajec

The Central Park website

Industrialization and Conflict in America, 1840-70, on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Morrison H. Heckscher, Creating Central Park (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008).

Francis R. Kowsky, Country, Park & City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992).

David Schuyler, The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986).

Robert Twombly, ed. Frederick Law Olmsted: Essential Texts (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010).

Find this essay in...

Seeing america.

- Theme: Geography and the Environment

- Period: 1848 - 1877

- Topic: City and country

Art histories

- Olmsted and Vaux, Central Park

Explore the diverse history of the United States through its art. Seeing America is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Alice L. Walton Foundation.

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Toggle navigation

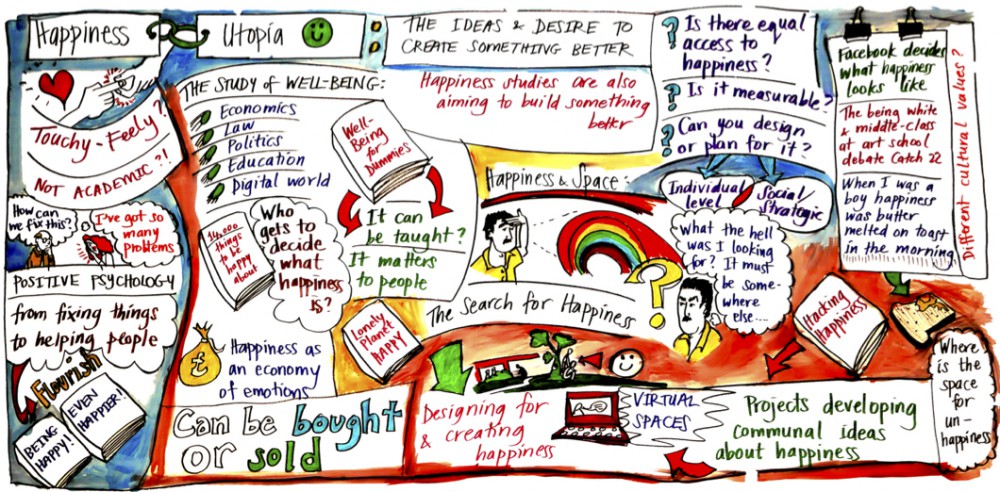

The Composition of Happiness

Eng 1101 / hus 1101 learning community (fall 2014).

My Happy Place: Central Park

Out of the many places I have visited in New York my favorite place that brings me happiness is Central Park. Central Park is a calm place full of nature located right in the center of the chaotic city of Manhattan. I have lived in New York for about 15 years and I still have not visited all of central park because it is huge. My goal is to someday finally say that I have been all around central park.

In my opinion Central Park is one of the most beautiful places in New York City. It is gorgeous year around, it is always perfect to go to central park. In the summer anyone could go take a walk, ride bikes, roller blade, claim rocks or even just sit down on top of the huge rocks overlooking at the skyscrapers enjoying a picnic. In the fall the leaves start to change colors and start to fall down. Taking a walk down the park hearing the crunching noise of the leaves on the ground while looking over the trees made up of all the different shades of red. In the in the winter the tress get covered with snow. It seems as if you were walking down a winter wonderland. I love watching people playing with the snow such as snow ball fighting, making snowmen, or making snow angles. In the spring flowers start to bloom and trees come back to life. Central park started to bloom back to life with delicate pastel colors such as lavender, pinks, yellows, and greens. It doesn’t matter what season of the year it is I will always love to visit Central Park because of the beautiful view of nature and the tranquility it transmits to me.

Not only does it look beautiful but it also has a lot of sentimental values. Ever since I could remember my parents used to take me and my siblings to Central Park on their days off. My siblings and I used to run around playing tag in the play grounds, racing up the rocks, committing on who learned how to ride a bike faster. I also remember going to the zoo and feeding the animals. After a long week of parents working we took a day off to go relax and spend time together sitting in the grass with snacks enjoying the beautiful weather. Once we got a dog we used to go take him for walks and try to teach him how to play fetch but he never learned.

As time passed we all grew up and stopped going to Central Park as frequently as we used to. Still to this day I love going to Central Park on my free time because it brings back childhood memories. I also love going to just take a break from all the chaos in my life and just sit down and enjoy nature. In the winter I also go to the ice skating rank with friends. Central Park is a place that makes me happy because there is endless things to do. It is also a place that has a lot of sentimental value.

Profile cancel

Email Not published

The OpenLab at City Tech: A place to learn, work, and share

The OpenLab is an open-source, digital platform designed to support teaching and learning at City Tech (New York City College of Technology), and to promote student and faculty engagement in the intellectual and social life of the college community.

New York City College of Technology | City University of New York

Accessibility

Our goal is to make the OpenLab accessible for all users.

Learn more about accessibility on the OpenLab

Creative Commons

- - Attribution

- - NonCommercial

- - ShareAlike

© New York City College of Technology | City University of New York

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Why is New York City important in the United States?

- What is the average temperature of New York City?

Central Park

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Smarthistory - A breath of fresh air, NYC’s Central Park

- Official Site of Central Park, New York City, New York, United States

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention - Central Park

Recent News

Central Park , largest and most important public park in Manhattan , New York City . It occupies an area of 840 acres (340 hectares) and extends between 59th and 110th streets (about 2.5 miles [4 km]) and between Fifth and Eighth avenues (about 0.5 miles [0.8 km]). It was one of the first American parks to be developed using landscape architecture techniques.

In the 1840s the increasing urbanization of Manhattan prompted the poet-editor William Cullen Bryant and the landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing to call for a new, large park to be built on the island. Their views gained widespread support, and in 1856 most of the park’s present land was bought with about $5,000,000 that had been appropriated by the state legislature. The clearing of the site, which was begun in 1857, entailed the removal of a bone-boiling works, many scattered hovels and squalid farms, free-roaming livestock, and several open drains and sewers. A plan was devised by the architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux that would preserve and enhance the natural features of the terrain to provide a pastoral park for city dwellers; in 1858 the plan was chosen from 33 submitted in competition for a $2,000 prize. During the park’s ensuing construction millions of cartloads of dirt and topsoil were shifted to build the terrain, about 5,000,000 trees and shrubs were planted, a water-supply system was laid, and many bridges, arches, and roads were constructed.

The completed Central Park officially opened in 1876, and it is still one of the greatest achievements in artificial landscaping. The park’s terrain and vegetation are highly varied and range from flat grassy swards, gentle slopes, and shady glens to steep, rocky ravines. The park affords interesting vistas and walks at nearly every point. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is in the park, facing Fifth Avenue. There are also a zoo , an ice-skating rink, three small lakes, an open-air theatre, a band shell, many athletic playing fields and children’s playgrounds, several fountains, and hundreds of small monuments and plaques scattered through the area. There are also a police station, several blockhouses dating from the early 19th century, and “ Cleopatra’s Needle ” (an ancient Egyptian obelisk). The park has numerous footpaths and bicycle paths, and several roadways traverse it.

The 98-story Central Park Tower, located one block south of the park, is one of the world’s tallest buildings and the second tallest building in New York City, second only to One World Trade Center .

Twenty Beloved New York Writers on the Magic of Central Park

By maria popova.

In Central Park: An Anthology ( public library ), Andrew Blauner collects twenty paeans to this one particular, and particularly beloved, part of the city by twenty of its most celebrated authors. Adrian Benepe promises in the introduction:

Reading this volume is a little like a walk in the park with some truly excellent companions… . It underscores the fact that Central Park is not simply a geographic destination, nor just the essential masterpiece of landscape architecture and great creative accomplishments of the nineteenth century. Once you add people and time, it becomes a ever-evolving work of art and performance art. It is central to our thinking, our style, and our magnificence.

And the slim but potent volume lives up to that promise.

In “Through the Children’s Gate,” Adam Gopnik brings a dimensional lens to one of New Yorkers’ most persistent and enduring laments: the city’s inescapable pace of change, with its embedded nostalgia for what once was and never will again be:

Still, croissants and crime are not lifestyle choices, to be taken according to taste; the reduction of fear, as anyone who has spent time in Harlem can attest, is a grace as large as any imaginable. To revise Chesterton slightly: People who refuse to be sentimental about the normal things don’t end up being sentimental about nothing; they end up being sentimental about anything, shedding tears over old muggings and the perfect, glittering shards of the little crack vials, sparkling like diamonds in the gutter. Où sont les neiges d’antan? : Who cares if the snows were all of cocaine? We saw them falling and our hearts were glad. […] It is a strange thing to be the serpent in one’s own garden, the snake in one’s own grass. The suburbanization of New York is a fact, and a worrying one, and everyone has moments of real disappointment and distraction. The Soho where we came of age, with its organic intertwinings of art and food, commerce and cutting edge, is unrecognizable to us now— but then that Soho we knew was unrecognizable to its first émigrés, who by then had moved on to Tribeca. This is only to say that in the larger, inevitable human accounting of New York, there are gains and losses, a zero sum of urbanism: The great gain of civility and peace is offset by a loss of creative kinds of vitality and variety. (There are new horizons of Bohemia in Brooklyn and beyond, of course, but Brooklyn has its bards already, to sing its streets and smoke, as they will and do. My heart lies with the old island of small homes and big buildings, the sounds coming from one resonating against the sounding board of the other.) But those losses are inevitably specific. There is always a new New York coming into being as the old one disappears. And that city— or cities; there are a lot of different ones on the same map— has its peculiar pleasures and absurdities as keen as any other’s. The one I awakened to, and into— partly by intellectual affinity, and much more by the ringing of an alarm clock every morning at seven— was the civilization of childhood in New York. The phrase is owed to Iona Opie, the great scholar of children’s games and rhymes, whom I got to interview once. “Childhood is a civilization with its own rules and rituals,” she told me, charmingly but flatly, long before I had children of my own. “Children never refer to each other as children. They call themselves, rightly, people, and tell you what it is that people like them— their people— believe and do.” The Children’s Gate exists; you really can go through it.

In “Framed in Silver,” Mark Helprin reflects on the park through the dusty photographs of his own childhood:

My father and I are in Central Park, on the path that leads from the playground at Ninety-third Street toward the Reservoir. I am about two. It is not long after the war, still the first half of the twentieth century. I know nothing of what has passed. You can see in his face that as someone who was born as the century turned, my father knows perhaps too much. I know nothing of what is to come. Having lived through the great wars and the small, he does. We are walking together, he in a double-breasted great coat, I in an absurd snowsuit. He has a Liberty of London scarf, and his hair is still as black as it was in the desert. I come up to his midthigh, a hood surrounds my face, and on top of it, and my head, is a pompom. We have passed the playground that was the setting of my first dream, in which I flew from one outcropping of granite to another. Unknowing of the nature of dreams, when I awoke I believed that I had actually flown. I’m holding my father’s hand, or, rather, he is holding mine, which disappears quite easily in his. Confident of his absolute protection, I think that as long as I am tethered and close, nothing can ever hurt me. He knows better. Although I dreamed that I could fly, I would not have dreamed that someday I would look back upon the invisible paths made by those whom I love and who are gone, that the picture in which I am walking in Central Park with my father would darken over time, like a clock about to mark the inevitable moment in which I will rejoin him. And then, perhaps as now I am aware of the invisible paths made by others, still others might feel, like the breeze you cannot see, the invisible paths made by me.

In “The Colossus of New York,” Colson Whitehead paints a mosaic portrait of the archetypes you’re promised to encounter in the park — the hipsters, the socialite ladies, the entitled parents, the photographers, the lovers. And, of course, the runners:

SO MANY PEOPLE running. Is something chasing them. Yes, something different is chasing each of them and gaining slowly. She feels fit and trim. People remove layers one by one the deeper they get into the park. The sweaters keep falling from their waists no matter how they tie them. The matching strides of the jogging pair give no indication that after she tells her secret he will stop and bend and put his palms to his knees. Like some of the trees here, some of today’s miseries are evergreen. Others merely deciduous. This is his tenth attempt to join the jogging culture. This latest outfit will do the trick. Pant and heave. How much farther. Reservoir of what. Small devices keep track of ingrown miles. Unfold these laps from their tight circuit to make marathons. It’s his best time yet, never to be repeated. If he had known, he would have saved it for after a hard day at the office or a marital argument. Instead all he has is sweat stains to commemorate. One convert says, I’m going to come here every day from now on. It’s so refreshing.

In “Some Music in the Park,” Francine Prose traces the history of the park as a stage for music and politics:

There was nothing neutral about Nina Simone’s performance. She sang “Strange Fruit,” which is about the bodies of lynching victims hanging from trees in the South. She sang “Four Women,” which is about the oppression— slavery, rape, prostitution— of African American women. She sang “Mississippi Goddam,” a song inspired by the murder of Medgar Evers and the church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four little girls. Every time she said Goddam, she spit the word at the audience. I had never seen a performer, let alone a woman, let alone a black woman, be that angry on stage. She was telling us that, to paraphrase a saying popular in those days, we were not part of the solution; we were part of the problem.

In “The Sixth Borough,” Jonathan Safran Foer (he of Tree of Codes fame) weaves a whimsical alternative mythology, in which a sixth borough mysteriously floats away from the island of Manhattan, but a piece of it is transplanted — literally, lifted off with giant hooks and pulled by the people of New York into its new place — to become what we know as Central Park:

Children were allowed to lie down on the park as it was being moved. This was considered a concession, although no one knew why a concession was necessary, or why it was to children that this concession must be made. The biggest fireworks show in history lighted the skies of New York City that night, and the Philharmonic played its heart out. The children of New York lay on their backs, body to body, filling every inch of the park as if it had been designed for them and that moment. The fireworks sprinkled down, dissolving in the air just before they reached the ground, and the children were pulled, one inch and one second at a time, into Manhattan and adulthood. By the time the park found its current resting place, every single one of the children had fallen asleep, and the park was a mosaic of their dreams. Some hollered out, some smiled unconsciously, some were perfectly still. Was there really a Sixth Borough? There’s no irrefutable evidence. There’s nothing that could convince someone who doesn’t want to be convinced.

Foer does what he does best, grounding the escapist whimsy back into a brilliantly human reality:

[I]t’s hard for anyone, even the most cynical of cynics, to spend more than a few minutes in Central Park without feeling that he or she is experiencing some tense in addition to just the present. Maybe it’s our own nostalgia for what’s past, or our own hopes for what’s to come. Or maybe it’s the residue of the dreams from that night the park was moved, when all of the children of New York City exercised their subconsciouses at once. Maybe we miss what they had lost, and yearn for what they wanted.

In “Fogg in the Park,” Paul Auster juxtaposes the unspoken behavioral governance of the city with the parallel universe of the park:

To walk among the crowd means never going faster than anyone else, never lagging behind your neighbor, never doing anything to disrupt the flow of human traffic. If you play by the rules of this game, people will tend to ignore you. There is a particular glaze that comes over the eyes of New Yorkers when they walk through the streets, a natural and perhaps necessary form of indifference to others. It doesn’t matter how you look, for example. Outrageous costumes, bizarre hairdos, T-shirts with obscene slogans printed across them— no one pays attention to such things. On the other hand, the way you act inside your clothes is of the utmost importance. Odd gestures of any kind are automatically taken as a threat. Talking out loud to yourself, scratching your body, looking someone directly in the eye: these deviations can trigger off hostile and sometimes violent reactions from those around you. You must not stagger or swoon, you must not clutch the walls, you must not sing, for all forms of spontaneous or involuntary behavior are sure to elicit stares, caustic remarks, and even an occasional shove or kick in the shins. I was not so far gone that I received any treatment of that sort, but I saw it happen to others, and I knew that a day might eventually come when I wouldn’t be able to control myself anymore. By contrast, life in Central Park allowed for a much broader range of variables. No one thought twice if you stretched out on the grass and went to sleep in the middle of the day. No one blinked if you sat under a tree and did nothing, if you played your clarinet, if you howled at the top of your lungs. Except for the office workers who lurked around the fringes of the park at lunch hour, the majority of people who came in there acted as if they were on holiday. The same things that would have alarmed them in the streets were dismissed as casual amusements. People smiled at each other and held hands, bent their bodies into unusual shapes, kissed. It was live and let live, and as long as you did not actively interfere with what others were doing, you were free to do what you liked.

What emerges is a meditation on what it means to be oneself:

In the park, I did not have to carry around this burden of self-consciousness. It gave me a threshold, a boundary, a way to distinguish between the inside and the outside. If the streets forced me to see myself as others saw me, the park gave me a chance to return to my inner life, to hold on to myself purely in terms of what was happening inside me. It is possible to survive without a roof over your head, I discovered, but you cannot live without establishing an equilibrium between the inner and outer. […] Perhaps that was all I had set out to prove in the first place: that once you throw your life to the winds, you will discover things you had never known before, things that cannot be learned under any other circumstances.

Like its subject, Central Park: An Anthology is woven of the kind of magic that summons wildly different multiverses and commands them to fold unto each other with fluidity and grace as a single enchanted world unfolds.

— Published July 31, 2012 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/07/31/central-park-anthology-andrew-blauner/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, adam gopnik books culture new york, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

- INTELLIGENT TRAVEL

Behind the Scenes in Central Park

It has been said that Central Park was the first place in New York City where people from all walks of life could gather and relax together. This still rings true today, with the 843-acre park drawing 40 million visitors a year.

More than any other landmark, Central Park reflects the brilliance of New York. And, unlike tourist hotspots like Times Square, Central Park is a favorite among locals — an almost impossibly quiet pause amid the super-urban hoopla. Is there anything more enchanting than strolling along the elm-shaded Mall in the summer, or climbing Belvedere Castle for a view of the Great Lawn ?

Before the Central Park opened, in 1857, the center of Manhattan life was downtown. The park would help drive people uptown with elevated railways and, eventually, upscale apartment buildings like The Dakota . In 1859, Calvert Vaux , an English architect who had never designed a park, and Frederick Law Olmsted , a journalist who had never designed anything at all, won a design contest to improve the park, and the rest, as they say, is history.

In the park’s early years, there were signs saying “no running, no strenuous activity at any time.” Today, the New York City marathon concludes in Central Park, and thousands of people get their daily runs and bike rides in — not to mention the 30 tennis courts, and Pilgrim Hill is a popular spot for sledding in the winter.

The Central Park Conservancy has been responsible for maintaining and preserving the park for decades, and has been credited with bringing it back to its former glory after a period of decay in the 1970s.

How do you keep the most famous park in the world beautiful and running smoothly? The conservancy’s president and CEO, Doug Blonsky , gave me the inside scoop on his labor of love:

Know Your Zones According to Blonsky, the conservancy launched a pioneering “zone management” system in which the park’s 843 acres are divided into 49 zones. Each zone is managed by an expert gardener who makes sure the landscapes and resources in their zone are in tip-top shape. On its busiest day, upwards of 200,000 people pass through Central Park’s gates, “so we do everything to make sure the Park is ready: repair playgrounds and benches, pick up trash, rake leaves, mow lawns, clean water bodies, and so much more,” Blonsky said.

The Park’s Most Popular Spots Blonsky said more than 75 percent of all visitors keep to the South End of Central Park (below 80th Street). Highlights there include Bethesda Terrace , the Great Lawn , Sheep Meadow , and Strawberry Fields — the living memorial to John Lennon.

The “Secret Spot” in Central Park In the North End of the park, you can escape from the city in a way you can’t anywhere else. The pools, stone arches, and dense woodlands there are beautiful. “You’d never know you’re in the middle of Manhattan,” Blonsky said.

Can’t-Miss Trees and Flowers In the spring, Blonsky recommends visiting the Yoshino cherry trees along the east side of the Reservoir , and points out that some of the park’s original oaks can be found in the park’s North End (“They’re nearly 160 years old!”). He said that while visitors often overlook the woodlands on that end of the park, they’re a unique discovery, intended by the park’s original designers to be the “Manhattan Adirondacks.” Tip: Stop by the Charles A. Dana Discovery Center at 110th Street between Lenox Avenue and Fifth Avenue to get the most up-to-date information on the park and its programs.

A Park of Love Central Park has provided a beautiful backdrop for countless weddings and proposals. “One of the most popular places for weddings is the gorgeous Conservatory Garden at 103rd Street and Fifth Avenue,” Blonsky said. “In 2012, 140 weddings took place there – and more than 200 couples took their official wedding photos there.”

Bring Your Binoculars Central Park provides vital stopover grounds where birds can rest and feed during fall and spring migration seasons (approximately 230 different bird species can be found in the park throughout the year). “We introduce and maintain a diverse array of plants to supply food and shelter to animals, including birds,” Blonsky said. To help birders explore the park, the conservancy has developed Discovery Kit backpacks for visitors to borrow, free of charge. “Each one contains binoculars, a guidebook, maps, and sketching materials,” Blonsky said. Pick yours up at Belvedere Castle or the Charles A. Dana Discovery Center.

- Nat Geo Expeditions

A Park for All Seasons Spring and summer bring the most visitors to the park. “To prepare for the crowds, we seed and mow the lawns and keep them closed for the winter so the grass will survive the coldest months,” Blonsky said. The work continue year-round: “All through the winter, we shovel and clear the 51 miles of paths throughout the park,” he said. “We rake the leaves that fall from the park’s more than 21,000 trees throughout autumn, and are continuously maintaining the Park’s 21 playgrounds and 9,000 benches.”

Keeping the Park Healthy The conservancy doesn’t just manage Central Park; it’s also responsible for raising 85 percent of the $46 million it takes to keep it operating each year. “Our two biggest annual fundraisers are Autumn in Central Park , which takes place in November, and the Frederick Law Olmsted Awards Luncheon , which takes place in spring,” Blonsky said. “We also couldn’t do what we do without our 35,000 members .

Free to See Since the park is so large, it’s a good idea to start with a free tour led by the fine folks at the Central Park Conservancy. “As Central Park experts, we love to share our knowledge of the park’s history, its landscapes, its design, and its flora with the public,” Blonsky said. He also recommended downloading the conservancy’s free app . “It helps you search for events, landscapes, and points of interest throughout Central Park,” he said.

Annie Fitzsimmons is Intelligent Travel’s Urban Insider , giving you the dish on the best things to see and do in cities all over the world. Follow her travels on Twitter @anniefitz .

Related Topics

- PEOPLE AND CULTURE

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Central Park in New York City: Everyday Globalities Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The appearance of every human being is not accidental in the world. A code which every living being bears provides the historical background and supposed destiny. That is why things matter in everyday life. From ancient times people attached significance to their location, objects which surrounded them, and the previous elaboration of cultural and traditional variables. This is why the paper is intended to work out the problem of grave influences from the side of everyday locations, objects and things from a man’s environment.

The history of the United States is not so long, but it was preceded by the populations of Native Americans. The foundation of New York City is a versatile scope of different changes in structural peculiarities. The history and legends of NYC are full of different things which influence on global development of mankind of today. It is obvious that the significance of each human being in relation to different places is outlined with a unity of processes which contribute to the global transformations in the world.

According to the rational explanation of every thing to be done for a definite day people do not even think about the invisible truth of how humanity is dependent on the streets and objects being perpetual in peoples’ lives. In this respect the Asian wisdom teaches to choose right location, direction, place in the space etc. The ancient truth seems for the majority of people to be trite and not so authoritative, but, in fact, it is so due to the mutuality of relations between a man and his/her environment.

Looking at such phenomena of life as life cycles and peculiarity of a family to be placed near some objects and places having been chosen by predecessors, or stating perpetual trouble cases, it becomes clear that there is nothing accidental in the world. The chaos theory states, nevertheless, that “simple rules may give rise to complex behavior” and that even a wing beat of butterfly on the one side of ocean may cause tsunami on the other one (Stewart 366).

Thus, I analyzed many places which are more or less connected to my everyday life with their significance for my excellence of living. A man is able to use amenities of life in the technological era. However, more primitive forms of such attitude of people toward a way of life existed long before. New York City is a great location for demonstration of global changes and their vital reflections on today’s prospects of people about how to live. Central Park of New York impresses me most of all in my urbanized life. It is an evidence of how people try to make closer the natural reality to the busy world of present days.

Moreover, this place is visited by most of the people in the city due to its natural sceneries and places where one can just sit down on a bench, breath in air and think over the previous times or future perspectives. It is located in the Uptown of Manhattan and, in fact, it is not the very center of the island (Cannon 190). Its everlasting trees and grass being so attractive for young people and kids is a great place in order to forget about troubles in life. Furthermore, it serves as a better medicine for those being tired due to the existence of small squirrels run here and there across the park. It is also a great opportunity to feed them. All in all, this place is considered to be the most attractive when I am not pressed for time.

The role of a human being visiting this park is not merely an everyday fact. Being in this place one definitely feels the positive energy of everything which surrounds him/her. In this case a man may assume that suchlike individuals contributed to the fulfillment of this place previously. In other words, there is an extra-significance of my personal being in this place. The thing is that Central Park connects people with the whole New York in its diversity of landscape and objects placed in the city. The square form of the park dissolves the coarse pictures of New York. In this respect once again it is necessary to mention that the location of the park is placed in the center of Manhattan, one of the most influential trade, financial, and business centers of the world.

In everyday life we never come across things in isolation from one another, fragments. “Things constantly step back into the referential totality, or, more properly stated, in the immediacy of everyday occupation they never even first step out of it… Things recede into relations” (Cited in Fuller 46).

Living at once in different systems people are trying every day to improve their state of affairs in each of social, economic, or even political system being important for the global development of men’s activity on the whole. In personal attempts to explain how Central Park involves me into the reality of various systems mentioned above it is important to work out use of it by other individuals and a special attention of the city administration toward it. By means of such approach it is possible to point out social and economic reflections which I gain out of the park while constantly visiting it.

The world is a complicated structure with many-faceted character of relationships being connected into different systems. To make such statement easier, I understand my existence in the world and in the Central Park, in particular, as a piece of participation in global super-structural systems which make impacts not only on New York City, but apparently on the whole world’s social and economic milieu. I walk down the park and see how people behave themselves. I look at the glimpses of concrete jungle and tops of skyscrapers through the multiple twigs of the trees and understand that my visits to the park can be taken into account as a “gesture” of participation in social, economic, and political life. Working out this idea I am eager to explain such attitude of mine in detail.

Though, my participation in social development when visiting Central Park is outlined in sharing of the idea about the significance of suchlike time spending for further generations. Moreover, my opinion may also influence on the idea of genuine structure of this sightseeing, its historic and cultural importance, if only somebody wanted to overbuild a part of this green area. “World is understood beforehand when objects encounter us” (Cited in Fuller 46).

I am convinced that the genuine structure and beauty of the park should have no negative changes and be protected by society beginning with me. This is why a man should be understood in a gulf of opportunities and potential which a human being may bear. The reality and history knows many examples when people having little chances to survive succeeded afterwards, and now they are well-known, such as: A. Chekhov, D. Defoe, B. Obama etc.

The economic parallel in visiting Central Park of New York and my person is underlined with the assumption that it is within easy reach from the places where many-million contracts are concluded. In the long or short perspective more visits to Central Park may let me be more interested in business and economic constituent of the national stability. In the global prospects a man’s participation in the economic system can be asserted unintentionally in sharing the ideas that saving this place in its beauty one saves national money, or money of taxpayers.

Prevention from any cases of somebody who wants to destruct something in a park makes my role in the economic processes felt, indeed. Once I stopped some highbinders when they were trying to break twigs of an oak, police officer was already there and punished offenders of the nature. Besides, Central Park is a cultural, traditional, economic, social, and historic heritage of not only New Yorkers, but of the United States, at large.

In political evaluation of this place there is a necessity to mention that Central Park is connected to broader political milieu due to its wonderful place for making speeches and announcements, like in Hyde Park in London. It is also a place where due to the political campaign candidates may show their concernment in this place while planting trees, for example. Such actions may lead toward positive feedbacks from the side of the citizens and, perhaps, the end will be a position in the city’s administration. In my situation once I suggested to promote action for our college president for peers having lunch in the park. It was successful indeed. Afterwards a so-called political campaign was completed successfully.

A rather simple estimation of any place in its relation toward broader system, in order to show how an individual’s everyday life reflects global connections, can be achieved by virtues of more philosophical and sociological approach: “The visual system seems to try to represent an object’s surface properties in a way that is invariant to changes in the imaging environment” (Blakemore 36).

To say more, the destination of the Manhattan Island was in its strategic significance for Native Americans. It is known that today’s Broadway street is placed on the previously made by Native American tribes way to make communication and exchange between tribes possible (Bloom 75). Here is a kind of historical circle, when things are doomed to repeat in accordance with a special destination of place. Central Park is still a reminder of a vivid wood contours of which Manhattan had earlier. Moreover, the energetic magnificence of Central Park makes it a wonderful place because of its correlation with urban part of New York. It is not surprising in this respect to make pa conclusion that NYC is a place where several cultures, systems and peculiarities of peoples’ life are concentrated in a form of a great symbolic juncture, or even “hub” (Cannon 185).

Today Central Park as one of the major parts of New York and Manhattan, particularly, embodies the whole complex of different global connections and provides a wider view on its significance for an individual. Furthermore, such idea is quite emphasized with the fact that almost the whole economic stability is comprised in Manhattan. That is why Central Park demonstrates a transition of cultural and traditional for Americans manners in terms of their love to the nature and capability to practice industrial and economic growth without forgetting about the domain of the nature.

To sum [up, there is a great significance of peoples’ participation in global changes. The thing is that every individual visiting different places involves himself/herself into a dimension of global connections. Thereupon, Central Park in New York City is a great example of how green space measures with urban sceneries and how this place reflects the direct connection to global processes of modern world and Manhattan, particularly.

Works cited

Blakemore, Colin. Vision: coding and efficiency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Bloom, Ken. Broadway: its history, people, and places : an encyclopedia. Ed. 2. London: Taylor & Francis, 2004.

Cannon, Gwen. New York City. Ed. 20. New York: Michelin Apa Publications, 2007.

Fuller, Andrew Reid. Insight into value: an exploration of the premises of a phenomenological psychology. New York: SUNY Press, 1990.

The scenery snapshot of Central Park. Web.

- The Task Force on Inclusivity and Diversity

- Prison: Imprisoning and Alternative Ways

- Neighborhood Pride in New York City

- Alonzo vs. Chase Manhattan Bank, NA Case Study

- Re-Imagining New York: Moving to and from the City

- G. Penrod’s “Anti-Intellectualism: Why We Hate the Smart Kids”

- Importance of the Social Model of Disability

- What Could the Future Inclusive Play Area Look Like?

- Social Work as an Important Element of Society

- The Role of a Student in Society

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 2). Central Park in New York City: Everyday Globalities. https://ivypanda.com/essays/central-park-in-new-york-city-everyday-globalities/

"Central Park in New York City: Everyday Globalities." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/central-park-in-new-york-city-everyday-globalities/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Central Park in New York City: Everyday Globalities'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Central Park in New York City: Everyday Globalities." March 2, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/central-park-in-new-york-city-everyday-globalities/.

1. IvyPanda . "Central Park in New York City: Everyday Globalities." March 2, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/central-park-in-new-york-city-everyday-globalities/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Central Park in New York City: Everyday Globalities." March 2, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/central-park-in-new-york-city-everyday-globalities/.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

When a ‘Be In’ in Central Park Was Front-Page News

Fifty-two years ago, thousands came to Central Park for a counterculture happening that influenced decades of political gatherings there.

By Laura M. Holson

They came wearing crowns of daffodils in their hair, their foreheads painted rainbow blue and gold as they strolled through Central Park, kites drifting overhead. It was March 26, 1967, and more than 10,000 New Yorkers from Brooklyn to the Bronx gathered for a “Be In” on Easter Sunday to spread a message of love and tolerance.

Attendees covered a police car with flowers. They chanted, “L-O-V-E, L-O-V-E, L-O-V-E,” and strummed guitars as police officers kept a watchful eye. Women showed off their Easter bonnets. The New York Times described it at the time as “noisy, swarming, chaotic and utterly surrealistic.” For many it was a reminder that Central Park was a unique place for people to gather in a country divided by race, politics and women’s rights. It was front-page news.

Indeed, a month later, crowds would gather again, but this time their message was more pointed: End the war in Vietnam . That is why the Be-In from March 1967, inspired by an earlier one in San Francisco, was a singular event.

“It represents a cultural moment in our history,” said Marie Warsh, a historian for the Central Park Conservancy, which oversees management of the park. “Central Park became an epicenter of the counterculture in New York, where different people from all walks of life could gather.”

Sure, there were later Be-Ins or happenings in the 1960s. The subsequent rally in 1967 was part of the “ Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam ” and ended with a march to the United Nations, where orators like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke against war. A year later, a peace rally and another Easter Be-In were combined. By 1969, though, the gatherings had become explicitly political.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion? You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Creating Central Park

Morrison h. heckscher, met art in publication.

You May Also Like

"The Metropolitan Museum of Art: An Architectural History"

Augustus Saint-Gaudens: Master Sculptor

American Art Posters of the 1890s in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, including the Leonard A. Lauder Collection

Hudson River School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford

Childe Hassam: American Impressionist

Related content.

- Essay From Geometric to Informal Gardens in the Eighteenth Century

- Essay Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

- Essay From Model to Monument: American Public Sculpture, 1865–1915

- Essay Industrialization and Conflict in America: 1840–1875

———. 2008. Creating Central Park . New York, N.Y. : New Haven, [Conn.]: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

- Newsletters

- Terms of use

- Contributors

Narratives of place: New York’s Highline and Central Park

New York’s Central Park and The Highline are two of the world’s most preeminent examples of urban landscape architecture in the recent history. The former was conceived as way of healing social unrest of the mid-1800s, the latter was a design that preserves a disused railway. Both parks have captured the attention and affection of New Yorkers and tourists alike. Four postgraduate landscape architecture students from the University of Western Australia travelled to New York to explore how the city’s “landscape celebrities” Central Park and the new High Line connect people to the city.

Daybeds in the park offer a rare opportunity for Manhattanites to lounge in the sun.

Image: Iwan Baan

Landscape architecture’s power to connect people to place is exemplified by two of New York’s iconic landscapes: Central Park and The High Line. A recent study trip to the United States gave four postgraduate landscape architecture students from the University of Western Australia an opportunity to explore these key projects, conceived about 150 years apart.

The pedestrian experience of these two sites has become a qualifier for engagement with the narrative of New York on both local and global scales. The sites assist local communities in constructing the city’s identity and successfully market the experience of place to national and global communities. They construct a narrative that connects people to place through both physical experience and the imaginary, informed by the promotion and veneration of these landscapes.

Each project is an exemplar of a place for pedestrians in which the act of “promenading” extends the edges of site into the broader city. The two north–south streets that run parallel to the edge of Central Park, Central Park West and Fifth Avenue, promote movement through Manhattan before one might slip “off the grid” and in to the park’s nooks and crannies. Although more complex to access – once found – a visitor to The High Line is rewarded with an elevated, complex and multilayered experience of promenading.

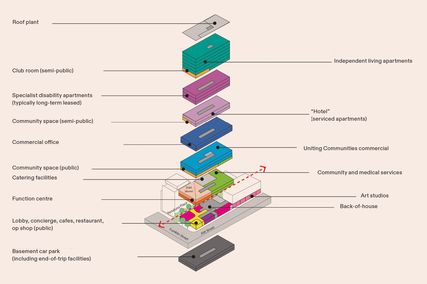

Designed by landscape architect James Corner Field Operations with architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro and planting designer Piet Oudolf , The High Line (2009–2011) is a 1.6-kilometre-long public park built on an elevated and disused 1934 freight rail line in Chelsea, which has been opportunistically and successfully inserted into the dense fabric of contemporary West Side Manhattan. The layered, systems-based insertion is solely for pedestrians.

Daybeds in the park offer a rare opportunity for Manhattanites to lounge in the sun.

It is a post-industrial “celebrity” landscape that offers back-stage views to the landmarks of Manhattan and beyond over the Hudson River to New Jersey. It also provides clandestine views into apartment windows, service docks and otherwise unseen machinations of the city. Many of the collective nodes along The High Line are visually voyeuristic, as in the instance of the glass-windowed theatre overlooking Tenth Avenue. In contrast, the same landscape provides multiple places for a solitary figure to pause and reflect, even when crowded, and gives a rare and continuous respite from the street traffic below.

Platforms offer voyeuristic views out to the city traffic below

Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s competition winning grand vision for a 340-hectare Central Park (1858–1873) provided exceptional foresight regarding the future needs of a dense urban population. The Arcadian landscape was designed to improve the lives of urban residents, to rehabilitate the social unrest that resulted for a major wave of immigration to New York City. Similarly, The Higline has accelorated the gentrification of its neighbourhood the Meatpacking District, and more importantly, engaged the disadvantaged residents of the area in a meaningful urban activation.

Ice skating in Central Park.

Image: Linda Cheng

Central Park it has come to embody far more than a pastoral landscape for the lone city dweller. Olmsted and Vaux integrated a complex hierarchy of circulation routes, of which the pedestrian network is just one. Vehicular, bicycle and horse-and-carriage traffic were also sufficiently catered for and continue in the park today. Like The High Line, the park is as much about the collective experience as it is about the absence thereof. The park is punctuated by moments of collective activity; from formal promenading along the Mall walkway to Bethesda Fountain, to relaxing on the Great Lawn tucked in behind The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Baseball, ice rinks and roller discos give way to bird watching, squirrel chasing and solitary reflection offered by the conduit of less-formal spaces. Ever present are the tips of skyscrapers poking through trees, which form a unique and remarkable backdrop.

Central Park and The High Line sit at two ends of a design spectrum in approach, yet they share critical experiences. One is Picturesque, the other Post-Industrial, and each shares nostalgia for nature as a backdrop to interpret, embrace and survive the city. One took 150 years for the trees to mature, the other was inserted as an instant landscape, yet both are recognized as destinations unique and integral to contemporary New York. Most importantly for the role of landscape, the influence these two sites exert on connecting the global community to the city has been phenomenal, raising them to the equivalent of landscape celebrities. These projects demonstrate that the power of landscape to connect is not bound by scale, time or formation. Landscape allows people to connect with the city when it facilitates, strengthens – and in some cases creates – a shared narrative of place.

Robert Hammond, co-founder and former executive director of Friends of the Highline, was in Melbourne in October 2013 speaking on the innovative business model that brought The Highline to life. In a panel discussion chairdd by Rob Gell, Hammond answers the question, are there lessons from The Highline for Melbourne?

Published online: 20 Mar 2014 Words: Simon Kilbane , Josephine Neldner , Sara Padgett Kjaersgaard , Gerard Siero Images: Iwan Baan, Josephine Neldner, Linda Cheng , Padgett Kjqersgaard, Simon Kilbane

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2013

Related topics

More discussion.

“To cut the carbon that goes into buildings to net zero, we need radical change,” writes Philip Oldfield, Gerard Reinmuth and William Craft.

To capitalise on the opportunity presented by the increasing recognition of architecture’s social impact, we need to shift the ways we demonstrate our value, says …

Latest on site

Latest Products

The Highline is an elevated linear park occupying a disused freight railway line in Lower Manhattan.

A pocket of greenery in a densely urbanized city.

Platforms offer voyeuristic views out to the city traffic below

The Standard Hotel straddles The Highline at West 13 th Street

The Highline runs through the industrial Meatpacking District in West Manhattan.

Central Park is bordered by Fifth Avenue on the east side - a wide promenade known to tourists as Museum Mile.

The 18-acre Central Park Lake was an essential part of Olmstead and Vaux’s design.

Bethesda Fountain, Central Park.

Ice skating in Central Park.

Tell us where we should send the Latest news

Join our architecture and design community for the latest news and reviews. Be first to know.

You may also like other Architecture Media network newsletters:

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Recreation, rejuvenation, and refreshment- The Central Park in Manhattan, New York is not a "typical park" but a collective product of numerous leisure pursuits and an emotional attachment for the New Yorkers. Spread across 51 blocks through Manhattan, The Central Park New York was built in 1858 on a land of 843 acres including 150 acres of water.

The Mall, Central Park, New York City (photo: chrisschoenbohm, CC BY-NC 2.0) In the southern end of the park, we find one area that departs from the naturalism: the long, tree- and bench-lined Promenade now know as the Mall (above) which leads to the Terrace and Bethesda Fountain (below). ... Essay by Paul A. Ranogajec. Go deeper. The Central ...

In my opinion Central Park is one of the most beautiful places in New York City. It is gorgeous year around, it is always perfect to go to central park. In the summer anyone could go take a walk, ride bikes, roller blade, claim rocks or even just sit down on top of the huge rocks overlooking at the skyscrapers enjoying a picnic.

Central Park is located in New York City, and stretches from 59th Street to 110th Street, between Fifth Avenue and Central Park West. ... In one of his most well-known essays he declared that one purpose of parks was to provide "Opportunity and inducement to escape at frequent intervals from the confined and vitiated air of the commercial ...

Central Park, largest and most important public park in Manhattan, New York City. It occupies an area of 840 acres (340 hectares) and extends between 59th and 110th streets (about 2.5 miles [4 km]) and between Fifth and Eighth avenues (about 0.5 miles [0.8 km]). It was one of the first American parks to be developed using landscape architecture ...

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City that was the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the sixth-largest park in the city, containing 843 acres (341 ha), and the most visited urban park in the United States, with an estimated 42 million visitors annually as of 2016.

Only months after the design competition was completed, the first section of the Park—the Lake —opened to the public in 1858. Central Park was built over the next 15 years and cost $14 million, a significant increase from the project's original $5 million budget. The Mall, circa 1902. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Central Park is located in New York City, and stretches from 59th Street to 110th Street, between Fifth Avenue and Central Park West. ... He was a voluminous writer and in numerous essays, reports, and personal communications sought to communicate why public parks were so essential to urban life. ... Founded in 1838, 20 years before Central ...

It was a chilly Saturday night in February and there was more than a foot of snow in Central Park, along with slippery patches of black ice and slushy, calf-high puddles. But some 200 New Yorkers ...

New York has had its share of love letters, old and new and famous and private. In Central Park: An Anthology (public library), Andrew Blauner collects twenty paeans to this one particular, and particularly beloved, part of the city by twenty of its most celebrated authors. Adrian Benepe promises in the introduction: Reading this volume is a little like a walk in the park with some truly ...