Understanding the Working Class

The working class today is much more complex and diverse than the white, male, manufacturing archetype often evoked in popular narratives

Data Capitalism and Algorithmic Racism

Defining the working class.

Social scientists use 3 common methods to define class—by occupation, income, or education—and there is really no consensus about the “right” way to do it. Michael Zweig, a leading scholar in working-class studies, defines the working class as “people who, when they go to work or when they act as citizens, have comparatively little power or authority. They are the people who do their jobs under more or less close supervision, who have little control over the pace or the content of their work, who aren't the boss of anyone." 1

Using occupational data as the defining criteria, Zweig estimated that the working class makes up just over 60 percent of the labor force. 2 The second way of defining class is by income, which has the benefit of being available in both political and economic data sets. Yet defining the working class by income raises complications because of the wide variation in the cost of living in the United States. An annual income of $45,000 results in a very different standard of living in New York City than it does in Omaha, Nebraska. Incomes are also volatile, subject to changes in employment status or the number of hours worked in the household, making it easy for the same household to move in and out of standard income bands in any given year.

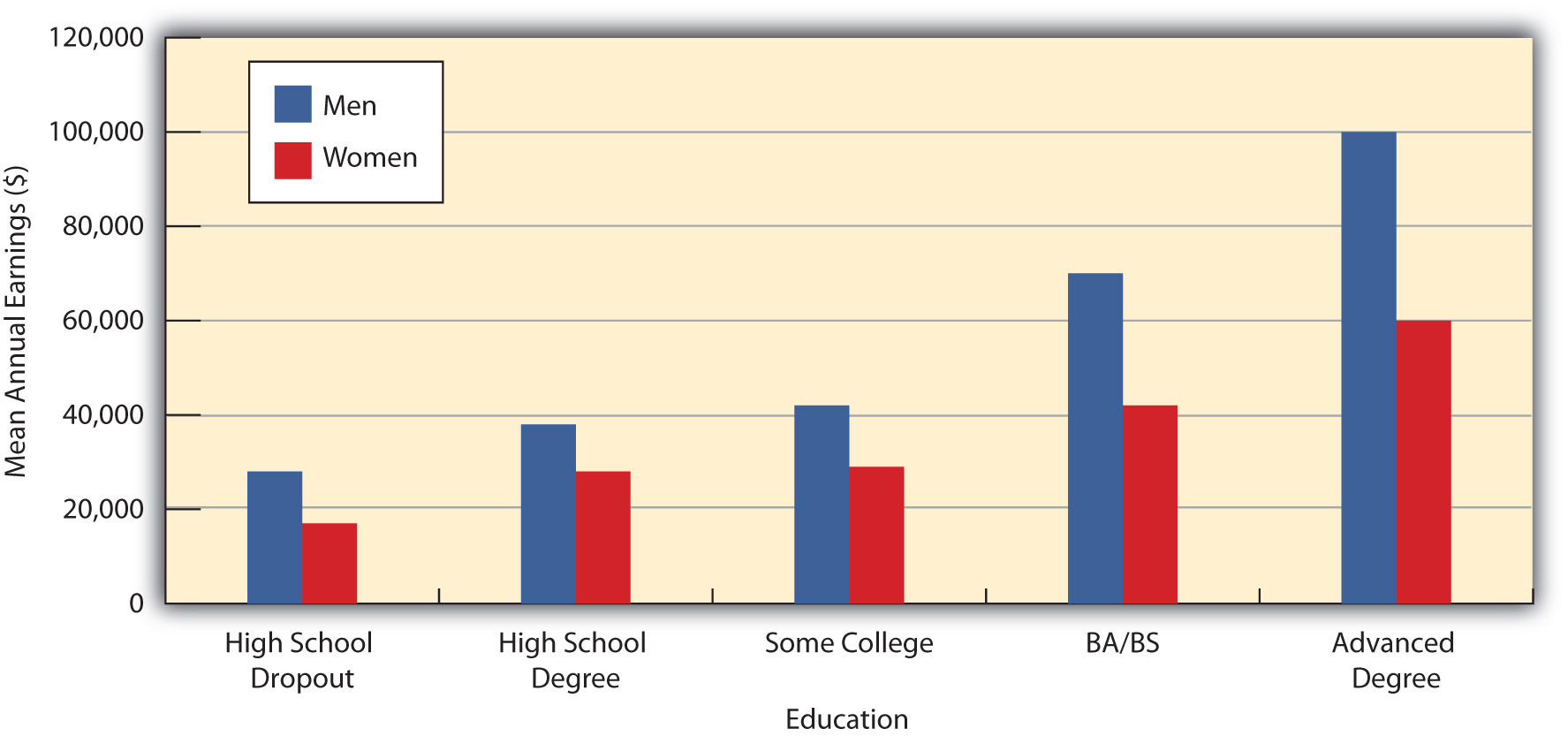

The third way to define class is by educational attainment, which is the definition used in this paper. Education level has the benefit of being consistently collected in both economic and political data sets, but, more importantly, education level is strongly associated with job quality. The reality is that the economic outcomes of individuals who hold bachelor’s degrees and those who don’t have diverged considerably since the late 1970s. While people with bachelor’s degrees experienced real wage growth in the 30 years between 1980 and 2010, incomes among those with only a high school education or some college declined precipitously. Today having a college degree is essential (but no guarantee, of course) to securing a spot among the professional middle class. As unionized manufacturing jobs got sent overseas, the once-blurred lines between occupation and class grew quite sharp. The blue-collar middle class is an endangered species, shrunk to a size that makes it no longer identifiable in national surveys. The downside of using education to define the working class is that education is not a perfect proxy for establishing the power or autonomy one has in the workplace or society—the traditional definition of class. There are definitely well-educated workers who hold menial jobs or jobs that pay low wages, just as there are less well-educated workers who have jobs with great autonomy or power. It is a blunt definition, but in the aggregate it is a reasonably accurate way to distinguish between the working class and the middle class.

In this brief, “working class” is defined as individuals in the labor force who do not have bachelor’s degrees. This includes high school dropouts, high school graduates, people with some college, and associate’s-degree holders. It includes the unemployed, who are counted as still in the labor force as long as they are actively looking for work. Because it is increasingly difficult, and some would argue nearly impossible, to reach the middle class without a bachelor’s degree, the middle class is defined here as workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher. This both distinguishes the types of work performed by the working class and the middle class, and reflects a major distinction in how these different classes of workers earn their pay. Nearly 6 out of 10 workers in America are paid hourly wages, as opposed to annual salaries. 3 And the majority (8 out of every 10) of these hourly workers do not hold a bachelor’s degree. As a result of the divergence in economic fates experienced by those with and without bachelor’s degrees, today’s middle class is overwhelmingly a professional class, comprising workers who get paid annual salaries, work in an office setting, and most assuredly do not have to ask permission to take a bathroom break.

The Demographics of the Working Class

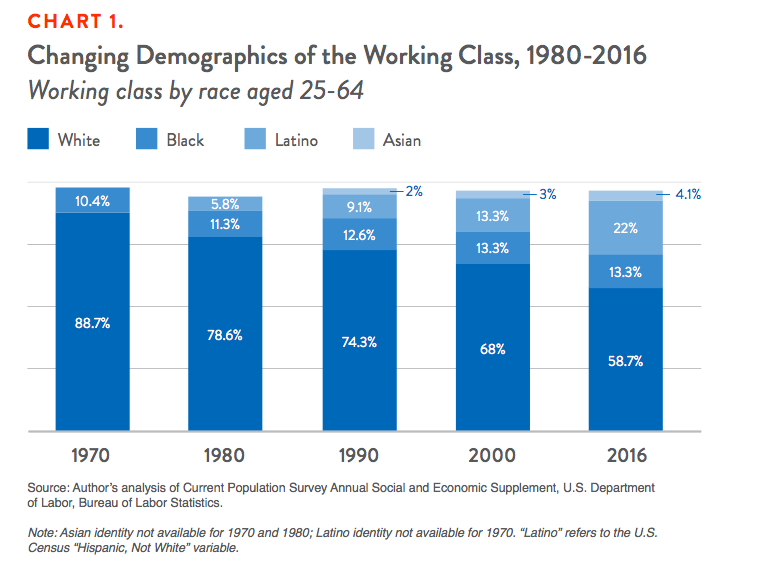

Far too often, the term “working class” is conflated with white and male identities, frequently used as a short-hand to conjure the former archetype of the working class as a white man who works in manufacturing. Of course, the working class has always been more diverse than this stereotype, and that is even more true today (see Chart 1 and Chart 2). As factories shuttered and good jobs for those without college degrees became scarcer, millions more Americans earned bachelor’s and advanced degrees, a process that perversely exacerbated already hardened lines of privilege, with whites earning college degrees at a much greater rate than blacks or Latinos as the cost of college increased substantially over the same time period. As a result, today’s working class is more black and Latino than it was in the industrial era. And it is more female too, as a result of the growing labor force participation of women with children since the 1970s.

As the manufacturing footprint in the working class has shrunk, so has the white male archetype that has historically defined the working class. And as the share of private-sector workers in unions shrank along with those jobs, and working-class jobs became more diffuse and spread across numerous sectors, the idea of a coherent working class has lost its force.

Put simply, the working class shifted from “making stuff” to “serving and caring for people”—a change that carried significant sociological baggage. The long-standing “others” in our society—women and people of color—became a much larger share of the non-college-educated workforce. And their marginalized status in our society carried over into the working class, making it easier to overlook and devalue their work. The racial and gender diversity of today’s working class facilitates its invisibility in two important ways. First, a unifying, single archetype of the new working class remains elusive. Would it be a Latina hotel housekeeper? A black home care worker? A white warehouse worker? An Asian cashier? Definitions want to be neat and tidy, but this working class lacks the defining center of gravity that manufacturing provided the old working class. The second way in which the racial and gender diversity of the new working class undercuts its power is by the very fact that it is so disproportionately black, brown, and female—groups long marginalized in our nation’s political and economic spheres.

- The new working class is more racially diverse than it was decades ago, with more than 41 percent comprising African Americans (13 percent), Latinos (22 percent), and Asian Americans (4 percent). It’s even more diverse if we look at the youngest members of the working class, those aged 25 to 34, with people of color comprising 49 percent of the younger working class. 4

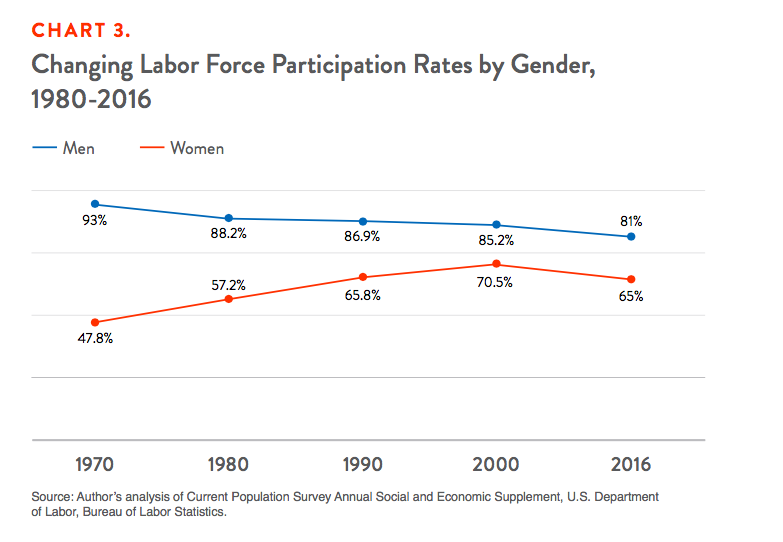

- Today, 2 out of 3 non-college-educated women are in the labor force, up from just over half in 1980 (see Chart 3). Meanwhile, non-college-educated men are in the labor force at a lower rate than they were in 1980, down from 9 out of 10 to 8 out of 10.

As the working class becomes more racially diverse with each passing year, addressing issues of economic insecurity will require addressing how gender and racial inequalities are woven together in the class struggle.

The Jobs of the Working Class

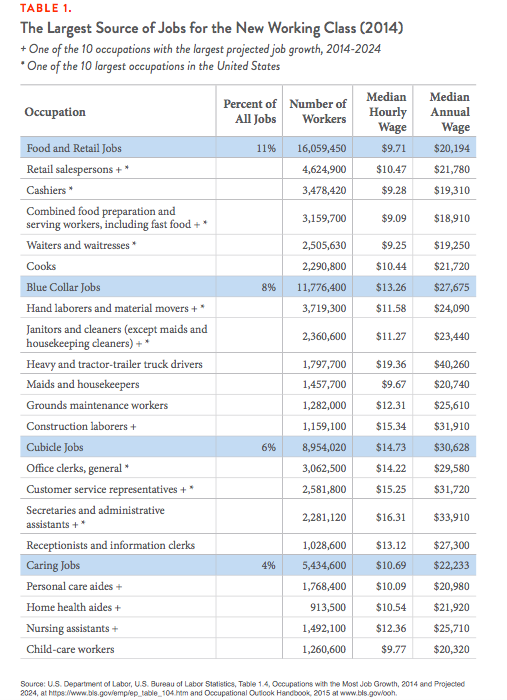

The largest sources of jobs for the new working class fall into 4 main groups: retail and food jobs, blue-collar jobs, cubicle jobs, and caring jobs (see Table 1). Many of these jobs exist at the bottom of a long line of contracts and subcontracts, or are staffed by temp agencies, or are part of a franchise system—all forms of hiring that no longer align with existing labor laws written almost a century ago, making this working class more vulnerable to wage theft, unstable schedules and occupational and safety hazards.

- Only 8 percent of the working class holds jobs in the manufacturing sector, down from about 20 percent in 1980. Today 1 out of 5 working-class employees holds a job in the behemoth retail sector and another 1 out of 5 holds a job in the catchall category of professional and related services, a sector that includes the mushrooming health services occupations. 5 Today’s working-class is centered in the service and caring economy, where robust job growth is expected for the foreseeable future.

- Only 4 out of the 15 occupations that will add the most jobs to our economy in the next decade will require a bachelor’s degree. 6

- The 5 occupations that employ the largest number of workers include only 1 clear middle-class job requiring a bachelor’s degree: registered nurse. The rest of America’s largest occupations are retail salespeople, cashiers, food service and prep workers, and janitors. 7

Food and Retail Jobs

Topping the list of the largest source of jobs for the new working class are food and retail positions, employing over 14 million workers. There’s an enduring image of retail and food workers as being high school or college students who cruise through during summers or work after school year-round but then kiss those jobs goodbye once they’ve earned better credentials. But like most stereotypes, this image is far from accurate. Among waiters and waitresses who are aged 25 to 64, a full 8 out of 10 do not have a college degree. Similarly, most retail salespeople don’t have college degrees either: 75 percent. But what about fast-food workers? Aren’t they mostly teenagers? Nothing epitomizes teen jobs more than flipping burgers or working the drive-through for any of the big fast-food companies. Well, it turns out that just 30 percent of fast-food workers are teenagers. Another 30 percent are aged 20 to 24. The rest—40 percent—are 25 or older. 8 And just over one-quarter of fast-food workers are parents who must rely on meager pay and unstable schedules to provide for their children. 9

The reality of retail workers is also quite different from the stereotype. Over half of retail workers are contributing 50 percent or more to their family’s income. 10 And as in fast food, most of these jobs are held by adults without college degrees—defying the notion of a teen-centered workplace.

The Blue Collar Jobs

In the top-10 list of occupations providing the largest number of jobs in our country, 2 of the 10 (laborers/material movers and janitors) could be described as traditional blue-collar work, that is, physical labor done overwhelmingly by men. But unlike 4 decades ago, these jobs aren’t on the assembly line or factory floor. Today 2 million people in the new working class are employed as janitors or cleaners, earning an average hourly wage of $11.95. 11 Nearly 7 out of 10 of these jobs are held by men. About half of them are held by whites, whereas Latinos make up 30 percent, African Americans 16 percent, and Asian Americans 3 percent of the other half. 12 The other big occupation for working-class men today is what’s known as hand laborers and material movers, employing 3.5 million people. 13 This is classic manual labor: moving freight or stock to and from cargo containers, warehouses, and docks. It also includes sanitation workers, who pick up commercial and residential garbage and recycling. The job requires a lot of strength, because most of the lifting and moving is done by hand, not by a machine.

The Cubicle Jobs

The third largest source of jobs for the working class, coming in at over 7.5 million, breaks into 3 large occupational categories: general office clerks, secretaries and administrative assistants, and customer-service representatives. None of these jobs requires more than a high school diploma, though a fair number of college graduates may find themselves doing this kind of work as a way to get their foot in the door. But by and large, these jobs are held by working-class women. They answer phones, file papers, deal with customer complaints, type memos, make copies, order supplies, and basically keep everything in the office running smoothly. These jobs are found in a wide range of settings, from doctors’ offices to technology companies to local bank branches. In fact, despite the prevalence of ATMs, over a half million people work as bank tellers, with a median pay of $11.99. 14 And like fast-food and retail workers, one-third of bank tellers must rely on public assistance such as food stamps and health insurance programs. 15

The Caring Jobs

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, it was not uncommon for white middle-class families to employ a woman of color to help clean the house, prepare meals, and care for children or elders. The legacy of this occupational segregation remains today: the majority of these caring jobs are still done by women of color, with a disproportionate share held by black women. Black women make up a full one-third of nursing assistants and home health aides and one-fifth of personal care aides (compared to about 6.5 percent of the population). Latinas make up 14 percent of nursing assistants and home health aides and close to 20 percent of personal care aides (compared to about 8.5 percent of the population). Taken together, close to 5 million people in our economy are employed as home health aides, personal aides, nursing assistants, and child-care workers, all earning around $9 or $10 an hour. The number of home-care industry jobs has more than tripled since the 1970s and will continue to be one of the largest sources of new jobs in the coming decades, as the baby boomers continue to age. Similarly, as the Millennial generation hits its peak child-bearing years, the demand for child-care workers is also expected to grow rapidly.

The Wages of the Working Class

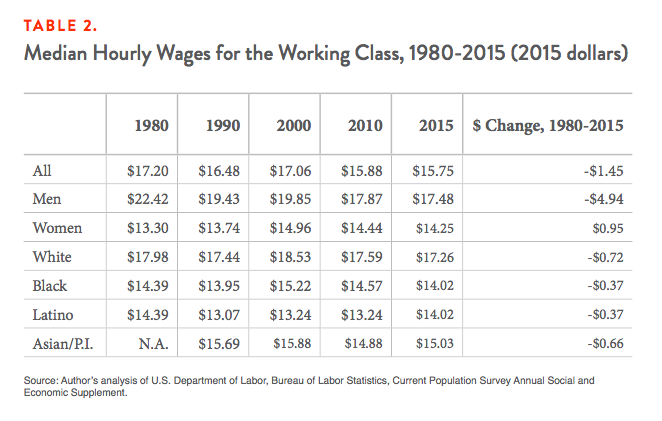

The median hourly wage of today’s working class is $15.75—a full $1.44 less than in 1980, after adjusting for inflation. 16 Today more than one-third of full-time workers earn less than $15 an hour, and fully 47 percent of all workers earn less than $15 an hour. 17 Close to half of workers making less than $15 per hour are over the age of 35. 18 Looking at the working class as an undifferentiated whole hides very important distinctions by gender, race, and age (see Table 2). Like American society more generally, there’s a hierarchy of earnings. Working-class men still out-earn all other demographic groups in the working class, despite a nearly $5 per hour decline in real wages over the past 3 decades. Today the median hourly wage for working-class men is $17.56, down from $22.04 in 1980. The white working class makes significantly more than any other demographic group, thanks in large part to the higher wages of men. As Table 2 shows, hourly wages for most workers have been stagnant over the past 3 decades, with modest increases for women and only significant declines for men.

An examination of wage trends by race and gender shows the reality of an enduring white and male wage premium (See Chart 4). In 2015 white working-class men earned $4.11 more per hour than black working-class men and $4.17 more than Latino working-class men. White working-class women earned $1.94 more than black working-class women and $2.52 more than working-class Latinas. Across all races, working-class men earned more than working-class women. 19

Women and people of color have made great strides in the past 50 years, but there’s no turning away from the reality that our society is still organized along relatively rigid gender and racial hierarchies. As the quality of the new jobs being created in America continues to deteriorate, the inequities by race and gender are further exacerbated.

Nearly twice as many women as men work in jobs paying wages below the poverty line. In fact, 5 of the most common occupations for women—home health aides, cashiers, maids and household cleaners, waitresses, and personal-care aides—fall into that category, compared to just 2 of the most common jobs for men. 20 With the exception of waitresses, these jobs are either primarily or disproportionately done by women of color.

The Politics of the Working Class

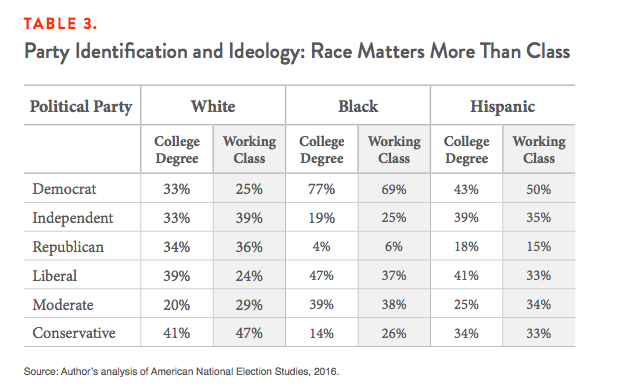

Much has been made of the polarization of American politics, with the conventional split being between Republicans and Democrats. What’s less acknowledged is how much one’s race correlates with being a Republican or a Democrat, a liberal or a conservative. Data from American National Election Studies (ANES), the premier source for public opinion on issues, elections, and political participation, shows substantial differences by race in whether someone considers themselves a Democrat, Republican, or independent—and less significant differences by class. Both blacks and Latinos consider themselves Democrats over Republicans by a very large degree. Working-class blacks are almost 3 times as likely as working-class whites to be Democrats, and working-class Latinos are twice as likely to be Democrats as working-class whites.

Working-Class Political Participation

There is no doubt that the United States has a serious voter turnout problem. Over the past 4 decades, turnout in presidential elections has hovered around 60 percent. In 2016, 61 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot. And among that meager percentage, wealthier and white voters show up in greater numbers than others. In 2016, 48 percent of people with incomes below $30,000 voted, compared to 78 percent of people with incomes above $100,000. And contrary to popular perception, voters with incomes below $30,000 overwhelming cast their ballots for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump, by 53 percent to 40 percent.

Since 1972, the difference in the policy preferences of voters and nonvoters about government’s role in our society have widened, with voters much more aligned with conservative preferences and nonvoters more aligned with progressive policy preferences. Missing voters, who are more likely to be low-income, are more liberal on questions of redistribution in particular, specifically on the need for government to provide jobs, services, and health care.

Politicians focus their campaigns, and all of their polling, on motivating “likely voters” to cast their vote for them. But structural barriers, including burdensome registration procedures, combined with an enthusiasm gap means that the working class is more likely to be missing from the pool of “likely voters.” And so the agenda is set by an electorate that is more white and more affluent than the nation as a whole. This has profound consequences on the types of issues candidates campaign on and what they prioritize once in office. And those decisions have deep implications about the kind of social contract our elected leaders deem appropriate for our country, generation after generation.

Research on turnout and policy outcomes in other countries corroborates the idea that countries with less class bias in voting and higher turnout have more generous social welfare policies. Researchers examining our nation’s depressed levels of voting came to the conclusion that “low turnout offers a potentially compelling explanation why the American welfare state has been so much less responsive to rising market inequality than other welfare states.” A study of 85 democracies found that higher voter turnout leads to higher total revenues, higher government spending, and more generous welfare state spending.

One could conclude from this research that the recent conservative attacks on voting rights, from requiring photo identification to shortening early voting opportunities, both of which dampen turnout among younger, lower-income, and voters of color, are clearly designed to preserve an ideological hegemony that doesn’t reflect the needs of all the people in our democracy.

Who Calls Themselves Working Class?

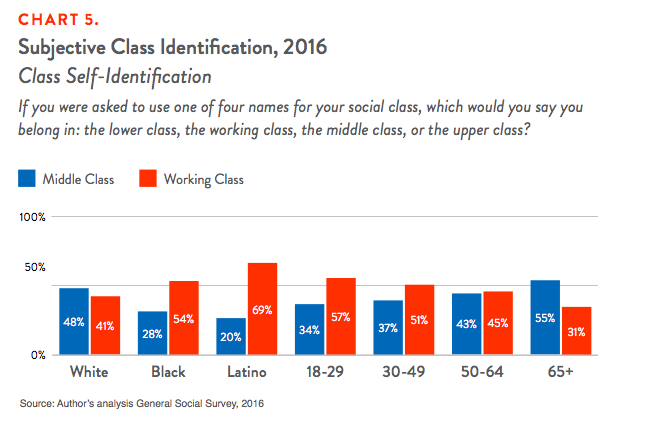

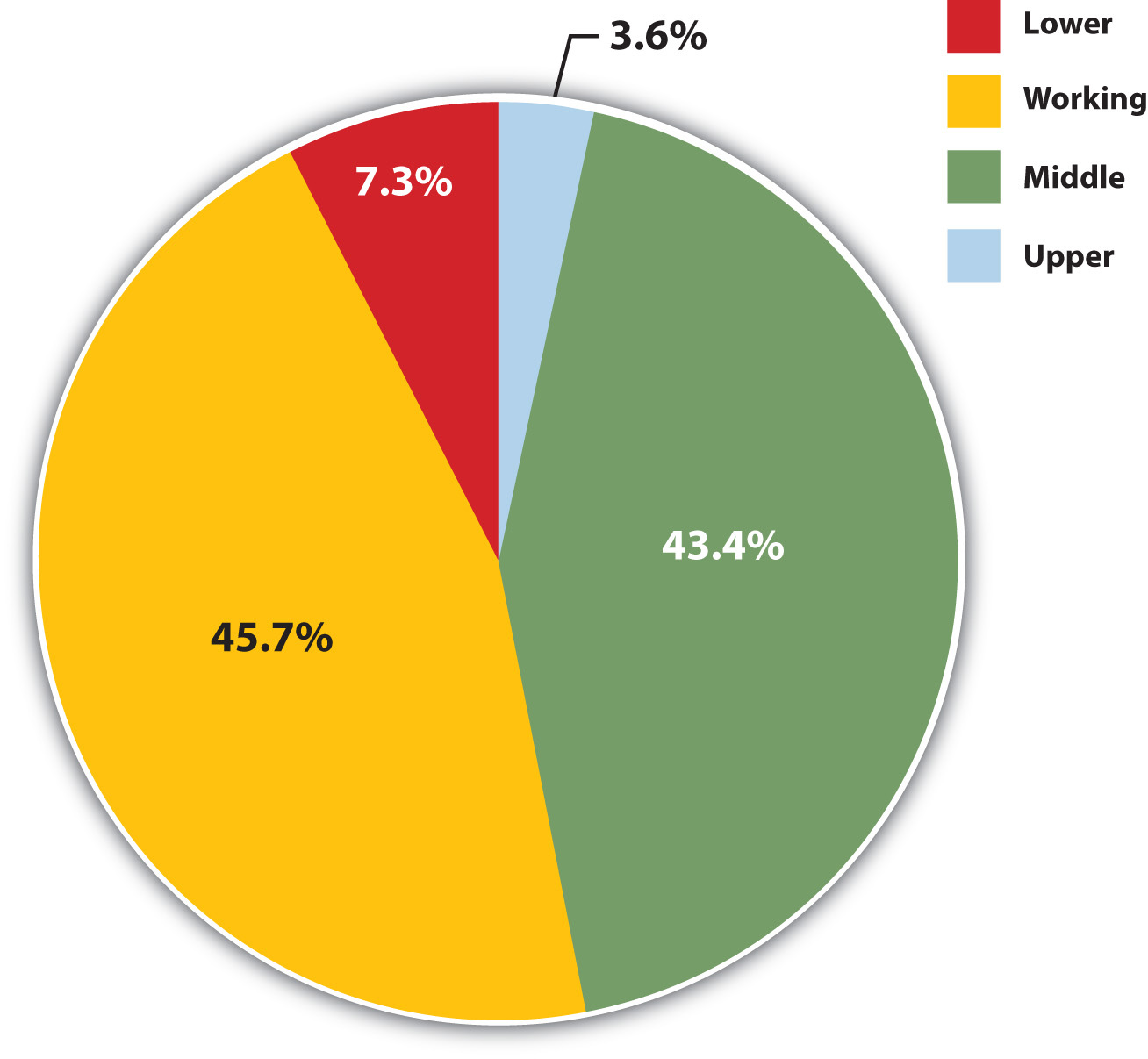

It’s all too common to hear a political pundit say that most Americans identify as middle class. But it isn’t true. Part of the problem is that many polls don’t even include the option of identifying as “working class,” instead offering only upper, middle, and lower class as options. It turns out that when polls offer “working class” as an option, just as many people self-identify as working class as middle class. The General Social Survey, a long-running public opinion survey, found in 2016 that 47 percent of respondents identified themselves as working class, compared to 41 percent who identified themselves as middle class. Interestingly, black and Latino individuals were much more likely than whites to identify as working class (See Chart 5). 21 Seventy percent of Latinos consider themselves working class, compared to 54 percent of blacks and 41 percent of whites. In fact, in every year since the early 1970s, the percentage of Americans who identify as working class has ranged between 44 and 50 percent (See Chart 6).

- 1 Michael Zweig, ed., What’s Class Got to Do with It? American Society in the Twenty-First Century (New York: ILR Books, 2004), p. 4

- 3 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers, 2013,” BLS Reports, March 2014. http://www.bls.gov/cps/minwage2013.pdf.

- 4 Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Data retrieved from IPUMS-CPS: Steven Ruggles et al., Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [machine-readable database] (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010).

- 5 Author’s analysis of 1970–2000 Decennial Census, 2011–2012 U.S. Census American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau Public Use Microdata retrieved from Ruggles et al., Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0.

- 6 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 5. Occupations with the Most Job Growth, 2012 and Projected 2022,” December 19, 2013. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.t05.htm.

- 7 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment and Wages for the Largest and Smallest Occupations, May 2012,” March 29, 2013, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2016/retail-salespersons-and-cashiers-were-....

- 8 Janelle Jones and John Schmitt, Slow Progress for Fast-Food Workers, Center for Economic and Policy Research, August 6, 2013. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/cepr-blog/slow-progress-for-fast-foo....

- 10 The Demographics of the Retail Work Force, Demos, November, 18, 2012. http://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/data_bytes/demographics.png.

- 11 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Data Tables for Overview of May 2012 Occupational Employment and Wages,” March 29, 2013. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ocwage.pdf.

- 12 Independent analysis of U.S. Census 2012 and 2011 American Community Survey. Data retrieved from IPUMS-USA: Steven Ruggles et al., Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database] (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010).

- 13 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Data Tables for Overview of May 2012 Occupational Employment and Wages.”

- 14 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2014–15, Tellers. http://www.bls.gov/ooh/office-and-administrative-support/tellers.htm.

- 15 Sylvia Allegretto et al., The Public Cost of Low-Wage Jobs in the Banking Industry, UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, October 2014. http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/the-public-cost-of-low-wage-jobs-in-the-....

- 16 Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

- 17 Ben Henry and Allyson Fredericksen, Equity in the Balance: How a Living Wage Could Help Women and People of Color Make Ends Meet,” The Job Gap, November 2014. https://jobgap2013.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/2014jobgapequity1.pdf.

- 18 Irene Tung, Yannet Lathrop, and Paul Sonn, The Growing Movement for $15, National Employment Law Project, April 2015. http://nelp.org/content/uploads/Growing-Movement-for-15-Dollars.pdf.

- 19 Author’s analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Data retrieved from IPUMS-CPS: Steven Ruggles et al., Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010.

- 20 Institute for Women’s Policy Research, The Gender Wage Gap.

- 21 Author’s analysis of General Social Surveys, 1972-2014 [machine-readable data file]. Principal Investigator, Tom W. Smith; Co-Principal Investigator, Peter V. Marsden; Co-Principal Investigator, Michael Hout; Sponsored by National Science Foundation.—NORC ed.— Chicago: NORC at the University of Chicago [producer]; Storrs, CT: The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut.

Join our email list

Stay updated on the fight for racial equity, an inclusive democracy, and an economy free of barriers.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Personal Finance

Working Class Explained: Definition, Compensation, Job Examples

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wk_headshot_aug_2018_02__william_kenton-5bfc261446e0fb005118afc9.jpg)

Morsa Images / Getty Images

What Is the Working Class?

"Working class" is a socioeconomic term used to describe persons in a social class marked by jobs that provide low pay, require limited skill, or physical labor. Typically, working-class jobs have reduced education requirements. Unemployed persons or those supported by a social welfare program are often included in the working class.

Key Takeaways

- Working class is a socioeconomic term describing persons in a social class marked by jobs that provide low pay and require limited skill.

- Typically, working-class jobs have reduced education requirements.

- Today, most working-class jobs are found in the services sector and include clerical, retail sales, and low-skill manual labor vocations.

Understanding the Working Class

While "working class" is typically associated with manual labor and limited education, blue collar workers are vital to every economy. Economists in the United States generally define "working class" as adults without a college degree. Many members of the working class are also defined as middle-class.

Sociologists such as Dennis Gilbert and Joseph Kahl, who was a sociology professor at Cornell University and the author of the 1957 textbook The American Class Structure, identified the working class as the most populous class in America.

Other sociologists such as William Thompson, Joseph Hickey and James Henslin say the lower middle class is largest. In the class models devised by these sociologists, the working class comprises between 30% to 35% of the population, roughly the same number in the lower middle class. According to Dennis Gilbert, the working class comprises those between the 25th and 55th percentile of society.

Karl Marx described the working class as the "proletariat", and that it was the working class who ultimately created the goods and provided the services that created a society's wealth. Marxists and socialists define the working class as those who have nothing to sell but their labor-power and skills. In that sense, the working class includes both white and blue-collar workers , manual and menial workers of all types, excluding only individuals who derive their income from business ownership and the labor of others.

Types of Working Class Jobs

Working-class jobs today are quite different than the working-class jobs in the 1950s and 1960s. Americans working in factories and industrial jobs have been on the decline for many years. Today, most working-class jobs are found in the services sector and typically include:

- Clerical jobs

- Food industry positions

- Retail sales

- Low-skill manual labor vocations

- Low-level white-collar workers

Oftentimes working-class jobs pay less than $15 per hour, and some of those jobs do not include health benefits. In America, the demographics surrounding the working-class population is becoming more diverse. Approximately 59% of the working-class population is comprised of white Americans, down from 88% in the 1940s. African-Americans account for 14% while Hispanics currently represent 21% of the working class in the U.S.

History of the Working Class in Europe

In feudal Europe, most were part of the laboring class; a group made up of different professions, trades, and occupations. A lawyer, craftsman, and peasant, for example, were all members–neither members of the aristocracy or religious elite. Similar hierarchies existed outside Europe in other pre-industrial societies.

The social position of these laboring classes was viewed as ordained by natural law and common religious belief. Peasants challenged this perception during the German Peasants' War. In the late 18th century, under the influence of the Enlightenment, a changing Europe could not be reconciled with the idea of a changeless god-created social order. Wealthy members of societies at that time tried to keep the working class subdued, claiming moral and ethical superiority.

Joseph Kahl. " The American Class Structure ." Rinehart, 1957.

Center for American Progress Action Fund. " What Everyone Should Know About America’s Diverse Working Class ." Accessed Sep. 3, 2020.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-90370650-601046c512ed4aedbc686844dcfd6a52.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is the Working Class?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/201910066790745134093933335-ff6c2e8b11c3439186f2bf827fb07b85.jpeg)

Definition and Examples of Working Class

How does the working class work, diversity in the working class, criticism of the working class, what it means for working-class workers.

Reza Estakhrian / Getty Images

“ Working class ” typically refers to a subsection of the labor force that works in the service or industrial sectors and does not hold a four-year college degree.

Key Takeaways

- While there is no universal definition of “working class,” the term commonly refers to workers in the service sector who hold less than a four-year college degree.

- Historically predominately white and male, the U.S. working class has become increasingly diverse in recent decades.

- Some common challenges the working class may face include wage stagnation, declining worker power, and meeting the rising cost of living.

The term “working class” often typically describes members of the labor force that hold a service-type occupation and do not hold a bachelor’s degree. Common working class occupations include restaurant employees, auto mechanics, construction workers, and other service-type workers.

- Alternate name : Blue-collar workers

Defining the working class is highly subjective and can vary by the analyst. Common indicators of membership in the working class include certain levels of annual household income, net worth, and education.

For example, let’s say a researcher classifies working-class workers as those who do not hold a college degree and are between the ages of 18 and 64 years old. Sally, who is 33 years old, works as a grocery store clerk, and did not go to college would be considered a member of the working class.

Many analysts use education level as an indicator of membership in the working class since educational credentials typically do not fluctuate as frequently as income .

For example, two employees may have the same degree and hold the same position within a company. However, one employee may not identify as working class because they have worked for the company for 10 years and make 50% more than the other employee.

Researchers rely on other indicators, such as net worth, the type of job, or how much autonomy an individual holds in their job position, as well.

Generally, the working class works jobs in food and retail, blue-collar work, caregiving, or some type of cubicle position. Some common examples of working-class occupations can include:

- Factory workers

- Restaurant workers

- Nursing home staff

- Automotive professionals

- Delivery services

In 2015, the retail industry employed more working-class adults than the manufacturing, minor, and construction industries combined. That same year, the health care industry also experienced a notable increase in working-class jobs.

The racial diversity makeup of the working class has evolved over the years. Around the 1940s, white workers comprised 88% of the working-class labor force. In 2015, this figure dropped to 58.9%, while African Americans and Hispanic Americans made up 13.7% and 20.9% of the working-class labor force respectively. The number of working-class women also increased, comprising 45.6% of the working class in 2015—it was less than 30% in 1940.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that the working class, ages 18 to 64 years old, will become the majority people of color by 2032.

As mentioned, there is no universal definition of the working class. Since education, income, occupation, and other factors can vary by the individual, it can be difficult to accurately measure the size and characteristics of the working class.

Some say retirement can skew the data if the analyst uses education as a working class indicator. A retired American, for example, may have not held a four-year college degree but do not identify as working class because they are not actually working.

Some analysts may still consider those who do not hold college degrees and are unemployed as part of the working class.

In some cases, researchers may choose to avoid using the term “working class” altogether and instead classify individuals by lower, middle, and upper class.

Working-class workers between the ages of 25 and 54, on average, are more likely to report a concern regarding their financial situation.

Some say wage stagnation is a significant factor that affects the financial health of working-class workers, who may not share in the wealth they generate. The rising cost of living exacerbates these financial concerns among working-class workers.

Some organizations advocate for laws that increase working power by making it easier to unionize in an effort to increase the quality of industrial jobs. More full employment opportunities, increased public employment, and apprenticeships can potentially also ease the struggles of the working class.

Economic Policy Institute. " People of Color Will be a Majority of the American Working Class in 2032 ." Accessed Nov. 29, 2021.

Center for American Progress Action Fund. " What Everyone Should Know About America’s Diverse Working Class ." Nov. 29, 2021.

Demos. " Understanding the Working Class ." Accessed Nov. 29, 2021.

Class Matters. " Working Definitions ." Accessed Nov. 29, 2021.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Proletariat (Working Class)

Introduction, general overviews.

- Classic Works

- Data Sources

- Formation and History

- Deindustrialization

- Mobilization and Unions

- Culture and Education

- Globalization

- Less Developed Countries

- Measurement

- Working-Class Studies

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Economic Sociology

- Social History

- Social Stratification

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Global Racial Formations

- Transition to Parenthood in the Life Course

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Proletariat (Working Class) by Yunus Kaya LAST REVIEWED: 20 September 2012 LAST MODIFIED: 20 September 2012 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0089

The prevalence of wage labor has been a defining characteristic of modern societies. Following the Industrial Revolution, the people who sold their labor for survival in the newly emerging modern societies were usually labeled as the “working class” or the “proletariat.” Originally used by Romans to label citizens with very little or no property, the term “proletariat” was adopted by Karl Marx to categorize the working class in the newly industrialized European societies, and since then the two terms have been used interchangeably. The initial dominance of industrial work made the working class synonymous with manual work. However, as service-sector employment expanded and the number of people employed in white-collar occupations increased, the definition of “working class” also changed. Today, although there are serious debates and disagreements about the definition of “working class,” or even its very existence, many scholars define the term as comprising people who earn their living through wage labor, who do not own any assets or capital, and who do not possess workplace authority. Over the years, scholars have argued that working classes differ from the rest of the societies they belong to with their politics, culture, family structures, and the conditions they live in. However, it is also not possible to talk about a single and unified working class in any society, as working classes are divided through the lines of gender, race, and ethnicity. Today, working classes all over the world are struggling with the challenges of globalization and new technologies, although the specific challenges they face differ in developed and less developed countries.

Although it is hard to find comprehensive reviews or introductory texts on the working class, a few studies provide insights into the literature on the working class, and they shed light on the contemporary issues and challenges faced by the working classes. For example, Wright 2005 reviews major theoretical approaches to social class in general and the working class in particular. Roberts 1990 compares the literatures on proletariat and peasants and provides a comprehensive review of the literature until 1990. Arnesen 2007 ; Zweig 2012 ; and Mishel, et al. 2009 draw a compelling picture of working-class Americans and the various challenges they face. Bourdieu, et al. 1999 includes analyses of various aspects of the French working class, while Perrucci and Perrucci 2007 debates various effects of the new technologies and the global economy.

Arnesen, Eric, ed. 2007. Encyclopedia of U.S. labor and working-class history . 3 vols. New York: Routledge.

These volumes include more than 650 entries that cover the history of the American working class from the colonial era to the present. They contain articles on a vast number of issues, such as race and ethnicity, gender, slavery, regions, occupations, working-class culture, labor unions, and resistance.

Bourdieu, Pierre, et al. 1999. The weight of the world: Social suffering in contemporary society . Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

Although this is not strictly an analysis of the working class, it reviews and discusses many problems and challenges faced by the working class in France. The authors who contributed to this volume discuss many issues, including racism and discrimination, working-class culture, religion, deindustrialization, and social exclusion. Originally published in 1993 as La misère du monde (Paris: Seuil).

Mishel, Lawrence, Jared Bernstein, and Heidi Shierholz. 2009. The state of working America: 2008–2009 . Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.

This work is the latest edition of The State of Working America , which has been published biannually by the Economic Policy Institute since 1988. Each volume includes an updated review of issues that are faced by working-class Americans and their families. It provides a comprehensive coverage of variety of issues, such as wages, education, health, and inequality.

Perrucci, Robert, and Carolyn C. Perrucci, eds. 2007. The transformation of work in the new economy: Sociological readings . Los Angeles: Roxbury.

A very helpful source book and comprehensive reader on the new economy and the contemporary challenges faced by all working people, including working classes. The reader is divided into five sections: “Historical Background for the New Economy,” “How Globalization, Technology, and Organization Affect Work,” “The Changing Face of Work,” “Work and Family Connections,” and “Emerging Issues.” Can be used in upper-level undergraduate or graduate courses.

Roberts, Bryan R. 1990. Peasants and proletarians. Annual Review of Sociology 16:353–377.

DOI: 10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.002033

As an Annual Review article, it provides a comprehensive survey of the literature on the working class. It compares peasants and proletarians with regard to differences between them in political action, social structure, and demographic behavior, and discusses the effects of contemporary changes in economies and labor markets. Also includes references to various important works in the literature.

Wright, Erik Olin, ed. 2005. Approaches to class analysis . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511488900

This edited volume comprises six essays on different theoretical approaches to class analysis, as well as a review essay by the editor. It is a good overview of the different theories in the field, and it can be very helpful in an upper-level undergraduate or a graduate class.

Zweig, Michael. 2012. The working class majority: America’s best kept secret . 2d ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.

A comprehensive and sometimes provocative account of the working class in the United States. It emphasizes the importance of the social class in understanding the social structure and work life in the United States. It discusses many issues, including the underclass, globalization, family, and the role of government. It also includes a useful section labeled “Working Class Resource Guide.”

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Sociology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Actor-Network Theory

- Adolescence

- African Americans

- African Societies

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Analysis, Spatial

- Analysis, World-Systems

- Anomie and Strain Theory

- Arab Spring, Mobilization, and Contentious Politics in the...

- Asian Americans

- Assimilation

- Authority and Work

- Bell, Daniel

- Biosociology

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Catholicism

- Causal Inference

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Society

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights

- Civil Society

- Cognitive Sociology

- Cohort Analysis

- Collective Efficacy

- Collective Memory

- Comparative Historical Sociology

- Comte, Auguste

- Conflict Theory

- Conservatism

- Consumer Credit and Debt

- Consumer Culture

- Consumption

- Contemporary Family Issues

- Contingent Work

- Conversation Analysis

- Corrections

- Cosmopolitanism

- Crime, Cities and

- Cultural Capital

- Cultural Classification and Codes

- Cultural Economy

- Cultural Omnivorousness

- Cultural Production and Circulation

- Culture and Networks

- Culture, Sociology of

- Development

- Discrimination

- Doing Gender

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Durkheim, Émile

- Economic Globalization

- Economic Institutions and Institutional Change

- Education and Health

- Education Policy in the United States

- Educational Policy and Race

- Empires and Colonialism

- Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Sociology

- Epistemology

- Ethnic Enclaves

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

- Exchange Theory

- Families, Postmodern

- Family Policies

- Feminist Theory

- Field, Bourdieu's Concept of

- Forced Migration

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Gender and Bodies

- Gender and Crime

- Gender and Education

- Gender and Health

- Gender and Incarceration

- Gender and Professions

- Gender and Social Movements

- Gender and Work

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender, Sexuality, and Migration

- Gender Stratification

- Gender, Welfare Policy and

- Gendered Sexuality

- Gentrification

- Gerontology

- Global Inequalities

- Globalization and Labor

- Goffman, Erving

- Historic Preservation

- Human Trafficking

- Immigration

- Indian Society, Contemporary

- Institutions

- Intellectuals

- Intersectionalities

- Interview Methodology

- Job Quality

- Knowledge, Critical Sociology of

- Labor Markets

- Latino/Latina Studies

- Law and Society

- Law, Sociology of

- LGBT Parenting and Family Formation

- LGBT Social Movements

- Life Course

- Lipset, S.M.

- Markets, Conventions and Categories in

- Marriage and Divorce

- Marxist Sociology

- Masculinity

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral...

- Material Culture

- Mathematical Sociology

- Medical Sociology

- Mental Illness

- Methodological Individualism

- Middle Classes

- Military Sociology

- Money and Credit

- Multiculturalism

- Multilevel Models

- Multiracial, Mixed-Race, and Biracial Identities

- Nationalism

- Non-normative Sexuality Studies

- Occupations and Professions

- Organizations

- Panel Studies

- Parsons, Talcott

- Political Culture

- Political Economy

- Political Sociology

- Popular Culture

- Proletariat (Working Class)

- Protestantism

- Public Opinion

- Public Space

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- Race and Sexuality

- Race and Violence

- Race and Youth

- Race in Global Perspective

- Race, Organizations, and Movements

- Rational Choice

- Relationships

- Religion and the Public Sphere

- Residential Segregation

- Revolutions

- Role Theory

- Rural Sociology

- Scientific Networks

- Secularization

- Sequence Analysis

- Sex versus Gender

- Sexual Identity

- Sexualities

- Sexuality Across the Life Course

- Simmel, Georg

- Single Parents in Context

- Small Cities

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Closure

- Social Construction of Crime

- Social Control

- Social Darwinism

- Social Disorganization Theory

- Social Epidemiology

- Social Indicators

- Social Mobility

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Networks

- Social Policy

- Social Problems

- Social Psychology

- Social Theory

- Socialization, Sociological Perspectives on

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociological Approaches to Character

- Sociological Research on the Chinese Society

- Sociological Research, Qualitative Methods in

- Sociological Research, Quantitative Methods in

- Sociology, History of

- Sociology of Manners

- Sociology of Music

- Sociology of War, The

- Suburbanism

- Survey Methods

- Symbolic Boundaries

- Symbolic Interactionism

- The Division of Labor after Durkheim

- Tilly, Charles

- Time Use and Childcare

- Time Use and Time Diary Research

- Tourism, Sociology of

- Transnational Adoption

- Unions and Inequality

- Urban Ethnography

- Urban Growth Machine

- Urban Inequality in the United States

- Veblen, Thorstein

- Visual Arts, Music, and Aesthetic Experience

- Wallerstein, Immanuel

- Welfare, Race, and the American Imagination

- Welfare States

- Women’s Employment and Economic Inequality Between Househo...

- Work and Employment, Sociology of

- Work/Life Balance

- Workplace Flexibility

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What So Many People Don’t Get About the U.S. Working Class

- Joan C. Williams

The reasons for Trump’s win are obvious, if you know where to look.

Pundits and political analysts point to the white working class (WWC) as the voting bloc that tipped the 2016 Presidential Election in Donald Trump’s favor. Did Trump know something about this group that progressives and members of the Republican establishment were not privy to? No, says Joan C. Williams, but he was able to appeal to their values such as straight talk, masculinity, and economic independence, in a way that experienced politicians didn’t consider. Class politics drove the 2016 election, and it was cluelessness about the needs of the WWC that drove Trump’s victory. If Democrats want to connect with this group, they need to consider how economics, geography, and the WWC’s relationship with the classes adjacent to them—the poor and white collar workers—influence their values. Not doing so poses additional risk in an already unpredictable political climate.

My father-in-law grew up eating blood soup. He hated it, whether because of the taste or the humiliation, I never knew. His alcoholic father regularly drank up the family wage, and the family was often short on food money. They were evicted from apartment after apartment.

- Joan C. Williams is a Sullivan Professor of Law at University of California College of the Law, San Francisco and the founding director of Equality Action Center. An expert on social inequality, she is the author of 12 books, including Bias Interrupted: Creating Inclusion for Real and for Good (Harvard Business Review Press, 2021) and White Working Class: Overcoming Class Cluelessness in America (Harvard Business Review Press, 2019). To learn about her evidence-based, metrics-driven approach to eradicating implicit bias in the workplace, visit www.biasinterrupters.org .

Partner Center

Center for American Progress

What Policymakers Need To Know About Today’s Working Class

The working class works primarily in service-sector jobs and is more racially and ethnically diverse than ever.

Building an Economy for All, Economy, Middle-Class Economics, Raising Working Standards, Worker Rights, Workforce Development +3 More

Media Contact

Sarah nadeau.

Associate Director, Media Relations

[email protected]

Government Affairs

Madeline shepherd.

Senior Director, Government Affairs

In this article

Today’s working class is far different than the working class of more than half a century ago, at the height of American manufacturing’s importance in the labor market. 1 Yet widespread misconceptions persist about the people without a four-year college degree who make up the American working class. Throughout the 2016 and 2020 election cycles, the term became, in some circles, nearly synonymous with white workers in manufacturing or skilled trades. 2 A new Center for American Progress analysis reveals that, in fact, today’s working class is more diverse than ever.

According to data from the 2021 American Community Survey (ACS), the current working class largely works in services, particularly retail, health care, food service and accommodation, and building services, though manufacturing and construction remain large employers as well. Black, Hispanic, and other workers of color make up 45 percent of the working class, while non-Hispanic white workers comprise the remaining 55 percent. Nearly half of the working class is women, and 8 percent have disabilities.

These statistics highlight the need for policies to address the challenges that the working class faces in 2023.

The major industrial policies that President Joe Biden has signed into law—the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), and the CHIPS and Science Act—will help provide millions of quality jobs to people without college degrees, as well as help far more women and people of color enter construction and manufacturing jobs. 3 These are vital steps. Yet these policies will need to be properly implemented to ensure they deliver high job quality and access to these jobs for workers from all walks of life. Further, additional policies will be required to more broadly improve working conditions in the service sector.

Pro-worker policymakers must understand the diversity of today’s working class as they craft policies to build an economy that truly works for all workers.

Stay informed on Inclusive Economy

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Defining the working class

This analysis defines the working class as comprising labor force participants who do not have a four-year college degree. It refers to non-working-class respondents as “college-educated,” defining them as individuals in the labor force with at least a four-year college degree or higher levels of education. Income can also be used as a measure of class membership, but it is far more variable by respondents’ age and job status than is education. For more details on the approach used in this analysis, see the Methodology section at the end of this brief.

Some surveys and press accounts rely on self-reported status of class membership, but individual attitudes on this topic are shaped by a number of factors and even change over time. A 2022 Gallup poll found that 46 percent of American adults identified as either “working” or “lower” class, with the rest identifying as “upper,” “upper-middle,” or “middle” class. 4

The majority of America's workers are part of the working class

Prior to the 1990s, the working class constituted more than 90 percent of the labor force. Yet even as rates of college education increased, the working class continued to represent the largest portion of the workforce. 5 In 2021, the working class still made up a majority of the American workforce, totaling 104 million workers. This means that, excluding students and active military members, 62 percent of the adult labor force is made up of members of the working class, while 38 percent of the labor force has at least a four-year college degree. (see Figure 1)

These numbers mean that policies directed toward the working class have an outsize impact on the health of the economy.

The working class is more racially and ethnically diverse than ever

For half a century, the working class has been growing more racially and ethnically diverse, and today, workers of color make up 45 percent of it, while non-Hispanic white workers make up the remaining 55 percent. 6 (see Figure 2) The racial and ethnic diversity of today’s working class, even greater than the Center for American Progress Action Fund found in its 2017 analysis of working class demographics using 2015 data, is the product of a decadeslong shift; in 1970, when the share of people of color in the working class began to accelerate, non-Hispanic white workers made up 85 percent of the working class. 7 This trend is poised to continue, with estimates suggesting that workers of color will make up a majority of the working class in 2032—a full 11 years before the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that people of color will constitute more than 50 percent of the entire population of the United States. 8

Furthermore, as shown in Figure 2, the college-educated labor force is disproportionately white, while Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino workers make up a much larger share of the working class. This is in part the product of decades of discriminatory practices in access to education. 9 Indeed, the growing share of Americans of color among the working class comes as a product of two things: 1) the nationwide gaps in degree attainment between white workers and workers of color 10 and 2) the country itself growing more racially and ethnically diverse, especially as Generation Z, the country’s most racially and ethnically diverse generation, 11 continues to enter the labor force. Immigrants of color currently make up 16.9 percent of the working class. 12

Women make up nearly half of the working class

As shown in Figure 3, women make up 44 percent of the working class. This share has remained relatively consistent for several decades: The 2017 CAP Action analysis found that it had been stable at around 46 percent since roughly the 1990s. 13 The proportion of women in the working class is affected not only by the rate at which women earn college degrees, which has been increasing, 14 but also by women’s labor force participation rate. The COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the number of working-class women in the labor force: Although the overall labor force participation rate for women remains roughly the same as in 2019, the total number of working-class women fell from 42.0 million in 2019 to 40.4 million in 2021. 15 Women have borne especially steep job losses and increased caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic, 16 which contributed to working-class women making a disproportionately high number of exits from the labor market. 17 Occupational segregation, meanwhile, has contributed to fewer women reentering the labor market during the nation’s economic recovery. 18

Decrease in working-class women in the labor force, 2019–2021

Additionally, a divide exists between the jobs held by women and men in the working class. Though jobs in the manufacturing and construction sectors make up 10 percent and 12 percent, respectively, of the jobs that working-class people hold, only 8 percent of working-class women are employed in manufacturing, and only 2 percent are employed in construction. Far too often, women in these male-dominated roles still face harassment on the job. 19 Job quality measures that only target manufacturing or construction work, therefore, are insufficient for addressing the needs of women working in service roles, while policymakers nationwide tasked with implementing industrial policies such as the IIJA or the CHIPS and Science Act must ensure the construction and manufacturing jobs those laws create are accessible to women.

Learn more about occupational segregation

Occupational Segregation in America

Mar 29, 2022

Marina Zhavoronkova , Rose Khattar , Mathew Brady

Workers with disabilities are highly represented among the working class

Workers with disabilities make up a larger proportion of the working class than they do the proportion of workers with college degrees. As shown in Figure 4, a total of 8.7 percent of the American working-class labor force has a disability, compared with 4.76 percent of the labor force with four-year college degrees. This represents an increase from 2019, when 7.8 percent of the working class reported having a disability, and is potentially due in part to the disabling effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. 20

According to CAP analysis, 8 million working-class Americans describing themselves as having a disability. (see Methodology) policymakers must ensure that industrial policies create jobs that are accessible to disabled workers. Workers with disabilities already face occupational segregation and other inequities in the workforce and are concentrated in low-paying occupations such as janitors, building cleaners, and personal care aides. 21 So industrial policies must not only raise standards in the industries where disabled workers are currently employed, but also incorporate protections, expand routes to entry, and boost retention for disabled workers in all sectors, while improving access to good jobs. Otherwise, policymakers risk leaving disabled workers behind both in the workforce and on the job. 22

Learn more about the disabling impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 Likely Resulted in 1.2 Million More Disabled People by the End of 2021—Workplaces and Policy Will Need to Adapt

Feb 9, 2022

Lily Roberts , Mia Ives-Rublee , Rose Khattar

Working-class people are more likely to work in retail or to hold service, construction, and manufacturing jobs

Working-class Americans primarily work in different occupations and industries than workers with college degrees. Figure 5 compares the top 10 occupations and industries with the largest numbers of working-class people with the top 10 occupations and industries with the largest numbers of workers who have at least a four-year college degree. Although some industries—especially construction and elementary and secondary school education—are common among both working-class and college-educated workers, members of the working class are far more likely to be employed in retail, accommodation and food service, material moving and truck driving, and building cleaning or other service roles; even in construction, they largely work as laborers. Additionally, home health aides and personal care aides together constitute one of the largest working-class labor forces in the country—more than 1.6 million workers. 23 Overall, the dominance of service-sector roles in the working class has been increasing for decades—with some slowdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic—and will likely only increase in the future. 24

The jobs held by working-class Americans far too often offer low pay, few protections, and insufficient worker voice on the job. Nonunion construction 25 and manufacturing 26 jobs are often low-paying, while other jobs predominant among members of the working class—including in the service sector, 27 food service, 28 health care, 29 retail, 30 and home care 31 —commonly offer low wages, few benefits, and insufficient worker protections. These problems are widespread: While only 17 percent of workers with four-year degrees lack health insurance through their employer or labor union, 37 percent of workers in the working class lack such insurance. Lower job quality worsens economic disparities for the disproportionate numbers of people of color and people with disabilities in the working class, with corresponding impacts on health. 32

Making industrial policy work for the working class

Improving job quality across a wide range of sectors and occupations—including health care, retail, food, and building services, as well construction and manufacturing—is critical to the well-being of the working class.

Although Biden’s signature industrial policy laws include important features to advance job quality for the working class and will create thousands of manufacturing and construction jobs, they need to be properly implemented. Proper implementation will require, among other things, thorough screening of bidders for government projects to ensure capacity and commitment to adopt high-road standards; sufficient agency funding and oversight to monitor and enforce these standards; and empowered community and worker organizations through legally enforceable partnerships, such as community workforce agreements 33 that hold accountable state and local government and private sector recipients. 34

To more broadly enhance job quality and worker power in the service sector, policymakers must go further. This includes passing policies targeted toward specific service-sector occupations, such as proposals to raise standards for home care 35 and child care 36 workers; enacting measures to improve job quality for airport service workers; 37 and expanding to other states the recent California law that aims to improve working conditions in fast food. 38 It also includes supporting policies that increase worker power and raise job quality across the entire economy, such as the Protecting the Right to Organize Act and increases to the minimum wage. 39

The working class today, as ever, is the cornerstone of the American economy, making up a large majority of the workforce yet largely concentrated in lower-paying jobs in the service, retail, and construction sectors. Policies that improve job quality for these workers, and make good jobs accessible to women, workers of color, and workers with disabilities, will therefore bring the greatest benefits to working families. The Biden administration has already taken significant steps forward through the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the IIJA, and the CHIPS and Science Act—three landmark laws that will create quality jobs in American manufacturing and construction. Nevertheless, the share of the working class employed in manufacturing will remain small compared with the share who work in services, and working families are in dire need of policies that set strong standards and empower workers in these occupations. Many policymakers claim to be champions of the working class, but those truly interested in helping must understand this group as it exists and works today in order to ensure all Americans have access to decent, family-supporting jobs.

Methodology

The author relied on 2021 American Community Survey data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau and published by IPUMS-USA. This includes data on demographics, education, and job classifications and allows for an analysis representative of the U.S. population. 40

The author defines a “working-class” person as a member of the labor force—whether currently employed or looking for work—who does not have a four-year college degree. In this analysis, non-working-class respondents are defined as individuals in the labor force with at least a four-year college degree or higher levels of education and are referred to as “college-educated.” The data set was restricted to omit individuals identified as students or members of the military.

One question on the ACS asks respondents to describe whether they are of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin; a second question that lacks these options prompts respondents to indicate their race. As a result, an individual can identify as both Hispanic or Latino as well as a member of any other racial or ethnic group. For this analysis, the author refers to respondents as Hispanic or Latino if they stated that they are of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin in the first question. In the rest of the racial or ethnic groups—white, Black or African American, and other or multiple race—the author included only non-Hispanic respondents to avoid double-counting some respondents.

Disability status was determined from a set of six questions regarding different forms of difficulty because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, including cognitive, physical activity, independent living, self-care, vision, or hearing difficulty. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, “Respondents who report anyone of the six disability types are considered to have a disability.” 41 Throughout this analysis, the author refers to these respondents as “workers with a disability” or “disabled workers.”

- Alex Rowell, “What Everyone Should Know About America’s Diverse Working Class” (Washington: Center for American Progress Action Fund, 2017), available at https://www.americanprogressaction.org/article/everyone-know-americas-diverse-working-class/ .

- Susan Davis, “Top Republicans Work To Rebrand GOP As Party Of Working Class,” NPR, April 13, 2021, available at https://www.npr.org/2021/04/13/986549868/top-republicans-work-to-rebrand-gop-as-party-of-working-class .

- Aurelia Glass and Karla Walter, “How Biden’s American-Style Industrial Policy Will Create Quality Jobs,” Center for American Progress, October 27, 2022, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-bidens-american-style-industrial-policy-will-create-quality-jobs/ .

- Jeffrey M. Jones, “Middle-Class Identification Steady in U.S.,” Gallup, May 19, 2022, available at https://news.gallup.com/poll/392708/middle-class-identification-steady.aspx .

- Based on the author’s analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data also published by IPUMS-USA. Steven Ruggles and others, “Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Version 12.0, U.S. Census Data for Social, Economic, and Health Research, 2021 American Community Survey” (Minneapolis: Minnesota Population Center, 2022), available at https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V12.0 .

- For this analysis, “Hispanic or Latino” workers include all workers who identify as Hispanic or Latino regardless of race; as a result, “white workers” includes only non-Hispanic white workers. For more details on how this analysis differentiates racial and ethnic identities, see the Methodology.

- Rowell, “What Everyone Should Know About America’s Diverse Working Class.”

- Valerie Wilson, “People of color will be a majority of the American working class in 2032” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2016), available at https://www.epi.org/publication/the-changing-demographics-of-americas-working-class/ .

- Marcella Bombardieri, “What the Biden Administration Can Do Now To Make College More Affordable, Accountable, and Racially Just,” Center for American Progress, February 3, 2021, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/biden-administration-can-now-make-college-affordable-accountable-racially-just/ .

- Marshall Anthony Jr., “Building a College-Educated America Requires Closing Racial Gaps in Attainment,” Center for American Progress, April 6, 2021, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/building-college-educated-america-requires-closing-racial-gaps-attainment/ .

- Aurelia Glass, “The Closing Gender, Education, and Ideological Divides Behind Gen Z’s Union Movement” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2022), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-closing-gender-education-and-ideological-divides-behind-gen-zs-union-movement/ .

- This includes all nonwhite or Hispanic respondents born outside of the United States.

- Kim Parker, “What’s behind the growing gap between men and women in college competition?”, Pew Research Center, November 8, 2021, available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/08/whats-behind-the-growing-gap-between-men-and-women-in-college-completion/ .

- Based on the author’s analysis of 2019 American Community Survey data, using the same methodology as the 2021 sample.

- Diana Boesch and Shilpa Phadke, “When Women Lose All the Jobs: Essential Actions for a Gender-Equitable Recovery” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2021), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/women-lose-jobs-essential-actions-gender-equitable-recovery/ .

- Richard Fry, “Some gender disparities widened in the U.S. workforce during the pandemic,” Pew Research Center, January 14, 2022, available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/01/14/some-gender-disparities-widened-in-the-u-s-workforce-during-the-pandemic/ .

- Beth Almeida and Bela Salas-Betsch, “Fact Sheet: The State of Women in the Labor Market in 2023” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2023), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/fact-sheet-the-state-of-women-in-the-labor-market-in-2023/ .

- The Women’s Initiative, “Gender Matters: Women Disproportionately Report Sexual Harassment in Male-Dominated Industries,” Center for American Progress, August 6, 2018, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/gender-matters/ .

- Mia Ives-Rublee, Rose Khattar, and Anona Neal, “Revolutionizing the Workplace: Why Long COVID and the Increase of Disabled Workers Require a New Approach” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2022), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/revolutionizing-the-workplace-why-long-covid-and-the-increase-of-disabled-workers-require-a-new-approach/ .

- Mia Ives-Rublee, Rose Khattar, and Lily Roberts, “Removing Obstacles for Disabled Workers Would Strengthen the U.S. Labor Market” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2022), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/removing-obstacles-for-disabled-workers-would-strengthen-the-u-s-labor-market/ .

- While some classification schemes combine home health and personal care aides given the similarity of their work, the Census Bureau classifications used in this analysis splits these occupations into distinct categories; had they been combined, they would have constituted the ninth-most-populous occupation for the working class. See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: 31-1120 Home Health and Personal Care Aides,” available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes311120.htm (last accessed March 2023).

- Frank Manzo IV and Erik Thorson, “Union Apprenticeships: The Bachelor’s Degrees of the Construction Industry” (La Grange, IL: Illinois Economic Policy Institute, 2021), available at https://illinoisepi.files.wordpress.com/2021/09/ilepi-union-apprentices-equal-college-degrees-final.pdf .

- Aurelia Glass, David Madland, and Karla Walter, “Prevailing Wages Can Build Good Jobs Into America’s Electric Vehicle Industry” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2022), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/prevailing-wages-can-build-good-jobs-into-americas-electric-vehicle-industry/ .

- Aurelia Glass, David Madland, and Karla Walter, “Raising Wages and Narrowing Pay Gaps With Service Sector Prevailing Wage Laws” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2022), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/raising-wages-and-narrowing-pay-gaps-with-service-sector-prevailing-wage-laws/ .

- David Madland, “Raising Standards for Fast-Food Workers in California: The Powerful Role of a Sectoral Council” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2021), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/raising-standards-fast-food-workers-california/ .

- Mignon Duffy, “Why Improving Low-Wage Health Care Jobs Is Critical for Health Equity,” AMA Journal of Ethics 24 (9) 2022: E871–875, available at https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/why-improving-low-wage-health-care-jobs-critical-health-equity/2022-09 .

- Maggie Corser, “Job Quality and Economic Opportunity in Retail: Key Findings from a National Survey of the Retail Workforce” (Washington: Center for Popular Democracy, 2017), available at https://www.populardemocracy.org/sites/default/files/DataReport-WebVersion-01-03-18.pdf .

- SEIU 775 and the Center for American Progress, “Higher Pay For Caregivers” (Washington: 2021), available at https://seiu775.org/hazardpayreport/ .

- Abigail R. Barker and Linda Li, “The cumulative impact of health insurance on health status,” Health Services Research 55 (2) (2020): 815–822, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7518807/ .

- Sharita Gruberg and Karla Walter, “How historic infrastructure investments can benefit women workers,” The Hill , February 21, 2023, available at https://thehill.com/opinion/white-house/3867722-how-historic-infrastructure-investments-can-benefit-women-workers/ .

- Karla Walter, “Proven State and Local Strategies To Create Good Jobs With IIJA Infrastructure Funds” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2022), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/proven-state-and-local-strategies-to-create-good-jobs-with-iija-infrastructure-funds/ .

- SEIU and the Center for American Progress, “President Biden’s Home Care Proposal Would Create Massive Job Growth in Every State,” August 17, 2021, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/president-bidens-home-care-proposal-create-massive-job-growth-every-state/ .

- Anna Lovejoy, “Top 5 Actions Governors Can Take To Address the Child Care Shortage” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2023), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/top-5-actions-governors-can-take-to-address-the-child-care-shortage/ .

- Karla Walter and Aurelia Glass, “Airport Service Workers Deserve Good Jobs” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2023), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/airport-service-workers-deserve-good-jobs/ .

- David Madland, “Worker Rights Are Getting a Major Shake Up,” Route Fifty, September 8, 2022, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/worker-rights-are-getting-a-major-shake-up/ .

- Richard L. Trumka Protecting the Right to Organize Act of 2023, H.R. 20, 118th Cong., 1st sess. (February 28, 2023), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/20 .