One-word Ofsted ratings for schools to be scrapped immediately

The change follows engagement with the education sector and family of headteacher Ruth Perry, who took her own life after an Osted inspection.

Political reporter @fayebrownSky

Monday 2 September 2024 08:47, UK

One-word Ofsted judgements for state schools are being scrapped with immediate effect in a move that has been hailed as a "landmark moment for children".

Previously, the education watchdog awarded one of four marks to schools it inspects: outstanding, good, requires improvement and inadequate.

From this academic year, four grades will be awarded across the existing sub-categories: quality of education, behaviour and attitudes, personal development and leadership and management, the Department for Education (DfE) has announced.

School report cards will be introduced from September 2025, which will provide parents with a "comprehensive assessment of how schools are performing and ensure that inspections are more effective in driving improvement", it added.

The change follows engagement with the education sector and family of headteacher Ruth Perry , who took her own life after an Ofsted report downgraded her Caversham Primary School in Reading from "outstanding" to "inadequate" over safeguarding concerns.

Last year, a coroner's inquest found the inspection process had contributed to her death.

The DfE said "reductive" single phrase grades "fail to provide a fair and accurate assessment of overall school performance" and the change will help "break down barriers to opportunity".

More on Bridget Phillipson

Free childcare for nine-month-olds available from next week - but rollout comes with 'challenges'

Parents may miss out on first choice free childcare places, education secretary warns

Children to be taught how to spot fake news and 'putrid' conspiracy theories online in wake of riots

Related Topics:

- Bridget Phillipson

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson told Sky News' Breakfast with Kay Burley programme: "We are today making that change because I believe that parents need more information about what goes on within our schools and the system that we've got at the moment just isn't working.

"It's too high stakes, and it doesn't have a sharp enough focus on how we drive up standards in our schools. And that is incredibly important because I want all of our children to get a great education and a great start in life."

The change has been a central mission of the new Labour government, which has vowed to raise standards in state education and generate additional funding through a tax on private school fees .

As part of the announcement today, the government said it will prioritise improvement plans for schools identified as struggling, rather than relying on changing management.

From early 2025, regional improvement teams will be introduced to work with underperforming schools to address areas of weakness.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

In cases of the most serious concern, where schools would have been rated inadequate, the government will continue to intervene.

This could include issuing an academy order, which forces maintained schools to become an academy and which may in some scenarios mean transferring to new management, the DfE said.

Ms Phillipson earlier said: "The need for Ofsted reform to drive high and rising standards for all our children in every school is overwhelmingly clear.

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

Read more from Sky News: Adele to step away from music 'for an incredibly long time' How terror group linked to Taylor Swift gig plot is gaining influence

"The removal of headline grades is a generational reform and a landmark moment for children, parents, and teachers."

She added that single headline grades are "low information for parents and high stakes for schools".

"Parents deserve a much clearer, much broader picture of how schools are performing - that's what our report cards will provide.

"This government will make inspection a more powerful, more transparent tool for driving school improvement. We promised change, and now we are delivering."

Reforms 'could go further'

The announcement comes as pupils return to the classroom this week.

The removal of single headline grades will apply to state schools due to be inspected this academic year, with other settings like independent schools and colleges expected to follow.

Keep up with all the latest news from the UK and around the world by following Sky News

The plans have been welcomed by teaching unions, who have long called for reform.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the National Association of Headteachers, said: "We have been clear that simplistic one-word judgments are harmful and we are pleased the government has taken swift action to remove them."

👉 Tap here to follow the Sky News Daily podcast - 20 minutes on the biggest stories every day 👈

However, NASUWT general secretary Dr Patrick Roach said while the new government has "made the right decision", it could go further and "end the fallacy that academy conversion is the only route to securing the improvements our schools need".

"Whilst today's announcements are an important step in the right direction, it remains the case that in the absence of root and branch reform to fix the foundations of the broken accountability system, teachers and school leaders will continue to work in a system that remains flawed," he said.

Watch Sky News' The Politics Hub this evening at 7pm.

Related Topics

APA Style for beginners

Then check out some frequently asked questions:

What is APA Style?

Why use apa style in high school, how do i get started with apa style, what apa style products are available, your help wanted.

APA Style is the most common writing style used in college and career. Its purpose is to promote excellence in communication by helping writers create clear, precise, and inclusive sentences with a straightforward scholarly tone. It addresses areas of writing such as how to

- format a paper so it looks professional;

- credit other people’s words and ideas via citations and references to avoid plagiarism; and

- describe other people with dignity and respect using inclusive, bias-free language.

APA Style is primarily used in the behavioral sciences, which are subjects related to people, such as psychology, education, and nursing. It is also used by students in business, engineering, communications, and other classes. Students use it to write academic essays and research papers in high school and college, and professionals use it to conduct, report, and publish scientific research .

High school students need to learn how to write concisely, precisely, and inclusively so that they are best prepared for college and career. Here are some of the reasons educators have chosen APA Style:

- APA Style is the style of choice for the AP Capstone program, the fastest growing AP course, which requires students to conduct and report independent research.

- APA Style helps students craft written responses on standardized tests such as the SAT and ACT because it teaches students to use a direct and professional tone while avoiding redundancy and flowery language.

- Most college students choose majors that require APA Style or allow APA Style as an option. It can be overwhelming to learn APA Style all at once during the first years of college; starting APA Style instruction in high school sets students up for success.

High school students may also be interested in the TOPSS Competition for High School Psychology Students , an annual competition from the APA Teachers of Psychology in Secondary Schools for high school students to create a short video demonstrating how a psychological topic has the potential to benefit their school and/or local community and improve people’s lives.

Most people are first introduced to APA Style by reading works written in APA Style. The following guides will help with that:

|

|

|

|

| Handout explaining how journal articles are structured and how to become more efficient at reading and understanding them |

|

| Handout exploring the definition and purpose of abstracts and the benefits of reading them, including analysis of a sample abstract |

Many people also write research papers or academic essays in APA Style. The following resources will help with that:

|

|

|

|

| Guidelines for setting up your paper, including the title page, font, and sample papers |

|

| More than 100 reference examples of various types, including articles, books, reports, films, social media, and webpages |

|

| Handout comparing example APA Style and MLA style citations and references for four common reference types (journal articles, books, edited book chapters, and webpages and websites) |

|

| Handout explaining how to understand and avoid plagiarism |

|

| Checklist to help students write simple student papers (typically containing a title page, text, and references) in APA Style |

|

| Handout summarizing APA’s guidance on using inclusive language to describe people with dignity and respect, with resources for further study |

|

| Free tutorial providing an overview of all areas of APA Style, including paper format, grammar and usage, bias-free language, punctuation, lists, italics, capitalization, spelling, abbreviations, number use, tables and figures, and references |

|

| Handout covering three starter areas of APA Style: paper format, references and citations, and inclusive language |

Instructors will also benefit from using the following APA Style resources:

|

|

|

|

| Recording of a webinar conducted in October 2023 to refresh educators’ understanding of the basics of APA Style, help them avoid outdated APA Style guidelines (“zombie guidelines”), debunk APA Style myths (“ghost guidelines”), and help students learn APA Style with authoritative resources |

|

| Recording of a webinar conducted in May 2023 to help educators understand how to prepare high school students to use APA Style, including the relevance of APA Style to high school and how students’ existing knowledge MLA style can help ease the transition to APA Style (register for the webinar to receive a link to the recording) |

|

| Recording of a webinar conducted in September 2023 to help English teachers supplement their own APA Style knowledge, including practical getting-started tips to increase instructor confidence, the benefits of introducing APA Style in high school and college composition classes, some differences between MLA and APA Style, and resources to prepare students for their future in academic writing |

|

| Poster showing the three main principles of APA Style: clarity, precision, and inclusion |

|

| A 30-question activity to help students practice using the APA Style manual and/or APA Style website to look up answers to common questions |

In addition to all the free resources on this website, APA publishes several products that provide comprehensive information about APA Style:

|

|

|

|

| The official APA Style resource for students, covering everything students need to know to write in APA Style |

|

| The official source for APA Style, containing everything in the plus information relevant to conducting, reporting, and publishing psychological research |

|

| APA Style’s all-digital workbook with interactive questions and graded quizzes to help you learn and apply the basic principles of APA Style and scholarly writing; integrates with popular learning management systems, allowing educators to track and understand student progress |

|

| APA’s online learning platform with interactive lessons about APA Style and academic writing, reference management, and tools to create and format APA Style papers |

The APA Style team is interested in developing additional resources appropriate for a beginner audience. If you have resources you would like to share, or feedback on this topic, please contact the APA Style team .

Free newsletter

Apa style monthly.

Subscribe to the APA Style Monthly newsletter to get tips, updates, and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

- Services & Software

How I Use AI to Catch Cheaters at School

It's getting harder to spot by the day, but here are some ways you can use ChatGPT to spot student papers using ChatGPT.

It's a tale as old as teaching -- a student, for one reason or another, uses someone else's work to complete their assignment. Only in 2024, that someone else could be an artificial intelligence tool.

The allure is understandable. Away with those shady essay writing services where a student has to plonk down real cash for an unscrupulous person to write them 1,200 words on the fall of the Roman Empire. An AI writing tool can do that for free in 30 seconds flat.

As a professor of strategic communications, I encounter students using AI tools like ChatGPT , Grammarly and EssayGenius on a regular basis. It's usually easy to tell when a student has used one of these tools to draft their entire work. The tell-tale signs include ambiguous language and a super annoying tendency for AI to spit out text with the assignment prompt featured broadly.

For example, a student might use ChatGPT -- an AI tool that uses large language model learning and a conversational question and answer format to provide query results -- to write a short essay response to a prompt by simply copying and pasting the essay question into the tool.

Take this prompt: In 300 words or less, explain how this SWAT and brand audit will inform your final pitch.

This is ChatGPT's result:

I have received responses like this, or those very close to it, a few times in my tenure as a teacher, and one of the most recognizable red flags is the amount of instances in which key terms from the prompt are used in the final product.

Students don't normally repeat key terms from the prompt in their work in this way, and the results read closer to old-school SEO-driven copy meant to define these terms rather than a unique essay meant to demonstrate an understanding of subject matter.

But can teachers use AI tools to catch students using AI tools? I came up with some ways to be smarter in spotting artificial intelligence in papers.

Catching cheaters with AI

Here's how to use AI tools to catch cheaters in your class:

- Understand AI capabilities : There are AI tools on the market now that can scan an assignment and its grading criteria to provide a fully written, cited and complete piece of work in a matter of moments. Familiarizing yourself with these tools is the first step in the war against AI-driven integrity violations.

- Do as the cheaters do: Before the semester begins, copy and paste all your assignments into a tool like ChatGPT and ask it to do the work for you. When you have an example of the type of results it provides specifically in response to your assignments, you'll be better equipped to catch robot-written answers. You could also use a tool designed specifically to spot AI writing in papers .

- Get a real sample of writing: At the beginning of the semester, require your students to submit a simple, fun and personal piece of writing to you. The prompt should be something like "200 words on what your favorite toy was as a child," or "Tell me a story about the most fun you ever had." Once you have a sample of the student's real writing style in hand, you can use it later to have an AI tool review that sample against what you suspect might be AI-written work.

- Ask for a rewrite : If you suspect a student of using AI to cheat on their assignment, take the submitted work and ask an AI tool to rewrite the work for you. In most cases I've encountered, an AI tool will rewrite its own work in the laziest manner possible, substituting synonyms instead of changing any material elements of the "original" work.

Here's an example:

Now, let's take something an actual human (me) wrote, my CNET bio:

The phrasing is changed, extracting much of the soul in the writing and replacing it with sentences that are arguably more clear and straightforward. There are also more additions to the writing, presumably for further clarity.

The most important part about catching cheaters who use AI to do their work is having a reasonable amount of evidence to show the student and the administration at your school if it comes to that. Maintaining a skeptical mind when grading is vital, and your ability to demonstrate ease of use and understanding with these tools will make your case that much stronger.

Good luck out there in the new AI frontier, fellow teachers, and try not to be offended when a student turns in work written by their robot collaborator. It's up to us to make the prospect of learning more alluring than the temptation to cheat.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Recess Duty

How we tried—and failed—to get our kids more outside time during the school day..

As the new academic year approaches, I check off the back-to-school tasks— label folders , disinfect lunch box , buy overpriced required school shoes that will result in blisters and whines —and I also check to see which states, if any, have adopted new laws to require recess. I’m happy to report that California and Washington are joining nine other states that require daily recess this year. This is a change I tried to make in my town years ago—and failed.

Our group, Alabama Families for Recess , began one evening in September 2017 on a front porch during a party. At this time, I had a kindergartner in public school and was shocked by the lack of recess. The result was a pent-up child so tired from being on-task all day that the night ended with a tantrum or, worse, quiet crying in the tub. She simply hadn’t had enough of a break in her seven-hour day, and my efforts to take her to a playground first thing after pickup couldn’t counteract that.

The other parents shared similar stories: exhaustion, irritability, kids getting in trouble at school for rambunctious behavior, and worst of all—curiosity being replaced by apathy. So, wine in hand, we resolved to talk to the principal. It seemed like such a practical, free, improvement. “Who would oppose recess?” I thought. But in advocating for free time during a child’s school day, we had no idea the cultural quagmire we were stepping into.

The principal explained that since our children attended an academically focused magnet school using the International Baccalaureate curriculum , there simply was not room in the schedule to have a daily recess and still comply with the state’s requirements. What’s more, this elementary school serves a student population that is 79 percent students of color and 43 percent economically disadvantaged; it’s ranked fourth in the state for magnet schools. Students won a lottery to attend, so the school’s achievements weren’t connected to admitting only those already performing at advanced levels. The school was getting amazing results by any measurable standards, so I can understand her hesitation to change.

While I could see the principal’s perspective, the research simply didn’t support it. Recess is heavily linked with increased productivity, higher retention rates , and better mental health, and is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics , and many other child advocacy groups. And while the requirements for the IB program are demanding, the principal could have simply stopped allowing teachers to take away the few recess breaks they did have scheduled. What’s more, while I agreed an IB program would benefit my child academically, I couldn’t ignore her stress levels. Chronic stress can lead to an overactive amygdala , which can then lead to mental health problems later in life.

The principal also pointed to daily PE as an adequate supplement, but those who study child development say otherwise. Children need the unstructured time of recess in order to self-regulate, imagine new games, problem-solve, mitigate conflict, develop internal agency, and refine social skills. Simply put, kids need experience at being in charge of their own time. Lack of that experience, I think, creates the tendency for older kids to fill blank space by staring into the abyss of their phones.

We realized we would need to appeal to a higher authority—and this is where local advocacy can feel like riding a roller coaster after eating a tray of loaded nachos. We had a core group of approximately eight parents willing to take on the fight, including my husband. The rest, like me, had more of an ancillary role.

Thankfully, we had the key component to community action: a leader willing to delve into the inscrutable bureaucratic muck that feels designed to stall groups like mine. Acting off the principal’s information that prohibition of recess came from the state, our leader, Stephanie Jackson, contacted the Alabama Department of Education, the National PTA, and our State Board of Education representative. All of them pointed out that recess was recommended under the Alabama Course of Study and advised her to work with her local school system.

The local superintendent, however, refused to meet with the group. The initiative felt as if it had reached a dead end. But then Jackson talked to someone at the National PTA who set up a phone call with parents who had secured Florida’s recess law of 20 minutes a day.

They provided a model for success. We started an online petition calling for a 20-minute daily recess for K–fifth graders that could not be taken away as punishment. We circulated it online and at community events. We created a Facebook page and invited those who agreed to “like” our page. We did our research and made handouts chock-full with facts on how recess contributes to learning and promotes mental health—along with cutesy graphics to make the flyers more attractive.

With 1,400 signatures and the retirement of the former superintendent, we felt the climate had shifted in our favor, so Jackson asked again for a meeting—and got it.

The new superintendent smiled, shook hands, and agreed to the benefits of daily recess. My husband and the two others who were at that meeting returned with what they thought was good news. My daughter literally jumped on her bed for joy. “I’ll be able to talk to my friends now,” she said.

But come August, my daughter came home and frowned: “No recess.” Sure enough, recess had only been recommended , not required. That school year, she had recess maybe once a month.

Now, a couple qualifications here. First, the decisions made by the superintendent’s office in the end were behind closed doors. (When I reached out in the course of writing this essay, to find out more about this process, they acknowledged receipt of the email but did not comment.) So, I can only speculate on what happened based on the limited knowledge I have. Second, I don’t want to make this another story about how backward Alabama is. I have a genuine love for Mobile and witness on a daily basis many people who have dedicated their lives to change the structural systems that lead to endemic poverty, crime, and discrimination of all kinds.

What happened in Mobile is emblematic of a national problem more than a regional one. As one of the parents in the group, Lisa Roddy, commented to me, “The diminishment of recess at school runs parallel to the diminishment of unsupervised play at home.” Indeed, my own childhood spent working in the garden to sell produce at the local farmers market and roaming the neighborhood with friends is something of the past, replaced by structured activities like team sports, day camps, online gaming—and mountains of homework.

The reasons behind the reduction of unstructured time stem from some profound social, cultural, and political shifts that occurred in the ’80s. A benchmark event often cited is the 1983 landmark education commission report that found American children to be lagging behind other developed nations—a finding that led to more standardized testing, increased homework loads, and tougher college admissions standards.

Another change was a restructuring of the tax system and reduction of federal student aid under the Reagan administration, which has placed a higher burden on families to pay for college. And one route to pay for the skyrocketing costs (Boston University now costs $90,000 a year, as Slate recently reported ) is for students to earn academic or athletic scholarships.

Increased media attention over some high-profile abductions such as Adam Walsh (which led to the creation of the TV show America’s Most Wanted and children’s faces appearing on milk cartons ) terrified caregivers in the ’80s. Also, the CDC began combining child abductions by strangers and noncustodial parents to calculate kidnapping rates, so that the potential risk appeared to skyrocket overnight. These fears created a cultural imperative to supervise children’s play every minute.

Some teachers told me in confidence that the ability to offer recess as a reward, to compel good student behavior, was simply too powerful of a tool to give up. I also suspect there are liability issues; principals didn’t want yet another reason for parents to call and complain about what someone said to someone on the playground. Because let’s be honest: Playgrounds can be fertile ground for bullying. (I know this well: When I was a second grader, I created a school paper where the front-page news consisted of who-kissed-who by the swing set and who-knocked-who off the slide.)

After my experience with recess advocacy, I’m seeing the solution being akin to what some are advocating to counter teens’ use of social media. We need governmental regulations to help the parents who are plugging holes in the dam. The problem of no recess is too entrenched in our culture at this point. Stephanie Jackson was well on her way to introduce a bill to the Alabama Legislature—and even had a potential sponsor. Then COVID hit, and progress stalled out.

While we didn’t achieve our immediate goals, positive change did occur. The 2019 Alabama Course of Study adopted our group’s language regarding recess. It states that “recess is a necessary break from the rigors of concentrated academic challenges” and that it is “inappropriate” for teachers to withhold recess as a “behavioral management tool.” These, however, were recommendations, rather than requirements. Since then, the Alabama PTA partnered with us and has taken up the charge. On the group’s page , one can find actionable items to promote recess in one’s own school district—and how to pass a recess-requirement bill. (Pictures of our group are posted there, too.) With today’s teen mental health crisis, it is more important than ever to examine unhealthy habits contributing to stress and anxiety, including those that may have started in elementary school.

This year, my daughter is in seventh grade. In fourth grade, we had to move schools to better serve her dyslexia. A bonus: The new school had recess. I asked her recently what it was like suddenly having recess, and she rolled her eyes, as kids her age will, and said: “That never made sense. I could focus so much better after I went outside.”

As we move into the college arms race, I have to remind myself I grew up with an abundance of chores and free time—and that has served me, not hindered me. As life becomes busier with the new school year, I am determined to ensure daily unstructured time for my daughter—time other than the minutes she spends with her nose pressed to the car window on our way to the next event. After all, we are raising children, not careers.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Single headline Ofsted grades scrapped in landmark school reform

Government pushes ahead with reform agenda by scrapping single headline Ofsted judgements for schools with immediate effect

Single headline grades for schools will be scrapped with immediate effect to boost school standards and increase transparency for parents, the government has announced today.

Reductive single headline grades fail to provide a fair and accurate assessment of overall school performance across a range of areas and are supported by a minority of parents and teachers.

The change delivers on the government’s mission to break down barriers to opportunity and demonstrates the Prime Minister’s commitment to improve the life chances of young people across the country.

For inspections this academic year, parents will see four grades across the existing sub-categories: quality of education, behaviour and attitudes, personal development and leadership & management.

This reform paves the way for the introduction of School Report Cards from September 2025, which will provide parents with a full and comprehensive assessment of how schools are performing and ensure that inspections are more effective in driving improvement. Recent data shows that reports cards are supported by 77% of parents.

The government will continue to intervene in poorly performing schools to ensure high school standards for children.

Bridget Phillipson, Education Secretary, said:

The need for Ofsted reform to drive high and rising standards for all our children in every school is overwhelmingly clear. The removal of headline grades is a generational reform and a landmark moment for children, parents, and teachers. Single headline grades are low information for parents and high stakes for schools. Parents deserve a much clearer, much broader picture of how schools are performing – that’s what our report cards will provide. This government will make inspection a more powerful, more transparent tool for driving school improvement. We promised change, and now we are delivering.

As part of today’s announcement, where schools are identified as struggling, government will prioritise rapidly getting plans in place to improve the education and experience of children, rather than relying purely on changing schools’ management.

From early 2025, the government will also introduce Regional Improvement Teams that will work with struggling schools to quickly and directly address areas of weakness, meeting a manifesto commitment.

The Education Secretary has already begun to reset relations with education workforces, supporting the Government’s pledge to recruit 6,500 new teachers, and reform to Ofsted marks another key milestone.

Today’s announcement follows engagement with the sector and family of headteacher Ruth Perry, after a coroner’s inquest found the Ofsted inspection process had contributed to her death.

The government will work closely with Ofsted and relevant sectors and stakeholders to ensure that the removal of headline grades is implemented smoothly.

Jason Elsom, Chief Executive of Parentkind, said:

We welcome the decision by the Secretary of State to prioritise Ofsted reform. The move to end single-word judgements as soon as practical, whilst giving due care and attention to constructing a new and sustainable accountability framework during the year ahead, is the right balance for both schools and parents. Most parents understand the need for school inspection, but they want that inspection to help schools to improve as well as giving a verdict on the quality of education their children are receiving. When we spoke to parents about what was important to them, their children being happy at school was a big talking point and should not be overlooked. Parents have been very clear that they want to see changes to the way Ofsted reports back after visiting a school, and it is welcome to see a clear timetable being set out today for moving towards a report card that will give parents greater clarity of the performance of their children’s school. We need to make sure that we get this right for parents, as well as schools. There is much more we can do to include the voice of parents in Ofsted inspections and reform of our school system, and today’s announcement is a big step in the right direction.

Paul Whiteman, General Secretary of National Association of Headteachers, said:

The scrapping of overarching grades is a welcome interim measure. We have been clear that simplistic one-word judgements are harmful, and we are pleased the government has taken swift action to remove them. School leaders recognise the need for accountability but it must be proportionate and fair and so we are pleased to see a stronger focus on support for schools instead of heavy-handed intervention. There is much work to do now in order to design a fundamentally different long-term approach to inspection and we look forward to working with government to achieve that.

Where necessary, in cases of the most serious concern, government will continue to intervene, including by issuing an academy order, which may in some cases mean transferring to new management. Ofsted will continue to identify these schools – which would have been graded as inadequate.

The government also currently intervenes where a school receives two or more consecutive judgements of ‘requires improvement’ under the ‘2RI’ policy. With the exception of schools already due to convert to academies this term, this policy will change. The government will now put in place support for these schools from a high performing school, helping to drive up standards quickly.

Today’s changes build on the recently announced Children’s Wellbeing Bill, which will put children at the centre of education and make changes to ensure every child is supported to achieve and thrive.

Share this page

The following links open in a new tab

- Share on Facebook (opens in new tab)

- Share on Twitter (opens in new tab)

Updates to this page

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

Get the best experience and stay connected to your community with our Spectrum News app. Learn More

Continue in Browser

Get hyperlocal forecasts, radar and weather alerts.

Please enter a valid zipcode.

Where have all the children gone? Rise of homeschooling takes a transformative look on education

ROCHESTER, N.Y. — According to the Empire Center for Public Policy , families in New York state have flocked to home education at rates twice the national average. According to Skill Ademia in 2019, prior to remote learning, approximately 2.5 million students were homeschooled in the United States. This number has risen significantly, with estimates indicating that almost 4 million students are being homeschooled nationwide.

To meet the needs of the community, Greece Public Library has been distributing updated homeschool kids providing supplemental materials for students' required curriculum.

Being a parent can often be a handful, but for Léa Bouillon, she has chosen to wear many different hats; from being a mother of three, teaching French and English and even exploring classical music.

They are lessons, Bouillon says, you would not typically find in your everyday classroom.

“I'm an opera singer and I have a degree in French literature, so we focus on classical arts, classical music artists,” Bouillon said. “I try to maintain a balance between stretching them to something that is new and pointing them in a new direction, that they can really relate to.”

Which is why Bouillon has brought the classroom to her own home.

“What is wonderful about homeschooling is that you really get to think about your own education all over again and maybe reconsider your own strengths and weaknesses and how they can be improved,” Bouillon said.

According to the Empire Center for Public Policy, families in New York state have flocked to home education at rates twice the national average. Bouillon and thousands of other families making the switch have made New York second in the nation for homeschooling growth.

“Really choose a curriculum, to choose an education that is a little more specific to your children,” Bouillon said. “I wasn't homeschooled, so I don't know what I'm doing. So I think it used to be that there weren't a lot of resources for some parts of homeschooling. And now thankfully there are so many resources.”

As public schools have seen the surge, so have their local libraries. Distributing homeschool kits , Greece Public Library provides materials that cover a variety of topics.

Librarian April Newman has spent over a year crafting materials for families like the Bouillons in hopes they are provided the proper supplemental materials.

“The supplemental materials include music and art and STEM, Vocabulary, Spanish,” librarian April Newman said. “So it'll be things that people don't have in their home school curriculum, per se, but they want to have an add on because the curriculum for the home schools and the co-ops, they're not going to be including all subject matters sometime. So it's really helpful for the parents if we give them some new materials.”

As families continue to show a growing interest in alternative learning models, Bouillon has found beauty in being her own teacher.

“Just to be the one who gets to pour into your children and build this deep relationship with them is a real privilege,” Bouillon said.

And she's finding the world to be the true classroom.

Newsletter: Giving high school students options besides college

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Good morning. It is Wednesday, Aug. 28, and we’re in the last week before the unofficial end of summer. Here’s what’s happening in Opinion.

Editorial Writer Karin Klein has covered education for years and watching the Democratic National Convention last week, she picked up on a new theme from party leaders. They were talking a lot more about the need to create well-paid careers for people who don’t obtain a bachelor’s degree. She wrote about this in the recent editorial The idea that success does not require a college degree gets space on DNC stage, and I asked her to share more insight with newsletter readers. Below are her answers.

What’s changed in the rhetoric on college?

For a long time, Democratic leadership was pushing the “college for everyone” movement. In 2009, former President Obama vowed that “by 2020, this nation will once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.” The idea at the time, part of a push by former Microsoft CEO Bill Gates, was that the country would lose some kind of global jobs war with other countries. Gates said we would be short 11 million skilled workers if vast numbers of students weren’t added to the college rolls.

Consider, close to 40% of Cal State students don’t get a bachelor’s degree within six years More than 40% of four-year college grads are underemployed — working in jobs that really don’t need a degree. Americans were seeing this and rightly questioning whether so many people needed a degree, especially given the unsolved student debt question. They were ignored for too long and now they are being heard. It was remarkable to hear Obama say during the DNC, “College shouldn’t be the only ticket to the middle class.”

You recently wrote a book about this called “Rethinking College: A Guide to Thriving Without a Degree.” Why did you decide to write about this?

No one is helping students who don’t want or aren’t ready to go to college figure out their next step. I wanted to help young people (or older people) who are thinking, “I don’t really want to go for a bachelor’s degree, but I don’t know what I can do without one or what kinds of work are available and how I would go about getting them.” I’m filling what I call the “guidance gap” at high schools.

My goal is to inspire this group of students to know that they don’t have to take the conventional high-school-straight-to-college route and that following the path that’s right for them as individuals is as admirable as going to college. And to give them helpful, specific information about the many career possibilities open to them.

School counselors are pressured to get students into college — not to mention that most of them have too heavy a load to tailor their advice to individual needs. Beyond college, they mostly have two things to suggest: the skilled trades such as welding, or joining the military. Both of those are valid options and are in my book, but counselors aren’t aware of how much more there is or how students can link up to the job world. Just to name a few, there are the creative fields, entrepreneurialism, travel and outdoor work, white-collar apprenticeships, plus companies and governments that have dropped degree requirements for many professional jobs.

Why is this an important conversation now, and what else should we be talking about in terms of jobs and college?

Obviously, student debt is a big one. Our current model of on-campus, finish-in-four-years college isn’t working well for too many people. This doesn’t call for tweaking but for some wholesale changes. Most people are surprised to learn that nearly 30% of community college grads out-earn the average holder of a bachelor’s degree, and that 59% of people who went to college because they were pressured into it or didn’t know what else to do end up saying college was a waste.

In truth, our way of education is too narrowly focused, too irrelevant to student lives and their diverse talents. And, strangely, it is too performative and not focused enough on the love of learning that should be a lifelong pursuit and pleasure whether someone goes to college or not.

The ideas in Project 2025? Reagan tried them, and the nation suffered . The Heritage Foundation’s 1981 publication “The Mandate for Leadership” helped shape President Reagan’s policy framework, writes Joel Edward Goza, a professor of ethics at Simmons College of Kentucky. “If today’s economic inequality, racial unrest and environmental degradation represent some of our greatest political challenges, we would do well to remember that Reagan and the Heritage Foundation were the preeminent engineers of these catastrophes.”

Ignore my brother Bobby, Max Kennedy says . “Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine I would be motivated to write something of this nature,” Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s brother writes after the independent candidate ended his presidential campaign and endorsed Donald Trump. “Trump was exactly the kind of arrogant, entitled bully my father used to prosecute.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Parole consideration for those sentenced to life behind bars 35 years ago? It’s the right thing to do. Senate Bill 94 is a reasonable proposal to allow sentence review for several hundred aging California prisoners who were sent to prison for life without parole before 1990. “Pragmatism and a measured sense of justice, rather than sympathy, are the rationales for this bill,” The Times’ editorial board writes. “There is diminishing value in continuing to imprison people for violent crimes they committed long ago when they were young and stupid.”

Trump keeps flip-flopping on abortion. American women are so over it. Columnist LZ Granderson looks at how Donald Trump’s position on abortion changes for political expediency. “In 2022, he crowed about what his Supreme Court had done. Now it’s 2024, and he’s struggling to meet younger women at the polls, so he’s back to making empty promises.”

More from opinion

From our columnists

- Robin Abcarian: 17-year-old Gus Walz uttered the Democratic National Convention’s three most memorable words

- Jonah Goldberg: Kamala Harris and Donald Trump both call for unity . Here’s why they’re wrong

From guest contributors

- Are American Jews losing their long-standing political home in the Democratic Party?

- L.A. could train the next Simone Biles . But only if we invest in creating opportunities

- Don’t believe Trump’s politicking about Biden’s Afghanistan withdrawal

From the Editorial Board

- November election could make — or break — reproductive freedom

- Why the rush? Hasty L.A. school bond vote leaves many questions unanswered

Letters to the Editor

- I was deployed to Iraq. Tim Walz’s military service deserves gratitude

- Matthew Perry deserves justice, but what about addicts who die without being famous?

- CEQA hasn’t been overhauled. That’s good news for Californians

- L.A. needs to tell property owners to fix our broken sidewalks

Stay in touch.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to our other newsletters and to The Times . As always, you can share your feedback by emailing me at [email protected] .

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Kerry Cavanaugh is an assistant editor and editorial writer covering Los Angeles and Southern California, with a focus on housing, transportation and environmental issues. Prior to joining the board, she was a producer on KCRW’s “To the Point” and “Which Way, L.A.” Before that, she spent a decade at the L.A. Daily News, where she covered L.A. and California politics and wrote a column on local government issues. She’s a graduate of New York University and Columbia Journalism School.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Editorial: The federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour is poverty pay. It’s time to raise it

Op-comic: Summer may be ending, but we still need ways to beat the heat

Opinion: Actors and writers celebrated last year’s labor victory. Now the cheering seems premature

Letters to the Editor: I was a rare female student at Caltech in the 1960s. It’s come a long way

Samantha Putterman, PolitiFact Samantha Putterman, PolitiFact

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/fact-checking-warnings-from-democrats-about-project-2025-and-donald-trump

Fact-checking warnings from Democrats about Project 2025 and Donald Trump

This fact check originally appeared on PolitiFact .

Project 2025 has a starring role in this week’s Democratic National Convention.

And it was front and center on Night 1.

WATCH: Hauling large copy of Project 2025, Michigan state Sen. McMorrow speaks at 2024 DNC

“This is Project 2025,” Michigan state Sen. Mallory McMorrow, D-Royal Oak, said as she laid a hardbound copy of the 900-page document on the lectern. “Over the next four nights, you are going to hear a lot about what is in this 900-page document. Why? Because this is the Republican blueprint for a second Trump term.”

Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic presidential nominee, has warned Americans about “Trump’s Project 2025” agenda — even though former President Donald Trump doesn’t claim the conservative presidential transition document.

“Donald Trump wants to take our country backward,” Harris said July 23 in Milwaukee. “He and his extreme Project 2025 agenda will weaken the middle class. Like, we know we got to take this seriously, and can you believe they put that thing in writing?”

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, Harris’ running mate, has joined in on the talking point.

“Don’t believe (Trump) when he’s playing dumb about this Project 2025. He knows exactly what it’ll do,” Walz said Aug. 9 in Glendale, Arizona.

Trump’s campaign has worked to build distance from the project, which the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, led with contributions from dozens of conservative groups.

Much of the plan calls for extensive executive-branch overhauls and draws on both long-standing conservative principles, such as tax cuts, and more recent culture war issues. It lays out recommendations for disbanding the Commerce and Education departments, eliminating certain climate protections and consolidating more power to the president.

Project 2025 offers a sweeping vision for a Republican-led executive branch, and some of its policies mirror Trump’s 2024 agenda, But Harris and her presidential campaign have at times gone too far in describing what the project calls for and how closely the plans overlap with Trump’s campaign.

PolitiFact researched Harris’ warnings about how the plan would affect reproductive rights, federal entitlement programs and education, just as we did for President Joe Biden’s Project 2025 rhetoric. Here’s what the project does and doesn’t call for, and how it squares with Trump’s positions.

Are Trump and Project 2025 connected?

To distance himself from Project 2025 amid the Democratic attacks, Trump wrote on Truth Social that he “knows nothing” about it and has “no idea” who is in charge of it. (CNN identified at least 140 former advisers from the Trump administration who have been involved.)

The Heritage Foundation sought contributions from more than 100 conservative organizations for its policy vision for the next Republican presidency, which was published in 2023.

Project 2025 is now winding down some of its policy operations, and director Paul Dans, a former Trump administration official, is stepping down, The Washington Post reported July 30. Trump campaign managers Susie Wiles and Chris LaCivita denounced the document.

WATCH: A look at the Project 2025 plan to reshape government and Trump’s links to its authors

However, Project 2025 contributors include a number of high-ranking officials from Trump’s first administration, including former White House adviser Peter Navarro and former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson.

A recently released recording of Russell Vought, a Project 2025 author and the former director of Trump’s Office of Management and Budget, showed Vought saying Trump’s “very supportive of what we do.” He said Trump was only distancing himself because Democrats were making a bogeyman out of the document.

Project 2025 wouldn’t ban abortion outright, but would curtail access

The Harris campaign shared a graphic on X that claimed “Trump’s Project 2025 plan for workers” would “go after birth control and ban abortion nationwide.”

The plan doesn’t call to ban abortion nationwide, though its recommendations could curtail some contraceptives and limit abortion access.

What’s known about Trump’s abortion agenda neither lines up with Harris’ description nor Project 2025’s wish list.

Project 2025 says the Department of Health and Human Services Department should “return to being known as the Department of Life by explicitly rejecting the notion that abortion is health care.”

It recommends that the Food and Drug Administration reverse its 2000 approval of mifepristone, the first pill taken in a two-drug regimen for a medication abortion. Medication is the most common form of abortion in the U.S. — accounting for around 63 percent in 2023.

If mifepristone were to remain approved, Project 2025 recommends new rules, such as cutting its use from 10 weeks into pregnancy to seven. It would have to be provided to patients in person — part of the group’s efforts to limit access to the drug by mail. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a legal challenge to mifepristone’s FDA approval over procedural grounds.

WATCH: Trump’s plans for health care and reproductive rights if he returns to White House The manual also calls for the Justice Department to enforce the 1873 Comstock Act on mifepristone, which bans the mailing of “obscene” materials. Abortion access supporters fear that a strict interpretation of the law could go further to ban mailing the materials used in procedural abortions, such as surgical instruments and equipment.

The plan proposes withholding federal money from states that don’t report to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention how many abortions take place within their borders. The plan also would prohibit abortion providers, such as Planned Parenthood, from receiving Medicaid funds. It also calls for the Department of Health and Human Services to ensure that the training of medical professionals, including doctors and nurses, omits abortion training.

The document says some forms of emergency contraception — particularly Ella, a pill that can be taken within five days of unprotected sex to prevent pregnancy — should be excluded from no-cost coverage. The Affordable Care Act requires most private health insurers to cover recommended preventive services, which involves a range of birth control methods, including emergency contraception.

Trump has recently said states should decide abortion regulations and that he wouldn’t block access to contraceptives. Trump said during his June 27 debate with Biden that he wouldn’t ban mifepristone after the Supreme Court “approved” it. But the court rejected the lawsuit based on standing, not the case’s merits. He has not weighed in on the Comstock Act or said whether he supports it being used to block abortion medication, or other kinds of abortions.

Project 2025 doesn’t call for cutting Social Security, but proposes some changes to Medicare

“When you read (Project 2025),” Harris told a crowd July 23 in Wisconsin, “you will see, Donald Trump intends to cut Social Security and Medicare.”

The Project 2025 document does not call for Social Security cuts. None of its 10 references to Social Security addresses plans for cutting the program.

Harris also misleads about Trump’s Social Security views.

In his earlier campaigns and before he was a politician, Trump said about a half-dozen times that he’s open to major overhauls of Social Security, including cuts and privatization. More recently, in a March 2024 CNBC interview, Trump said of entitlement programs such as Social Security, “There’s a lot you can do in terms of entitlements, in terms of cutting.” However, he quickly walked that statement back, and his CNBC comment stands at odds with essentially everything else Trump has said during the 2024 presidential campaign.

Trump’s campaign website says that not “a single penny” should be cut from Social Security. We rated Harris’ claim that Trump intends to cut Social Security Mostly False.

Project 2025 does propose changes to Medicare, including making Medicare Advantage, the private insurance offering in Medicare, the “default” enrollment option. Unlike Original Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans have provider networks and can also require prior authorization, meaning that the plan can approve or deny certain services. Original Medicare plans don’t have prior authorization requirements.

The manual also calls for repealing health policies enacted under Biden, such as the Inflation Reduction Act. The law enabled Medicare to negotiate with drugmakers for the first time in history, and recently resulted in an agreement with drug companies to lower the prices of 10 expensive prescriptions for Medicare enrollees.

Trump, however, has said repeatedly during the 2024 presidential campaign that he will not cut Medicare.

Project 2025 would eliminate the Education Department, which Trump supports

The Harris campaign said Project 2025 would “eliminate the U.S. Department of Education” — and that’s accurate. Project 2025 says federal education policy “should be limited and, ultimately, the federal Department of Education should be eliminated.” The plan scales back the federal government’s role in education policy and devolves the functions that remain to other agencies.

Aside from eliminating the department, the project also proposes scrapping the Biden administration’s Title IX revision, which prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. It also would let states opt out of federal education programs and calls for passing a federal parents’ bill of rights similar to ones passed in some Republican-led state legislatures.

Republicans, including Trump, have pledged to close the department, which gained its status in 1979 within Democratic President Jimmy Carter’s presidential Cabinet.

In one of his Agenda 47 policy videos, Trump promised to close the department and “to send all education work and needs back to the states.” Eliminating the department would have to go through Congress.

What Project 2025, Trump would do on overtime pay

In the graphic, the Harris campaign says Project 2025 allows “employers to stop paying workers for overtime work.”

The plan doesn’t call for banning overtime wages. It recommends changes to some Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, regulations and to overtime rules. Some changes, if enacted, could result in some people losing overtime protections, experts told us.

The document proposes that the Labor Department maintain an overtime threshold “that does not punish businesses in lower-cost regions (e.g., the southeast United States).” This threshold is the amount of money executive, administrative or professional employees need to make for an employer to exempt them from overtime pay under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

In 2019, the Trump’s administration finalized a rule that expanded overtime pay eligibility to most salaried workers earning less than about $35,568, which it said made about 1.3 million more workers eligible for overtime pay. The Trump-era threshold is high enough to cover most line workers in lower-cost regions, Project 2025 said.

The Biden administration raised that threshold to $43,888 beginning July 1, and that will rise to $58,656 on Jan. 1, 2025. That would grant overtime eligibility to about 4 million workers, the Labor Department said.

It’s unclear how many workers Project 2025’s proposal to return to the Trump-era overtime threshold in some parts of the country would affect, but experts said some would presumably lose the right to overtime wages.

Other overtime proposals in Project 2025’s plan include allowing some workers to choose to accumulate paid time off instead of overtime pay, or to work more hours in one week and fewer in the next, rather than receive overtime.

Trump’s past with overtime pay is complicated. In 2016, the Obama administration said it would raise the overtime to salaried workers earning less than $47,476 a year, about double the exemption level set in 2004 of $23,660 a year.

But when a judge blocked the Obama rule, the Trump administration didn’t challenge the court ruling. Instead it set its own overtime threshold, which raised the amount, but by less than Obama.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Blog The Education Hub

https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2024/08/20/gcse-results-day-2024-number-grading-system/

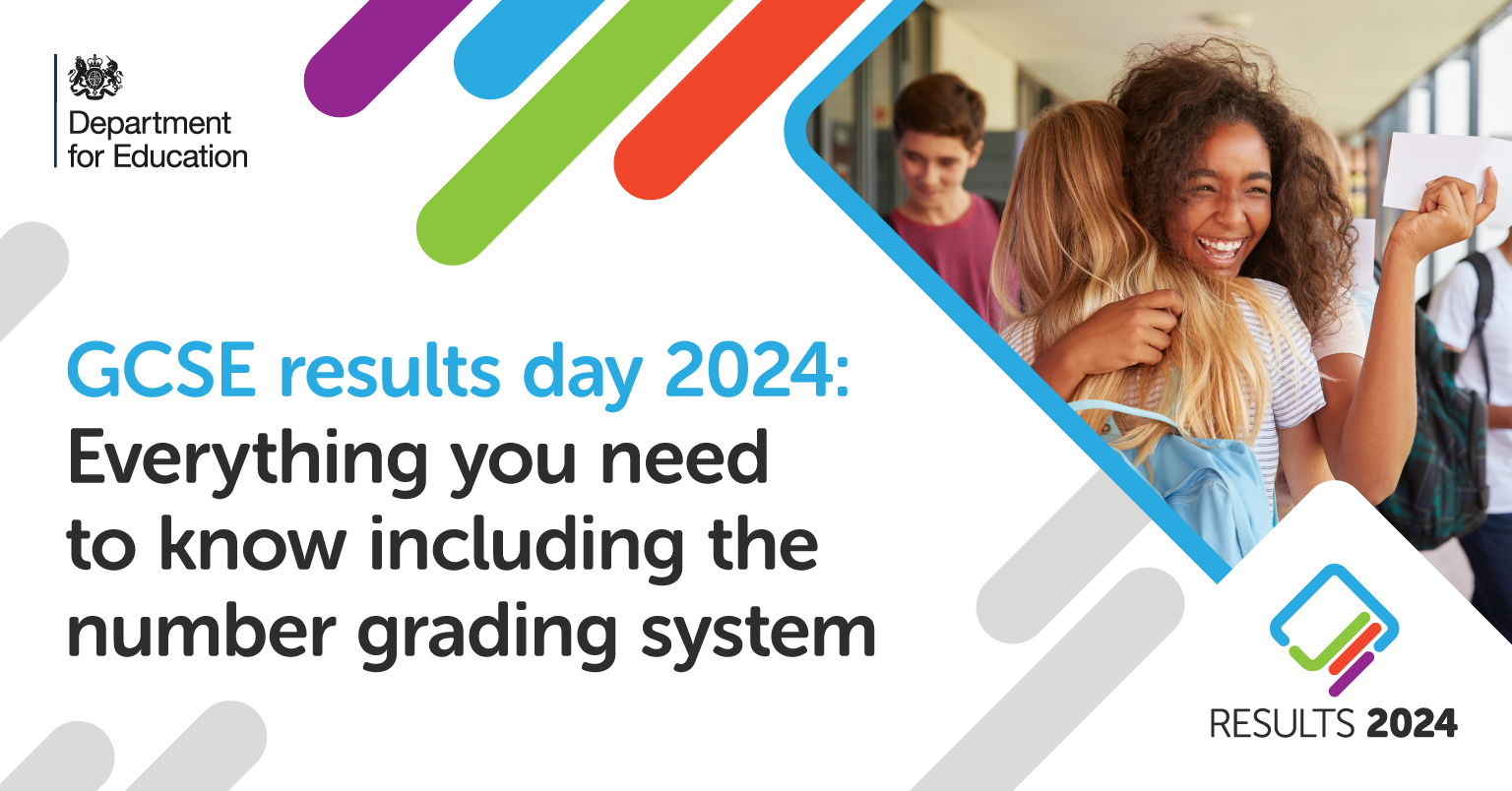

GCSE results day 2024: Everything you need to know including the number grading system

Thousands of students across the country will soon be finding out their GCSE results and thinking about the next steps in their education.

Here we explain everything you need to know about the big day, from when results day is, to the current 9-1 grading scale, to what your options are if your results aren’t what you’re expecting.

When is GCSE results day 2024?

GCSE results day will be taking place on Thursday the 22 August.

The results will be made available to schools on Wednesday and available to pick up from your school by 8am on Thursday morning.

Schools will issue their own instructions on how and when to collect your results.

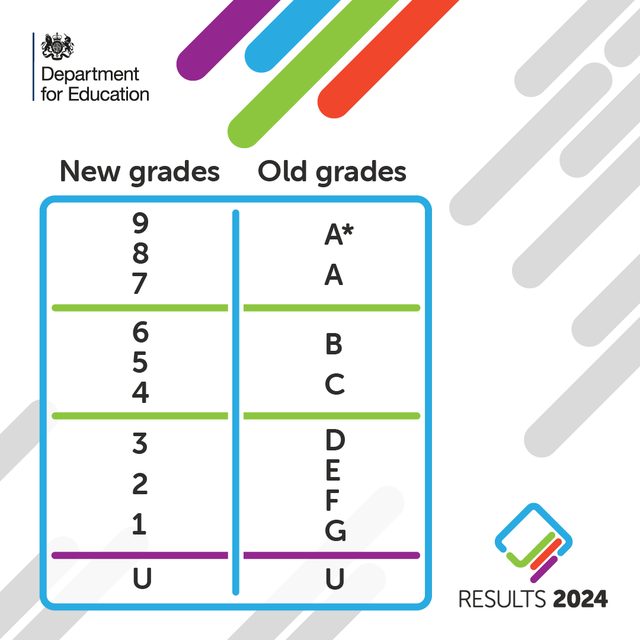

When did we change to a number grading scale?

The shift to the numerical grading system was introduced in England in 2017 firstly in English language, English literature, and maths.

By 2020 all subjects were shifted to number grades. This means anyone with GCSE results from 2017-2020 will have a combination of both letters and numbers.

The numerical grading system was to signal more challenging GCSEs and to better differentiate between students’ abilities - particularly at higher grades between the A *-C grades. There only used to be 4 grades between A* and C, now with the numerical grading scale there are 6.

What do the number grades mean?

The grades are ranked from 1, the lowest, to 9, the highest.

The grades don’t exactly translate, but the two grading scales meet at three points as illustrated below.

The bottom of grade 7 is aligned with the bottom of grade A, while the bottom of grade 4 is aligned to the bottom of grade C.

Meanwhile, the bottom of grade 1 is aligned to the bottom of grade G.

What to do if your results weren’t what you were expecting?

If your results weren’t what you were expecting, firstly don’t panic. You have options.

First things first, speak to your school or college – they could be flexible on entry requirements if you’ve just missed your grades.

They’ll also be able to give you the best tailored advice on whether re-sitting while studying for your next qualifications is a possibility.

If you’re really unhappy with your results you can enter to resit all GCSE subjects in summer 2025. You can also take autumn exams in GCSE English language and maths.

Speak to your sixth form or college to decide when it’s the best time for you to resit a GCSE exam.

Look for other courses with different grade requirements

Entry requirements vary depending on the college and course. Ask your school for advice, and call your college or another one in your area to see if there’s a space on a course you’re interested in.

Consider an apprenticeship

Apprenticeships combine a practical training job with study too. They’re open to you if you’re 16 or over, living in England, and not in full time education.

As an apprentice you’ll be a paid employee, have the opportunity to work alongside experienced staff, gain job-specific skills, and get time set aside for training and study related to your role.

You can find out more about how to apply here .

Talk to a National Careers Service (NCS) adviser

The National Career Service is a free resource that can help you with your career planning. Give them a call to discuss potential routes into higher education, further education, or the workplace.

Whatever your results, if you want to find out more about all your education and training options, as well as get practical advice about your exam results, visit the National Careers Service page and Skills for Careers to explore your study and work choices.

You may also be interested in:

- Results day 2024: What's next after picking up your A level, T level and VTQ results?

- When is results day 2024? GCSEs, A levels, T Levels and VTQs

Tags: GCSE grade equivalent , gcse number grades , GCSE results , gcse results day 2024 , gsce grades old and new , new gcse grades

Sharing and comments

Share this page, related content and links, about the education hub.

The Education Hub is a site for parents, pupils, education professionals and the media that captures all you need to know about the education system. You’ll find accessible, straightforward information on popular topics, Q&As, interviews, case studies, and more.

Please note that for media enquiries, journalists should call our central Newsdesk on 020 7783 8300. This media-only line operates from Monday to Friday, 8am to 7pm. Outside of these hours the number will divert to the duty media officer.

Members of the public should call our general enquiries line on 0370 000 2288.

Sign up and manage updates

Follow us on social media, search by date.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | ||

| 26 | 27 | 29 | 31 | |||

Comments and moderation policy

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

I Swore Off Air-Conditioning, and You Can, Too

By Stan Cox

Mr. Cox lives in Salina, Kan., and is the author of “Losing Our Cool: Uncomfortable Truths About Our Air-Conditioned World.”

Whenever people ask me how my wife and I have endured 25 Kansas summers almost entirely without air-conditioning, I like to say we do it because air-conditioning makes it too hot outside. We’re not ascetics, Luddites or misers; we just want to keep living comfortably, indoors and out.

It’s not just that air-conditioning is making our summers even hotter. (On a sweltering night in a city like Houston, the hot air that A.C. units blast out over the streets can raise outdoor temperatures up to three or four degrees.) It’s also that air-conditioning has altered the way most Americans experience heat.

Our bodies have grown so accustomed to climate-controlled indoor spaces, set at a chilly 69 degrees, that anything else can feel unbearable. And the greenhouse gases created by the roughly 90 percent of American households that own A.C. units mean that running them even in balmy temperatures is making the climate crisis worse.

Of course, I’m not suggesting that anyone switch the air off in the middle of a heat wave. Year in and year out, heat waves kill more people than any other type of natural disaster. If you live in Miami or Phoenix, you need air-conditioning to survive the summer. But if you live in the middle of the country, try leaving the air-conditioning off when it’s hot but not too hot.

Our species evolved, biologically and culturally, under wildly varying climatic conditions, and we haven’t lost that ability to adapt. Research suggests that when we spend more time in warm or hot summer weather, we can start feeling comfortable at temperatures that once felt insufferable. That’s the key to reducing dependence on air-conditioning: The less you use it, the easier it is to live without it.

When I was growing up in Georgia, my family moved into our first air-conditioned house when I was 12, and I loved it. But I left home for college in the 1970s, and I’ve lived mostly without A.C. ever since.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Switching Schools: Reconsidering the Relationship Between School Mobility and High School Dropout

Joseph gasper.

Westat, 1600 Research Blvd. Rockville, MD 20850, (240) 314-2485, (301) 610-4905

Stefanie DeLuca

JHU Department of Sociology, 532 Mergenthaler Hall, 3400. N. Charles St. Baltimore, MD 21218, (410) 516-7629, (410) 516-7590

Angela Estacion

JHU Department of Sociology, 533 Mergenthaler Hall, 3400. N. Charles St. Baltimore, MD 21218, (410) 516-7626, (410) 516-7590

Youth who switch schools are more likely to demonstrate a wide array of negative behavioral and educational outcomes, including dropping out of high school. However, whether switching schools actually puts youth at risk for dropout is uncertain, since youth who switch schools are similar to dropouts in their levels of prior school achievement and engagement, which suggests that switching schools may be part of the same long-term developmental process of disengagement that leads to dropping out. Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997, this study uses propensity score matching to pair youth who switched high schools with similar youth who stayed in the same school. We find that while over half the association between switching schools and dropout is explained by observed characteristics prior to 9 th grade, switching schools is still associated with dropout. Moreover, the relationship between switching schools and dropout varies depending on a youth's propensity for switching schools.

Graduating from high school is an important developmental task that marks the transition out of adolescence and into adulthood. However, recent statistics suggest that as few as two thirds of youth graduate within four years of entering high school, and that the odds of graduating from high school for black and Hispanic youth barely break 50/50 ( Greene & Winters, 2006 ; Miao & Haney, 2004 ; Swanson & Chaplin, 2003 ). 1 High school dropouts are likely to face a number of problems, both immediately after dropping out and later in life. Nearly one half of all high school dropouts ages 16 to 24 are jobless ( Sum et al., 2003 ), and high school dropouts earn about $9,245 less per year than high school graduates ( Doland, 2001 ). Additionally, nearly half of all heads of households on welfare ( Schwartz, 1995 ) and nearly two thirds of prison inmates have not received a high school diploma ( Harlow, 2003 ). Moreover, the costs of dropping out of high school and its associated ills fall not only on the individual high school dropout, but on the rest of society. It is estimated that the lifetime cost to the nation is $260,000 per dropout ( Rouse, 2005 ).

One factor that is believed to put youth at risk for dropping out of high school is switching schools for reasons other than promotion from one grade to the next, e.g., from elementary school to middle school or from middle school to high school ( Astone & McLanahan, 1994 ; Haveman, Wolfe, & Spaulding, 1991 ; Rumberger, 1995 ; Rumberger & Larson, 1998 ; South, Haynie, & Bose, 2007 ; Swanson & Schneider, 1999 ; Teachman, Paasch, & Carver, 1996 ). Indeed, switching schools is so strongly associated with dropping out that one study found that the majority of high school dropouts switched schools at least once, while the majority of high school graduates did not ( Rumberger & Larson, 1998 ). Moreover, the relationship between switching schools and high school dropout appears to be robust to controls for prior academic achievement and student background characteristics ( Rumberger & Larson, 1998 ; South, Haynie, & Bose, 2007 ).

However, whether switching schools actually causes students to dropout is uncertain. A few studies have documented that youth who switch schools resemble high school dropouts on several academic, family, and personal factors. Most notably, youth who switch schools are more likely to come from single parent families, are more disengaged, and perform worse academically than youth who do not switch schools, as evidenced by their higher rate of absenteeism, lower grades, and more frequent school suspension and delinquency ( Lee & Burkam, 1992 ; Rumberger & Larson, 1998 ). In addition, several studies that have examined the effects of switching schools on youth outcomes have found that much of the difference in achievement or problem behavior between youth who switch schools and those who do not disappears once socioeconomic background and prior achievement are taken into account ( Gasper, DeLuca, & Estacion, 2010 ; Pribesh & Downey, 1999 ; Temple & Reynolds, 1999 ). Taken together, these findings suggest that the apparent effects of school mobility on dropout may have little to do with school mobility and more to do with earlier school performance, family instability and other social or emotional factors. Since dropping out is thought to be the result of a long-term process of disengagement from school, one that begins as early as first grade ( Alexander, Entwisle, & Kabbani, 2001 ; Ensminger & Slusarcick, 1992 ; Finn, 1989 ), switching schools may simply be one point along a continuum of gradual withdrawal from school that ultimately ends with dropping out. It is therefore difficult to know whether mobility is a cause of dropout, or merely a symptom of the underlying process of disengagement that causes dropout.

The possibility that switching schools may be caused by the same cycle of disengagement that leads to dropout makes estimating the effect of switching schools on dropout a difficult task, due to selection bias. Since the factors that lead to dropout begin operating as early as first grade, youth who switch high schools are likely to be very different from youth who stay in the same high school in terms of their socioeconomic background, school performance, and behavior long before entering 9 th grade. The main challenge therefore lies in knowing the unobserved counterfactual outcome—would the same youth have dropped out if they had not switched schools? Without experimental data, treated youth (who switched schools) must be compared to untreated youth (who stayed in the same school) who are similar on all background factors predictive of dropping out (both observed and unobserved). Such comparisons would provide better estimates than prior research of the effect of switching schools on dropout.

It is also possible that the effect of a transition such as school mobility works differently across youth, depending on their initial risk (propensity) for changing schools. In other words, it is plausible that the youth most at risk for a non-promotional school change would be most affected by that change, as it becomes one more jolt to an already unstable set of family circumstances, a history of poor school performance, and a tendency toward problem behaviors. The literature on repeat residential mobility suggests that all of the disruptions in the lives of very poor youth have cumulative negative effects ( Shafft, 2006 ). At the other extreme, it is possible that youth who are the least likely to switch schools come from more stable and higher functioning families and have enough personal resources to weather the storm of a school change. For students in the middle of the risk continuum, a school change might be the event that pushes a student over the edge if he or she is ‘making it’ but coming from a fragile family or struggling socially. Therefore, we also consider the possibility that the effect of a school change varies by student's risk for experiencing the event.

In this study, we seek to determine whether switching high schools leads to dropping out, or whether high school mobility is simply a precursor to dropping out. To do this, we use data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), sponsored by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Designed to examine the educational and labor market experiences of youth, the NLSY97 contains richly descriptive information on youth's school enrollment, including the grade level of each school that a youth attended. In order to assess whether switching schools increases the likelihood of dropout, we use propensity score matching techniques to compare youth who switched high schools (switchers) with youth who stayed in the same high school (stayers) but who are similar on 177 characteristics measured before 9th grade. We consider a wide variety of background factors that may predispose youth to switching high schools or dropping out, including: demographics, socioeconomic background, family processes and dynamics, school performance and engagement, substance use and precocious transitions, and delinquency. By ensuring that youth who switched high schools are similar to youth who stayed in the same high school on all of these observed background characteristics, we can provide a better estimate than prior research of the relationship between switching schools and dropout. We then assess whether switching high schools has the same effect on youth who had a high propensity for switching compared to those with a low propensity. This allows us to determine whether switching schools leads to dropping out, and for which kinds of students.

Prior Research and Theory

Extent of school mobility.

While most youth do not experience much disruption in their school environments, a nontrivial number do end up changing schools outside of a normal promotion transition point (e.g. the transition from elementary to middle school at 6 th grade) (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2010). Over 30 percent of elementary school students make more than one school change between 1 st and 8 th grade ( Smith, 1995 ), and more than 25 percent of students make a non-promotional school change between grades 8 and 12 ( Rumberger & Larson, 1998 ). However, the extent to which students experience mobility varies closely with socioeconomic characteristics ( Hanushek, Kain, & Rivkin, 2004 ). For example, studies focusing on very poor minority families suggest that between sixty and seventy percent of these children change schools at least once in elementary grades and 20 percent change schools two or more times ( Temple & Reynolds, 1999 ).