Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

PhD Defence Process: A Comprehensive Guide

Embarking on the journey toward a PhD is an intellectual odyssey marked by tireless research, countless hours of contemplation, and a fervent commitment to contributing to the body of knowledge in one’s field. As the culmination of this formidable journey, the PhD defence stands as the final frontier, the proverbial bridge between student and scholar.

In this comprehensive guide, we unravel the intricacies of the PhD defence—a momentous occasion that is both a celebration of scholarly achievement and a rigorous evaluation of academic prowess. Join us as we explore the nuances of the defence process, addressing questions about its duration, contemplating the possibility of failure, and delving into the subtle distinctions of language that surround it.

Beyond the formalities, we aim to shed light on the significance of this rite of passage, dispelling misconceptions about its nature. Moreover, we’ll consider the impact of one’s attire on this critical day and share personal experiences and practical tips from those who have successfully navigated the defence journey.

Whether you are on the precipice of your own defence or are simply curious about the process, this guide seeks to demystify the PhD defence, providing a roadmap for success and a nuanced understanding of the pivotal event that marks the transition from student to scholar.

Introduction

A. definition and purpose:, b. overview of the oral examination:, a. general duration of a typical defense, b. factors influencing the duration:, c. preparation and flexibility:, a. preparation and thorough understanding of the research:, b. handling questions effectively:, c. confidence and composure during the presentation:, d. posture of continuous improvement:, a. exploring the possibility of failure:, b. common reasons for failure:, c. steps to mitigate the risk of failure:, d. post-failure resilience:, a. addressing the language variation:, b. conforming to regional preferences:, c. consistency in usage:, d. flexibility and adaptability:, e. navigating language in a globalized academic landscape:, a. debunking myths around the formality of the defense:, b. significance in validating research contributions:, c. post-defense impact:, a. appropriate attire for different settings:, b. professionalism and the impact of appearance:, c. practical tips for dressing success:, b. practical tips for a successful defense:, c. post-defense reflections:, career options after phd.

Embarking on the doctoral journey is a formidable undertaking, where aspiring scholars immerse themselves in the pursuit of knowledge, contributing new insights to their respective fields. At the pinnacle of this academic odyssey lies the PhD defence—a culmination that transcends the boundaries of a mere formality, symbolizing the transformation from a student of a discipline to a recognized contributor to the academic tapestry.

The PhD defence, also known as the viva voce or oral examination, is a pivotal moment in the life of a doctoral candidate.

PhD defence is not merely a ritualistic ceremony; rather, it serves as a platform for scholars to present, defend, and elucidate the findings and implications of their research. The defence is the crucible where ideas are tested, hypotheses scrutinized, and the depth of scholarly understanding is laid bare.

The importance of the PhD defence reverberates throughout the academic landscape. It is not just a capstone event; it is the juncture where academic rigour meets real-world application. The defence is the litmus test of a researcher’s ability to articulate, defend, and contextualize their work—an evaluation that extends beyond the pages of a dissertation.

Beyond its evaluative nature, the defence serves as a rite of passage, validating the years of dedication, perseverance, and intellectual rigour invested in the research endeavour. Success in the defence is a testament to the candidate’s mastery of their subject matter and the originality and impact of their contributions to the academic community.

Furthermore, a successful defence paves the way for future contributions, positioning the scholar as a recognized authority in their field. The defence is not just an endpoint; it is a launchpad, propelling researchers into the next phase of their academic journey as they continue to shape and redefine the boundaries of knowledge.

In essence, the PhD defence is more than a ceremonial checkpoint—it is a transformative experience that validates the intellectual journey, underscores the significance of scholarly contributions, and sets the stage for a continued legacy of academic excellence. As we navigate the intricacies of this process, we invite you to explore the multifaceted dimensions that make the PhD defence an indispensable chapter in the narrative of academic achievement.

What is a PhD Defence?

At its core, a PhD defence is a rigorous and comprehensive examination that marks the culmination of a doctoral candidate’s research journey. It is an essential component of the doctoral process in which the candidate is required to defend their dissertation before a committee of experts in the field. The defence serves multiple purposes, acting as both a showcase of the candidate’s work and an evaluative measure of their understanding, critical thinking, and contributions to the academic domain.

The primary goals of a PhD defence include:

- Presentation of Research: The candidate presents the key findings, methodology, and significance of their research.

- Demonstration of Mastery: The defence assesses the candidate’s depth of understanding, mastery of the subject matter, and ability to engage in scholarly discourse.

- Critical Examination: Committee members rigorously question the candidate, challenging assumptions, testing methodologies, and probing the boundaries of the research.

- Validation of Originality: The defence validates the originality and contribution of the candidate’s work to the existing body of knowledge.

The PhD defence often takes the form of an oral examination, commonly referred to as the viva voce. This oral component adds a dynamic and interactive dimension to the evaluation process. Key elements of the oral examination include:

- Presentation: The candidate typically begins with a formal presentation, summarizing the dissertation’s main components, methodology, and findings. This presentation is an opportunity to showcase the significance and novelty of the research.

- Questioning and Discussion: Following the presentation, the candidate engages in a thorough questioning session with the examination committee. Committee members explore various aspects of the research, challenging the candidates to articulate their rationale, defend their conclusions, and respond to critiques.

- Defence of Methodology: The candidate is often required to defend the chosen research methodology, demonstrating its appropriateness, rigour, and contribution to the field.

- Evaluation of Contributions: Committee members assess the originality and impact of the candidate’s contributions to the academic discipline, seeking to understand how the research advances existing knowledge.

The oral examination is not a mere formality; it is a dynamic exchange that tests the candidate’s intellectual acumen, research skills, and capacity to contribute meaningfully to the scholarly community.

In essence, the PhD defence is a comprehensive and interactive evaluation that encapsulates the essence of a candidate’s research journey, demanding a synthesis of knowledge, clarity of expression, and the ability to navigate the complexities of academic inquiry. As we delve into the specifics of the defence process, we will unravel the layers of preparation and skill required to navigate this transformative academic milestone.

How Long is a PhD Defence?

The duration of a PhD defence can vary widely, but it typically ranges from two to three hours. This time frame encompasses the candidate’s presentation of their research, questioning and discussions with the examination committee, and any additional deliberations or decisions by the committee. However, it’s essential to note that this is a general guideline, and actual defence durations may vary based on numerous factors.

- Sciences and Engineering: Defenses in these fields might lean towards the shorter end of the spectrum, often around two hours. The focus is often on the methodology, results, and technical aspects.

- Humanities and Social Sciences: Given the theoretical and interpretive nature of research in these fields, defences might extend closer to three hours or more. Discussions may delve into philosophical underpinnings and nuanced interpretations.

- Simple vs. Complex Studies: The complexity of the research itself plays a role. Elaborate experiments, extensive datasets, or intricate theoretical frameworks may necessitate a more extended defence.

- Number of Committee Members: A larger committee or one with diverse expertise may lead to more extensive discussions and varied perspectives, potentially elongating the defence.

- Committee Engagement: The level of engagement and probing by committee members can influence the overall duration. In-depth discussions or debates may extend the defence time.

- Cultural Norms: In some countries, the oral defence might be more ceremonial, with less emphasis on intense questioning. In others, a rigorous and extended defence might be the norm.

- Evaluation Practices: Different academic systems have varying evaluation criteria, which can impact the duration of the defence.

- Institutional Guidelines: Some institutions may have specific guidelines on defence durations, influencing the overall time allotted for the process.

Candidates should be well-prepared for a defence of any duration. Adequate preparation not only involves a concise presentation of the research but also anticipates potential questions and engages in thoughtful discussions. Additionally, candidates should be flexible and responsive to the dynamics of the defense, adapting to the pace set by the committee.

Success Factors in a PhD Defence

- Successful defence begins with a deep and comprehensive understanding of the research. Candidates should be well-versed in every aspect of their study, from the theoretical framework to the methodology and findings.

- Thorough preparation involves anticipating potential questions from the examination committee. Candidates should consider the strengths and limitations of their research and be ready to address queries related to methodology, data analysis, and theoretical underpinnings.

- Conducting mock defences with peers or mentors can be invaluable. It helps refine the presentation, exposes potential areas of weakness, and provides an opportunity to practice responding to challenging questions.

- Actively listen to questions without interruption. Understanding the nuances of each question is crucial for providing precise and relevant responses.

- Responses should be clear, concise, and directly address the question. Avoid unnecessary jargon, and strive to convey complex concepts in a manner that is accessible to the entire committee.

- It’s acceptable not to have all the answers. If faced with a question that stumps you, acknowledge it honestly. Expressing a willingness to explore the topic further demonstrates intellectual humility.

- Use questions as opportunities to reinforce key messages from the research. Skillfully link responses back to the core contributions of the study, emphasizing its significance.

- Rehearse the presentation multiple times to build familiarity with the material. This enhances confidence, reduces nervousness, and ensures a smooth and engaging delivery.

- Maintain confident and open body language. Stand tall, make eye contact, and use gestures judiciously. A composed demeanour contributes to a positive impression.

- Acknowledge and manage nervousness. It’s natural to feel some anxiety, but channelling that energy into enthusiasm for presenting your research can turn nervousness into a positive force.

- Engage with the committee through a dynamic and interactive presentation. Invite questions during the presentation to create a more conversational atmosphere.

- Utilize visual aids effectively. Slides or other visual elements should complement the spoken presentation, reinforcing key points without overwhelming the audience.

- View the defence not only as an evaluation but also as an opportunity for continuous improvement. Feedback received during the defence can inform future research endeavours and scholarly pursuits.

In essence, success in a PhD defence hinges on meticulous preparation, adept handling of questions, and projecting confidence and composure during the presentation. A well-prepared and resilient candidate is better positioned to navigate the challenges of the defence, transforming it from a moment of evaluation into an affirmation of scholarly achievement.

Failure in PhD Defence

- While the prospect of failing a PhD defence is relatively rare, it’s essential for candidates to acknowledge that the possibility exists. Understanding this reality can motivate diligent preparation and a proactive approach to mitigate potential risks.

- Failure, if it occurs, should be seen as a learning opportunity rather than a definitive endpoint. It may highlight areas for improvement and offer insights into refining the research and presentation.

- Lack of thorough preparation, including a weak grasp of the research content, inadequate rehearsal, and failure to anticipate potential questions, can contribute to failure.

- Inability to effectively defend the chosen research methodology, including justifying its appropriateness and demonstrating its rigour, can be a critical factor.

- Failing to clearly articulate the original contributions of the research and its significance to the field may lead to a negative assessment.

- Responding defensively to questions, exhibiting a lack of openness to critique, or being unwilling to acknowledge limitations can impact the overall impression.

- Inability to address committee concerns or incorporate constructive feedback received during the defense may contribute to a negative outcome.

- Comprehensive preparation is the cornerstone of success. Candidates should dedicate ample time to understanding every facet of their research, conducting mock defences, and seeking feedback.

- Identify potential weaknesses in the research and address them proactively. Being aware of limitations and articulating plans for addressing them in future work demonstrates foresight.

- Engage with mentors, peers, or advisors before the defence. Solicit constructive feedback on both the content and delivery of the presentation to refine and strengthen the defence.

- Develop strategies to manage stress and nervousness. Techniques such as mindfulness, deep breathing, or visualization can be effective in maintaining composure during the defence.

- Conduct a pre-defense review of all materials, ensuring that the presentation aligns with the dissertation and that visual aids are clear and supportive.

- Approach the defence with an open and reflective attitude. Embrace critique as an opportunity for improvement rather than as a personal affront.

- Clarify expectations with the examination committee beforehand. Understanding the committee’s focus areas and preferences can guide preparation efforts.

- In the event of failure, candidates should approach the situation with resilience. Seek feedback from the committee, understand the reasons for the outcome, and use the experience as a springboard for improvement.

In summary, while the prospect of failing a PhD defence is uncommon, acknowledging its possibility and taking proactive steps to mitigate risks are crucial elements of a well-rounded defence strategy. By addressing common failure factors through thorough preparation, openness to critique, and a resilient attitude, candidates can increase their chances of a successful defence outcome.

PhD Defense or Defence?

- The choice between “defense” and “defence” is primarily a matter of British English versus American English spelling conventions. “Defense” is the preferred spelling in American English, while “defence” is the British English spelling.

- In the global academic community, both spellings are generally understood and accepted. However, the choice of spelling may be influenced by the academic institution’s language conventions or the preferences of individual scholars.

- Academic institutions may have specific guidelines regarding language conventions, and candidates are often expected to adhere to the institution’s preferred spelling.

- Candidates may also consider the preferences of their advisors or committee members. If there is a consistent spelling convention used within the academic department, it is advisable to align with those preferences.

- Consideration should be given to the spelling conventions of scholarly journals in the candidate’s field. If intending to publish research stemming from the dissertation, aligning with the conventions of target journals is prudent.

- If the defense presentation or dissertation will be shared with an international audience, using a more universally recognized spelling (such as “defense”) may be preferred to ensure clarity and accessibility.

- Regardless of the chosen spelling, it’s crucial to maintain consistency throughout the document. Mixing spellings can distract from the content and may be perceived as an oversight.

- In oral presentations and written correspondence related to the defence, including emails, it’s advisable to maintain consistency with the chosen spelling to present a professional and polished image.

- Recognizing that language conventions can vary, candidates should approach the choice of spelling with flexibility. Being adaptable to the preferences of the academic context and demonstrating an awareness of regional variations reflects a nuanced understanding of language usage.

- With the increasing globalization of academia, an awareness of language variations becomes essential. Scholars often collaborate across borders, and an inclusive approach to language conventions contributes to effective communication and collaboration.

In summary, the choice between “PhD defense” and “PhD defence” boils down to regional language conventions and institutional preferences. Maintaining consistency, being mindful of the target audience, and adapting to the expectations of the academic community contribute to a polished and professional presentation, whether in written documents or oral defences.

Is PhD Defense a Formality?

- While the PhD defence is a structured and ritualistic event, it is far from being a mere formality. It is a critical and substantive part of the doctoral journey, designed to rigorously evaluate the candidate’s research contributions, understanding of the field, and ability to engage in scholarly discourse.

- The defence is not a checkbox to be marked but rather a dynamic process where the candidate’s research is evaluated for its scholarly merit. The committee scrutinizes the originality, significance, and methodology of the research, aiming to ensure it meets the standards of advanced academic work.

- Far from a passive or purely ceremonial event, the defence involves active engagement between the candidate and the examination committee. Questions, discussions, and debates are integral components that enrich the scholarly exchange during the defence.

- The defence serves as a platform for the candidate to demonstrate the originality of their research. Committee members assess the novelty of the contributions, ensuring that the work adds value to the existing body of knowledge.

- Beyond the content, the defence evaluates the methodological rigour of the research. Committee members assess whether the chosen methodology is appropriate, well-executed, and contributes to the validity of the findings.

- Successful completion of the defence affirms the candidate’s ability to contribute meaningfully to the academic discourse in their field. It is an endorsement of the candidate’s position as a knowledgeable and respected scholar.

- The defence process acts as a quality assurance mechanism in academia. It ensures that individuals awarded a doctoral degree have undergone a thorough and rigorous evaluation, upholding the standards of excellence in research and scholarly inquiry.

- Institutions have specific criteria and standards for awarding a PhD. The defence process aligns with these institutional and academic standards, providing a consistent and transparent mechanism for evaluating candidates.

- Successful completion of the defence is a pivotal moment that marks the transition from a doctoral candidate to a recognized scholar. It opens doors to further contributions, collaborations, and opportunities within the academic community.

- Research presented during the defence often forms the basis for future publications. The validation received in the defence enhances the credibility of the research, facilitating its dissemination and impact within the academic community.

- Beyond the academic realm, a successfully defended PhD is a key credential for professional advancement. It enhances one’s standing in the broader professional landscape, opening doors to research positions, teaching opportunities, and leadership roles.

In essence, the PhD defence is a rigorous and meaningful process that goes beyond formalities, playing a crucial role in affirming the academic merit of a candidate’s research and marking the culmination of their journey toward scholarly recognition.

Dressing for Success: PhD Defense Outfit

- For Men: A well-fitted suit in neutral colours (black, navy, grey), a collared dress shirt, a tie, and formal dress shoes.

- For Women: A tailored suit, a blouse or button-down shirt, and closed-toe dress shoes.

- Dress codes can vary based on cultural expectations. It’s advisable to be aware of any cultural nuances within the academic institution and to adapt attire accordingly.

- With the rise of virtual defenses, considerations for attire remain relevant. Even in online settings, dressing professionally contributes to a polished and serious demeanor. Virtual attire can mirror what one would wear in-person, focusing on the upper body visible on camera.

- The attire chosen for a PhD defense contributes to the first impression that a candidate makes on the examination committee. A professional and polished appearance sets a positive tone for the defense.

- Dressing appropriately reflects respect for the gravity of the occasion. It acknowledges the significance of the defense as a formal evaluation of one’s scholarly contributions.

- Wearing professional attire can contribute to a boost in confidence. When individuals feel well-dressed and put-together, it can positively impact their mindset and overall presentation.

- The PhD defense is a serious academic event, and dressing professionally fosters an atmosphere of seriousness and commitment to the scholarly process. It aligns with the respect one accords to academic traditions.

- Institutional norms may influence dress expectations. Some academic institutions may have specific guidelines regarding attire for formal events, and candidates should be aware of and adhere to these norms.

- While adhering to the formality expected in academic settings, individuals can also express their personal style within the bounds of professionalism. It’s about finding a balance between institutional expectations and personal comfort.

- Select and prepare the outfit well in advance to avoid last-minute stress. Ensure that the attire is clean, well-ironed, and in good condition.

- Accessories such as ties, scarves, or jewelry should complement the outfit. However, it’s advisable to keep accessories subtle to maintain a professional appearance.

- While dressing professionally, prioritize comfort. PhD defenses can be mentally demanding, and comfortable attire can contribute to a more confident and composed demeanor.

- Pay attention to grooming, including personal hygiene and haircare. A well-groomed appearance contributes to an overall polished look.

- Start preparation well in advance of the defense date. Know your research inside out, anticipate potential questions, and be ready to discuss the nuances of your methodology, findings, and contributions.

- Conduct mock defenses with peers, mentors, or colleagues. Mock defenses provide an opportunity to receive constructive feedback, practice responses to potential questions, and refine your presentation.

- Strike a balance between confidence and humility. Confidence in presenting your research is essential, but being open to acknowledging limitations and areas for improvement demonstrates intellectual honesty.

- Actively engage with the examination committee during the defense. Listen carefully to questions, respond thoughtfully, and view the defense as a scholarly exchange rather than a mere formality.

- Understand the expertise and backgrounds of the committee members. Tailor your presentation and responses to align with the interests and expectations of your specific audience.

- Practice time management during your presentation. Ensure that you allocate sufficient time to cover key aspects of your research, leaving ample time for questions and discussions.

- It’s normal to feel nervous, but practicing mindfulness and staying calm under pressure is crucial. Take deep breaths, maintain eye contact, and focus on delivering a clear and composed presentation.

- Have a plan for post-defense activities. Whether it’s revisions to the dissertation, publications, or future research endeavors, having a roadmap for what comes next demonstrates foresight and commitment to ongoing scholarly contributions.

- After successfully defending, individuals often emphasize the importance of taking time to reflect on the entire doctoral journey. Acknowledge personal and academic growth, celebrate achievements, and use the experience to inform future scholarly pursuits.

In summary, learning from the experiences of others who have successfully defended offers a wealth of practical wisdom. These insights, combined with thoughtful preparation and a proactive approach, contribute to a successful and fulfilling defense experience.

You have plenty of career options after completing a PhD. For more details, visit my blog posts:

7 Essential Steps for Building a Robust Research Portfolio

Exciting Career Opportunities for PhD Researchers and Research Scholars

Freelance Writing or Editing Opportunities for Researchers A Comprehensive Guide

Research Consultancy: An Alternate Career for Researchers

The Insider’s Guide to Becoming a Patent Agent: Opportunities, Requirements, and Challenges

The journey from a curious researcher to a recognized scholar culminates in the PhD defence—an intellectual odyssey marked by dedication, resilience, and a relentless pursuit of knowledge. As we navigate the intricacies of this pivotal event, it becomes evident that the PhD defence is far more than a ceremonial rite; it is a substantive evaluation that validates the contributions of a researcher to the academic landscape.

Upcoming Events

- Visit the Upcoming International Conferences at Exotic Travel Destinations with Travel Plan

- Visit for Research Internships Worldwide

Recent Posts

- Best 5 Journals for Quick Review and High Impact in August 2024

- 05 Quick Review, High Impact, Best Research Journals for Submissions for July 2024

- Top Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Research Paper

- Average Stipend for Research/Academic Internships

- These Institutes Offer Remote Research/Academic Internships

- All Blog Posts

- Research Career

- Research Conference

- Research Internship

- Research Journal

- Research Tools

- Uncategorized

- Research Conferences

- Research Journals

- Research Grants

- Internships

- Research Internships

- Email Templates

- Conferences

- Blog Partners

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2024 Research Voyage

Design by ThemesDNA.com

- Scholar's Toolbox

What? Why? How? A list of potential PhD defense questions

In August 2020, I defended my PhD successfully. In the preceding months, I had generated a list of potential defense questions by using various different sources (websites, other defenses I watched, colleagues, and my supervisors). The list ended up helping me a lot. Today I shared this list with a colleague who is soon defending, and I thought: Why not share it publicly?

Note: The questions were compiled with a Finnish PhD defense in mind. In Finland, the defense is at the very end of the research process, and no changes to the PhD will be made after the event. The defense is also a public event.

The list was last edited: November 3rd, 2022

Title and cover.

- Why did you choose this title? Were there any other kinds of titles you were considering?

- Why did you choose this photo/image as your thesis cover? (if there is one)

Topic and contribution to the field

- Why did you choose this research topic?

- Why do you think this topic is important? For whom is it important?

- What do you think your work has added to the discipline/field/study of this topic?

- How is your study original?

- [Your topic] seems to be something that is usually studied discipline X. However, your thesis represents discipline Y. How did you navigate the interdisciplinarity of your work?

Paradigm/theory/concepts

- How did you decide to use this particular conceptual/theoretical framework?

- How did your chosen framework help you to explore your research problem?

- How would someone using another theoretical framework interpret your results?

- What are the shortcomings of this particular theory/conceptual framework?

- How would you describe/define/summarise … [insert a term]

- In your work, you introduce a new concept/theory. Why did you decide to do that instead of using an existing concept/theory?

- Could you describe your theoretical/methodological framework in a way that the audience also understands it? (for public defenses)

Literature review

- Why did your literature review cover these areas but not others?

- The literature review looks very tidy – doesn’t anything challenge it?

- Why did you (not) include the work by X in your study?

- Which scholar(s) have you been influenced by the most?

Research question(s)

- How did you come to formulate this particular research question / these research questions?

- How did your research questions/problem changed during the research process?

- Were there research questions you decided to add/remove during the research process?

- Why don’t you have a research question?

- How did you decide to use these particular methods of data collection/analysis? Were there other options you considered?

- Why did you choose quantitative/qualitative/mixed methods approach?

- What informed your choice of methods?

- What are the advantages/disadvantages of the chosen methods?

- How did you select your participants/this particular data?

- Describe how you generated your data.

- Why did you analyse your data in this way? What other ways were there available? Why didn’t you choose those methods?

- If you could still improve this measure/procedure/etc., how would you do it?

- How would you explain the low/high response rate of your survey?

- How did you triangulate your data?

- If you could do your study all over again with unlimited resources, how would you do it?

- How do you explain the discrepancy between your findings and the findings of previous studies?

- Did you expect these kinds of results? Why (not)?

- What is the most important result of your work?

- Who should care about your work and the results?

- How generalizable are your findings and why?

- Were there any other ways to present your results?

- Based on your findings, how would you develop [your topic]?

- What is common or different to these substudies included in your dissertation?

- What did [your approach] reveal that other approaches could not have reveal?

- What did you not see because you did your work [in this way]?

- How could [x] now be rethought in the light of COVID-19?

- What kinds of implications do your results have for further research/practice/policy?

Research process

- How did your own position/background/bias affect your research?

- Describe your researcher positionality.

- What were the biggest challenges during the research process?

- Were there any surprises during your research, pleasant or unpleasant?

- What was the most interesting part of your work?

- How did you address research ethics during your research?

- What implications do your findings have for [your topic]?

- What do you see as the problems in your study? What limitations do these impose on what you can say? How would you address these limitations in future studies?

- What could you not study in the end? Why?

- What kind of a dissertation did you want to do originally? Why did your plans change?

- If you could now redo the work, what would you differently?

- Is there anything else that you would like to tell us about your thesis which you have not had the opportunity to tell us during the defense?

Future research

- What do you plan to do next with your data?

- What would be the next logical study to do as a follow-up to this one?

- What will you study next?

- How does gaining a doctorate advance your career plans?

Photo by Vadim Bogulov on Unsplash

Leave a reply cancel reply.

- Scholar’s Toolbox

- In the Spotlight

- Working in Academia

- Miscellanea

- Contributors

- About ECHER

Defending Your Dissertation: A Guide

Written by Luke Wink-Moran | Photo by insta_photos

Dissertation defenses are daunting, and no wonder; it’s not a “dissertation discussion,” or a “dissertation dialogue.” The name alone implies that the dissertation you’ve spent the last x number of years working on is subject to attack. And if you don’t feel trepidation for semantic reasons, you might be nervous because you don’t know what to expect. Our imaginations are great at making The Unknown scarier than reality. The good news is that you’ll find in this newsletter article experts who can shed light on what dissertations defenses are really like, and what you can do to prepare for them.

The first thing you should know is that your defense has already begun. It started the minute you began working on your dissertation— maybe even in some of the classes you took beforehand that helped you formulate your ideas. This, according to Dr. Celeste Atkins, is why it’s so important to identify a good mentor early in graduate school.

“To me,” noted Dr. Atkins, who wrote her dissertation on how sociology faculty from traditionally marginalized backgrounds teach about privilege and inequality, “the most important part of the doctoral journey was finding an advisor who understood and supported what I wanted from my education and who was willing to challenge me and push me, while not delaying me. I would encourage future PhDs to really take the time to get to know the faculty before choosing an advisor and to make sure that the members of their committee work well together.”

Your advisor will be the one who helps you refine arguments and strengthen your work so that by the time it reaches your dissertation committee, it’s ready. Next comes the writing process, which many students have said was the hardest part of their PhD. I’ve included this section on the writing process because this is where you’ll create all the material you’ll present during your defense, so it’s important to navigate it successfully. The writing process is intellectually grueling, it eats time and energy, and it’s where many students find themselves paddling frantically to avoid languishing in the “All-But-Dissertation” doldrums. The writing process is also likely to encroach on other parts of your life. For instance, Dr. Cynthia Trejo wrote her dissertation on college preparation for Latin American students while caring for a twelve-year-old, two adult children, and her aging parents—in the middle of a pandemic. When I asked Dr. Trejo how she did this, she replied:

“I don’t take the privilege of education for granted. My son knew I got up at 4:00 a.m. every morning, even on weekends, even on holidays; and it’s a blessing that he’s seen that work ethic and that dedication and the end result.”

Importantly, Dr. Trejo also exercised regularly and joined several online writing groups at UArizona. She mobilized her support network— her partner, parents, and even friends from high school to help care for her son.

The challenges you face during the writing process can vary by discipline. Jessika Iwanski is an MD/PhD student who in 2022 defended her dissertation on genetic mutations in sarcomeric proteins that lead to severe, neonatal dilated cardiomyopathy. She described her writing experience as “an intricate process of balancing many things at once with a deadline (defense day) that seems to be creeping up faster and faster— finishing up experiments, drafting the dissertation, preparing your presentation, filling out all the necessary documents for your defense and also, for MD/PhD students, beginning to reintegrate into the clinical world (reviewing your clinical knowledge and skill sets)!”

But no matter what your unique challenges are, writing a dissertation can take a toll on your mental health. Almost every student I spoke with said they saw a therapist and found their sessions enormously helpful. They also looked to the people in their lives for support. Dr. Betsy Labiner, who wrote her dissertation on Interiority, Truth, and Violence in Early Modern Drama, recommended, “Keep your loved ones close! This is so hard – the dissertation lends itself to isolation, especially in the final stages. Plus, a huge number of your family and friends simply won’t understand what you’re going through. But they love you and want to help and are great for getting you out of your head and into a space where you can enjoy life even when you feel like your dissertation is a flaming heap of trash.”

While you might sometimes feel like your dissertation is a flaming heap of trash, remember: a) no it’s not, you brilliant scholar, and b) the best dissertations aren’t necessarily perfect dissertations. According to Dr. Trejo, “The best dissertation is a done dissertation.” So don’t get hung up on perfecting every detail of your work. Think of your dissertation as a long-form assignment that you need to finish in order to move onto the next stage of your career. Many students continue revising after graduation and submit their work for publication or other professional objectives.

When you do finish writing your dissertation, it’s time to schedule your defense and invite friends and family to the part of the exam that’s open to the public. When that moment comes, how do you prepare to present your work and field questions about it?

“I reread my dissertation in full in one sitting,” said Dr. Labiner. “During all my time writing it, I’d never read more than one complete chapter at a time! It was a huge confidence boost to read my work in full and realize that I had produced a compelling, engaging, original argument.”

There are many other ways to prepare: create presentation slides and practice presenting them to friends or alone; think of questions you might be asked and answer them; think about what you want to wear or where you might want to sit (if you’re presenting on Zoom) that might give you a confidence boost. Iwanksi practiced presenting with her mentor and reviewed current papers to anticipate what questions her committee might ask. If you want to really get in the zone, you can emulate Dr. Labiner and do a full dress rehearsal on Zoom the day before your defense.

But no matter what you do, you’ll still be nervous:

“I had a sense of the logistics, the timing, and so on, but I didn’t really have clear expectations outside of the structure. It was a sort of nebulous three hours in which I expected to be nauseatingly terrified,” recalled Dr. Labiner.

“I expected it to be terrifying, with lots of difficult questions and constructive criticism/comments given,” agreed Iwanski.

“I expected it to be very scary,” said Dr. Trejo.

“I expected it to be like I was on trial, and I’d have to defend myself and prove I deserved a PhD,” said Dr Atkins.

And, eventually, inexorably, it will be time to present.

“It was actually very enjoyable” said Iwanski. “It was more of a celebration of years of work put into this project—not only by me but by my mentor, colleagues, lab members and collaborators! I felt very supported by all my committee members and, rather than it being a rapid fire of questions, it was more of a scientific discussion amongst colleagues who are passionate about heart disease and muscle biology.”

“I was anxious right when I logged on to the Zoom call for it,” said Dr. Labiner, “but I was blown away by the number of family and friends that showed up to support me. I had invited a lot of people who I didn’t at all think would come, but every single person I invited was there! Having about 40 guests – many of them joining from different states and several from different countries! – made me feel so loved and celebrated that my nerves were steadied very quickly. It also helped me go into ‘teaching mode’ about my work, so it felt like getting to lead a seminar on my most favorite literature.”

“In reality, my dissertation defense was similar to presenting at an academic conference,” said Dr. Atkins. “I went over my research in a practiced and organized way, and I fielded questions from the audience.

“It was a celebration and an important benchmark for me,” said Dr. Trejo. “It was a pretty happy day. Like the punctuation at the end of your sentence: this sentence is done; this journey is done. You can start the next sentence.”

If you want to learn more about dissertations in your own discipline, don’t hesitate to reach out to graduates from your program and ask them about their experiences. If you’d like to avail yourself of some of the resources that helped students in this article while they wrote and defended their dissertations, check out these links:

The Graduate Writing Lab

https://thinktank.arizona.edu/writing-center/graduate-writing-lab

The Writing Skills Improvement Program

https://wsip.arizona.edu

Campus Health Counseling and Psych Services

https://caps.arizona.edu

https://www.scribbr.com/

Tips for preparing your PhD defense [EASY dissertation defense]

Embarking on the final hurdle of your doctoral journey, the PhD dissertation defense, can feel daunting.

This significant event involves presenting and justifying years of research to a committee of field experts, showcasing your comprehension, originality, and critical thinking skills.

With various expectations from committee members, it’s crucial to know what makes a compelling thesis and how to adeptly defend your arguments. Preparation is key; from choosing well-suited examiners to meticulously preparing for potential questions, every step counts.

This article provides easy-to-follow tips for this process, from how to approach revisions to the actual defense duration, ensuring a smoother dissertation defense.

Top tips for your PhD defence process

- Understand Expectations : Understand what your examiners are looking for in your thesis. They expect it to be relevant to the field, have a clear title, a comprehensive abstract, engage with relevant literature, answer clear research questions, provide a consistent argument, and make a significant contribution to knowledge. They also value the ability to show connections between different parts of the thesis and a confident, positive attitude during the defense.

- Choose the Right Examiners : Make strategic decisions when selecting your examiners. They should be experts in your field, open-minded about cross-discipline work, cited in your work, have a constructive approach, align with your methodology, and respect critical viewpoints. Consider your supervisor’s advice, as they can help identify suitable examiners.

- Thorough Preparation : Understand your institute’s specific defense requirements and practice rigorously. Break down your thesis into sections, time your presentation, focus on key points, and prepare for potential questions. Consider setting up a mock defense to familiarize yourself with the process.

- Master Your Content : Understand your work inside out. Rather than cramming as much information as possible, focus on thoroughly comprehending your research. If faced with an unexpected question during the defense, take a moment to formulate an organized response.

- Manage Your Time : Be aware that dissertation defenses usually last between one to three hours, so ensure your presentation fits within this timeframe. Remember, the defense is an opportunity to showcase your hard work. Be confident and composed throughout the process.

What Is Dissertation Defense?

A PhD defense, also known as a viva , is a critical process that marks the completion of a doctoral degree. It varies from one institution to another and between different countries.

It could be a private examination by a panel of experts in the field or a public defense before an audience.

In this defense, you present and justify the research you have conducted over many years.

You’ll engage in a rigorous academic conversation about the different aspects of your research, answer questions, and explain your findings and their implications.

The defense is a chance for the panel to test your comprehension of your chosen subject area, your work’s originality, and its contribution to the field. It also tests your ability to think critically, to articulate your thoughts, and how effectively you can defend your arguments under pressure.

The essence of a PhD defense is not only to assess the validity of the thesis but also to assess the candidate’s proficiency in their subject.

What Are the Expectations of PhD Defence Examiners? Understand your dissertation committee.

Meeting the expectations of committee members in the context of a dissertation is essential for the successful completion of the research.

They will have read your thesis and will be looking for any mistakes or areas that they are unsure about to ask you during your PhD defence.

Here are what PhD defence examiners are looking for in your thesis and may have questions at your oral defence:

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Relevance to Field | The thesis must be clearly relevant to the specific academic field. |

| Clear Title | The thesis should have a clear, descriptive, and concise title. |

| Clear Abstract | The abstract should provide a good overview of the research and its findings. |

| Relevant Literature Review | The thesis should engage with the existing academic literature relevant to the research topic. |

| Research Questions | Research questions should be clear, relevant, and answered in the course of the research. |

| Consistent Argument | The thesis should contain a clear and consistent argument throughout. |

| Conceptual Conclusions | The conclusions should not only summarize the research findings but also relate back to the literature review and conceptual issues raised. |

| Contribution to Knowledge | The thesis should make a significant contribution to the field of knowledge. |

| Ability to think interconnectedly | The ability to show connections between different parts of the thesis is important, as it demonstrates a higher level of thinking. |

| Pleasurable Text | The text should be enjoyable to read, well-written, and explicit in terms of ideas and concepts. |

| Positive Attitude | The candidate should demonstrate confidence, enjoyment, and a positive attitude during the Viva (oral examination), symbolized by smiling with the examiners, not at them. |

| Display of interconnectedness | The thesis should clearly show how various parts are interconnected, ultimately achieving synergy. |

A dissertation committee typically consists of external experts (in a similar field) who will engage in robust discussion about your PhD and submitted thesis.

As committee members, their primary role is to actively engage with the dissertation research, offering constructive feedback and suggestions as well as deciding if you have satisfied the requirements of the university to be awarded a PhD

Here’s my video about the common questions you’ll likely encounter during your defence and how you can answer them:

How to Choose your PhD examiners and committee members

Choosing your PhD examiners requires strategic thinking and insightful conversations with your supervisor. It’s a very important decision and can make your PhD defence much smoother.

During my PhD, I chose examiners that I had cited and based my work on their preliminary investigations.

But there are more things to think about before you write down their names!

Here’s a table checklist for choosing your PhD examiners.

| CHECKLIST | NOTES |

|---|---|

| Expert in relevant field | Your examiners should be well-acquainted with your research topic and be able to provide relevant and informed feedback. |

| Interdisciplinary knowledge | If your thesis spans multiple disciplines, it would be helpful to have examiners who understand all the fields involved. |

| Open-minded about cross-discipline work | Ensure your examiner is open-minded about works integrating different disciplines, as each field has unique ways of presenting findings. |

| Cited in your work | Consider examiners who you have cited in your work, as they are familiar with the type of work you’re doing. |

| Constructive Approach | Avoid examiners known for overly harsh or destructive feedback, you want someone who can critically analyze your work but also provide constructive comments. |

| Alignment with your methodology | The examiner should understand and ideally endorse the methodology you used. This ensures that they can productively critique your work’s design and execution. |

| Respect for critical viewpoints | If you’ve critiqued a particular scholar’s work in your thesis, ensure the scholar is professional enough to respect different viewpoints if considering them as an examiner. |

| Supervisor’s advice | Pay heed to your supervisor’s advice as they have experience in identifying suitable and appropriate examiners. |

First, compile a list of potential examiners who you believe would be appropriate for reviewing your thesis. Discuss your choices with your supervisor, explaining why you consider them suitable.

If your thesis spans multiple disciplines, consider choosing examiners from each discipline; it ensures intricate knowledge of each field is utilized.

However, ensure these examiners are open-minded about cross-discipline work, as disciplines tend to have unique ways of presenting their findings.

Listen to your supervisor’s advice.

They have experience in these matters and know who would be best qualified to examine your work.

Even if a scholar is high-profile or an editor of a favored journal, they might not be suitable due to methodological differences or varying research approaches.

Choosing the right examiner is crucial, as an ill-suited examiner could result in undesired outcomes. The goal is to establish a thoughtful academic conversation about your work.

How to Prepare for Dissertation Defense?

To prepare for your dissertation defense, start by understanding the specific requirements of your institute, as the process can vary across countries.

This could include:

- a presentation,

- a conversation with examiners,

- or a combination of both.

Once you know what to expect, practice vigorously. This should not be your first time discussing your work with others – engage in academic conversation, seek feedback and address challenging questions prior to the defense.

Breakdown your thesis into sections and time yourself on each section to manage length. Focus on the key points and avoid irrelevant details.

Creating a mock defense will be helpful in managing time and getting familiar with the process.

Prepare for potential questions. It’s not about cramming as much information as possible, but about understanding your work inside out. Start by preparing answers to common defense questions. In case of an unexpected question, don’t rush to answer. Take a moment, write down key points, and formulate an organized response.

Remember that the defense is an opportunity to showcase years of hard work.

Be confident, and don’t forget to breathe!

How Long Do Dissertation Defenses Usually Last?

The length of a dissertation defense can vary depending on factors such as the specific requirements of the institution and the complexity of the research being presented.

On average, a dissertation defense usually lasts between one to three hours.

During this time, the candidate will present their research and findings to a panel of experts, often including faculty members and fellow researchers.

The defense typically begins with an introduction by the candidate, followed by a detailed presentation of the research methodology, results, and conclusions.

Panel members then have the opportunity to ask questions and engage in a discussion with the candidate.

It is not unusual for defenses to be quite intense and challenging, as the panel seeks to assess the depth of the candidate’s knowledge and understanding of their research. In some cases, the candidate may be asked to leave the room while the panel deliberates before ultimately reaching a decision on the acceptance or rejection of the dissertation.

Wrapping up

As the culmination of the doctoral journey, the PhD defense demands meticulous preparation and understanding of its unique rigors.

This entails knowing the expectations of your dissertation committee, choosing the right examiners who offer constructive feedback, and putting considerable time into preparing for your oral defense.

The defense process isn’t a mere formality; it’s a critical examination of the candidate’s comprehension, originality, and critical thinking skills.

It provides an opportunity to exhibit your research and its contribution to your field, defend your arguments, and validate your years of labor.

Thus, selecting well-qualified examiners, anticipating potential questions, and honing your presentation skills are vital for a successful defense.

Students must be registered for their PhD program and finalize their dissertation prior to the defense, which can last anywhere from one to three hours, depending on the institution and the complexity of the research.

Any corrections or major revisions suggested by the dissertation committee members must be completed and submitted weeks prior to the conferral date.

A PhD defense isn’t just a rite of passage for doctoral candidates—it’s the final, decisive step on the journey to earning a doctorate.

It requires the full commitment of the candidate, their dissertation advisor, the committee chair, and all members involved, ensuring that the graduate studies department’s requirements are met, and that the student is admitted to the next phase of their academic or professional journey.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

- A Guide to Writing a PhD Literature Review

Written by Ben Taylor

Most PhD projects begin with a literature review, which usually serves as the first chapter of your dissertation. This provides an opportunity for you to show that you understand the body of academic work that has already been done in relation to your topic, including books, articles, data and research papers.

You should be prepared to offer your own critical analysis of this literature, as well as illustrating where your own research lies within the field – and how it contributes something new / significant to your subject.

This page will give you an overview of what you need to know about writing a literature review, with detail on structure, length and conclusions.

On this page

What is a phd literature review.

A literature review is usually one of the first things you’ll do after beginning your PhD . Once you’ve met with your supervisor and discussed the scope of your research project, you’ll conduct a survey of the scholarly work that’s already been done in your area.

Depending on the nature of your PhD, this work could comprise books, publications, articles, experimental data and more. This body of work is collectively known as the ‘scholarly literature’, on your subject. You won’t have to tackle any novels, poetry or drama during this review (unless, of course, you’re actually studying a PhD in English Literature, in which case that comes later).

The purpose of the PhD literature review isn’t just to summarise what other scholars have done before you. You should analyse and evaluate the current body of work , situating your own research within that context and demonstrating the significant original contribution your research will make.

Planning your PhD literature review

Your supervisor will be able to give you advice if you’re not quite sure where to begin your review, pointing you in the direction of key texts and research that you can then investigate. It’s worth paying attention to the bibliographies (and literature reviews!) of these publications, which can often lead you towards even more specialist texts that could prove invaluable in your research. At the same time, it’s important not to let yourself fall down an academic rabbit hole – make sure that the books and articles you’re surveying are genuinely relevant to your own project.

You should aim to include a broad range of literature in your review, showing the scope of your knowledge, from foundational texts to the most recent publications.

The note-taking process is crucial while you’re in the early stages of your literature review. Keep a clear record of the sources you’ve read, along with your critical analysis of their key arguments and what you think makes them relevant to your research project.

How long should a literature review be?

The length of a PhD literature review varies greatly by subject. In Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences the review will typically be around 5,000 words long, while STEM literature reviews will usually be closer to 10,000 words long. In any case, you should consult with your supervisor on the optimum length for your own literature review.

Structuring a PhD literature review

When you begin to write your PhD literature review, it’s important to have a clear idea of its outline. Roughly speaking, the literature review structure should:

- Introduce your topic and explain its significance

- Evaluate the existing literature with reference to your thesis

- Give a conclusion that considers the implications of your research for future study

The main body of your literature review will be spent critiquing the existing work that scholars have done in your field. There are a few different ways you may want to structure this part of the review, depending on the subject and the nature of your dissertation:

- Chronologically – If your research looks at how something has changed over time, it may make sense to review the literature chronologically, tracking the way that ideas, attitudes and theories have shifted. This might seem like quite a simple way to structure the review, but it’s also imperative to identify the common threads and sticking points between academics along the way, rather than merely reeling off a list of books and articles.

- Thematically – If your dissertation encompasses several different themes, you might want to group the literature by these subjects, while also emphasising the connections between them.

- Methodologically – If you are going to be working with experimental data or statistics, it could be a good idea to assess the different methods that previous scholars have used in your field to produce relevant literature.

Whichever technique you use to structure your literature review, you should take care not to simply list different books, articles and research papers without offering your own commentary.

Always highlight the similarities (and differences) between them, giving your analysis of the significance of these relationships, connections and contrasts.

Writing up a PhD literature review

The process of writing a literature review is different to that of writing the bulk of the dissertation itself. The aim at this point isn’t necessarily to illustrate your own original ideas and research – that’s what the dissertation is for – but rather to show the depth of your knowledge of the field and your ability to assess the work of other scholars . It’s also an opportunity for you to indicate exactly how your dissertation will make an original contribution to your subject area.

These are some tips to bear in mind when writing a literature review:

- Avoid paraphrasing – instead, offer your own evaluation of a source and its assertions

- Follow a logical path from one source or theme to the next – don’t make leaps between different books or articles without explaining the connection between them

- Critically analyse the literature – challenge assumptions, assess the validity of argument and write with authority

- Don’t be too broad in your scope – it can be easy to get carried away including every piece of related literature you come across, but it’s also important not to let your review become too sprawling or rambling

The fact that you usually begin your literature review right at the start of a PhD means that it’s likely you’ll come across plenty more relevant books and papers during the course of your research and while writing the dissertation. So, it’s useful to think of this first draft as a work-in-progress that you keep up-to-date as you write your thesis.

Finishing a PhD literature review

As you come to the end of your dissertation, it’s vital to take a close look at your initial literature review and make sure that it’s consistent with the conclusions that you’ve reached. Of course, a lot can change over the course of a PhD so it’s entirely possible that your research led you in a different direction than you imagined at the beginning.

The conclusion of your literature review should summarise the significance of the survey that you’ve just completed, explaining its relevance for the research your dissertation will undertake.

Literature reviews and PhD upgrade exams

The literature review is usually one of the first sections of a PhD to be completed, at least in its draft form. As such, it is often part of the material that you may submit for your PhD upgrade exam . This usually takes place at the end of your first year (though not all PhDs require it). Involves you discussing your work so far with academics in your department to confirm that your project is on track for a PhD. The feedback you get at this point may help shape your literature review, or reveal any areas you’ve missed.

Doing a PhD

For more information on what it’s like to do a PhD, read our guides to research proposals , dissertations and the viva . Or, search for your perfect PhD course on our website.

Our postgrad newsletter shares courses, funding news, stories and advice

You may also like....

What happens during a typical PhD, and when? We've summarised the main milestones of a doctoral research journey.

The PhD thesis is the most important part of a doctoral degree. This page will introduce you to what you need to know about the PhD dissertation.

This page will give you an idea of what to expect from your routine as a PhD student, explaining how your daily life will look at you progress through a doctoral degree.

PhD fees can vary based on subject, university and location. Use our guide to find out the PhD fees in the UK and other destinations, as well as doctoral living costs.

Our guide tells you everything about the application process for studying a PhD in the USA.

Postgraduate students in the UK are not eligible for the same funding as undergraduates or the free-hours entitlement for workers. So, what childcare support are postgraduate students eligible for?

FindAPhD. Copyright 2005-2024 All rights reserved.

Unknown ( change )

Have you got time to answer some quick questions about PhD study?

Select your nearest city

You haven’t completed your profile yet. To get the most out of FindAPhD, finish your profile and receive these benefits:

- Monthly chance to win one of ten £10 Amazon vouchers ; winners will be notified every month.*

- The latest PhD projects delivered straight to your inbox

- Access to our £6,000 scholarship competition

- Weekly newsletter with funding opportunities, research proposal tips and much more

- Early access to our physical and virtual postgraduate study fairs

Or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

*Offer only available for the duration of your active subscription, and subject to change. You MUST claim your prize within 72 hours, if not we will redraw.

Do you want hassle-free information and advice?

Create your FindAPhD account and sign up to our newsletter:

- Find out about funding opportunities and application tips

- Receive weekly advice, student stories and the latest PhD news

- Hear about our upcoming study fairs

- Save your favourite projects, track enquiries and get personalised subject updates

Create your account

Looking to list your PhD opportunities? Log in here .

How to structure your viva presentation (with examples)

Most PhD vivas and PhD defences start with a short presentation by the candidate. The structure of these presentations is very important! There are several factors and approaches to consider when developing your viva presentation structure.

Factors to consider when developing a viva presentation structure

Presenting a whole PhD in a short amount of time is very challenging. After all, a PhD is often the result of several years of work!

It is simply impossible to include everything in a viva presentation.

The structure of a viva presentation plays a crucial role in bringing across the key messages of your PhD.

Structuring your viva presentation traditionally

A very traditional viva presentation structure simply follows the structure of the PhD thesis.

The disadvantage of this traditional format is that it is very challenging to fit all the information in a – let’s say – 10-minute presentation.

Structuring your viva presentation around key findings

For instance, you can select your three main findings which you each connect to the existing literature, your unique research approach and your (new) empirical insights.

Furthermore, it might be tricky to find enough time during the presentation to discuss your theoretical framework and embed your discussion in the existing literature when addressing complex issues.

Structuring your viva presentation around key arguments

So, for example, your key argument 1 is your stance on an issue, combining your theoretical and empirical understanding of it. You use the existing theory to understand your empirical data, and your empirical data analysis to develop your theoretical understanding.

Structuring your viva presentation around case studies

Another common way to structure a viva presentation is around case studies or study contexts.

A viva presentation structure around case studies can be easy to follow for the audience, and shed light on the similarities and differences of cases.

Final thoughts on viva presentation structures

The key to a good viva presentation is to choose a structure which reflects the key points of your PhD thesis that you want to convey to the examiners.

The example viva presentation structures discussed here intend to showcase variety and possibilities and to provide inspiration.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox, 18 common audience questions at academic conferences (+ how to react), 10 reasons to do a master's degree right after graduation, related articles, how to organize and structure academic panel discussions, the best way to cold emailing professors, asking for a recommendation letter from a phd supervisor, energy management in academia.

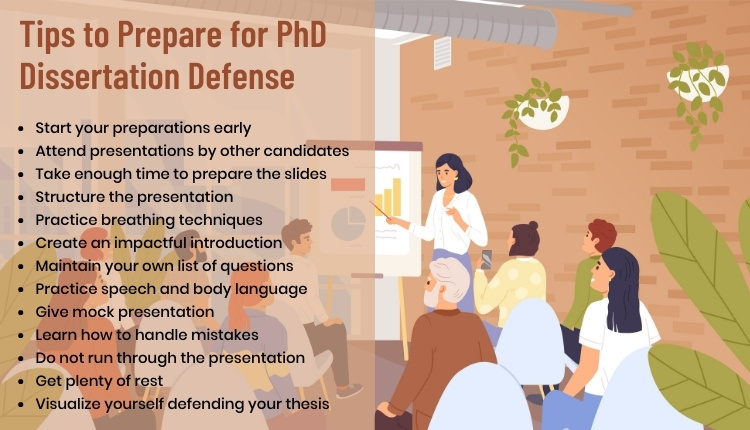

13 Tips to Prepare for Your PhD Dissertation Defense

How well do you know your project? Years of experiments, analysis of results, and tons of literature study, leads you to how well you know your research study. And, PhD dissertation defense is a finale to your PhD years. Often, researchers question how to excel at their thesis defense and spend countless hours on it. Days, weeks, months, and probably years of practice to complete your doctorate, needs to surpass the dissertation defense hurdle.

In this article, we will discuss details of how to excel at PhD dissertation defense and list down some interesting tips to prepare for your thesis defense.

Table of Contents

What Is Dissertation Defense?

Dissertation defense or Thesis defense is an opportunity to defend your research study amidst the academic professionals who will evaluate of your academic work. While a thesis defense can sometimes be like a cross-examination session, but in reality you need not fear the thesis defense process and be well prepared.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/c/JamesHaytonPhDacademy

What are the expectations of committee members.

Choosing the dissertation committee is one of the most important decision for a research student. However, putting your dissertation committee becomes easier once you understand the expectations of committee members.

The basic function of your dissertation committee is to guide you through the process of proposing, writing, and revising your dissertation. Moreover, the committee members serve as mentors, giving constructive feedback on your writing and research, also guiding your revision efforts.

The dissertation committee is usually formed once the academic coursework is completed. Furthermore, by the time you begin your dissertation research, you get acquainted to the faculty members who will serve on your dissertation committee. Ultimately, who serves on your dissertation committee depends upon you.

Some universities allow an outside expert (a former professor or academic mentor) to serve on your committee. It is advisable to choose a faculty member who knows you and your research work.

How to Choose a Dissertation Committee Member?

- Avoid popular and eminent faculty member

- Choose the one you know very well and can approach whenever you need them

- A faculty member whom you can learn from is apt.

- Members of the committee can be your future mentors, co-authors, and research collaborators. Choose them keeping your future in mind.

How to Prepare for Dissertation Defense?

1. Start Your Preparations Early

Thesis defense is not a 3 or 6 months’ exercise. Don’t wait until you have completed all your research objectives. Start your preparation well in advance, and make sure you know all the intricacies of your thesis and reasons to all the research experiments you conducted.

2. Attend Presentations by Other Candidates

Look out for open dissertation presentations at your university. In fact, you can attend open dissertation presentations at other universities too. Firstly, this will help you realize how thesis defense is not a scary process. Secondly, you will get the tricks and hacks on how other researchers are defending their thesis. Finally, you will understand why dissertation defense is necessary for the university, as well as the scientific community.

3. Take Enough Time to Prepare the Slides

Dissertation defense process harder than submitting your thesis well before the deadline. Ideally, you could start preparing the slides after finalizing your thesis. Spend more time in preparing the slides. Make sure you got the right data on the slides and rephrase your inferences, to create a logical flow to your presentation.

4. Structure the Presentation

Do not be haphazard in designing your presentation. Take time to create a good structured presentation. Furthermore, create high-quality slides which impresses the committee members. Make slides that hold your audience’s attention. Keep the presentation thorough and accurate, and use smart art to create better slides.

5. Practice Breathing Techniques

Watch a few TED talk videos and you will notice that speakers and orators are very fluent at their speech. In fact, you will not notice them taking a breath or falling short of breath. The only reason behind such effortless oratory skill is practice — practice in breathing technique.

Moreover, every speaker knows how to control their breath. Long and steady breaths are crucial. Pay attention to your breathing and slow it down. All you need I some practice prior to this moment.

6. Create an Impactful Introduction

The audience expects a lot from you. So your opening statement should enthrall the audience. Furthermore, your thesis should create an impact on the members; they should be thrilled by your thesis and the way you expose it.

The introduction answers most important questions, and most important of all “Is this presentation worth the time?” Therefore, it is important to make a good first impression , because the first few minutes sets the tone for your entire presentation.

7. Maintain Your Own List of Questions

While preparing for the presentation, make a note of all the questions that you ask yourself. Try to approach all the questions from a reader’s point of view. You could pretend like you do not know the topic and think of questions that could help you know the topic much better.

The list of questions will prepare you for the questions the members may pose while trying to understand your research. Attending other candidates’ open discussion will also help you assume the dissertation defense questions.

8. Practice Speech and Body Language

After successfully preparing your slides and practicing, you could start focusing on how you look while presenting your thesis. This exercise is not for your appearance but to know your body language and relax if need be.

Pay attention to your body language. Stand with your back straight, but relax your shoulders. The correct posture will give you the feel of self-confidence. So, observe yourself in the mirror and pay attention to movements you make.

9. Give Mock Presentation

Giving a trial defense in advance is a good practice. The most important factor for the mock defense is its similarity to your real defense, so that you get the experience that prepares for the actual defense.

10. Learn How to Handle Mistakes

Everyone makes mistakes. However, it is important to carry on. Do not let the mistakes affect your thesis defense. Take a deep breath and move on to the next point.

11. Do Not Run Through the Presentation

If you are nervous, you would want to end the presentation as soon as possible. However, this situation will give rise to anxiety and you will speak too fast, skipping the essential details. Eventually, creating a fiasco of your dissertation defense .

12. Get Plenty of Rest

Out of the dissertation defense preparation points, this one is extremely important. Obviously, sleeping a day before your big event is hard, but you have to focus and go to bed early, with the clear intentions of getting the rest you deserve.

13. Visualize Yourself Defending Your Thesis

This simple exercise creates an immense impact on your self-confidence. All you have to do is visualize yourself giving a successful presentation each evening before going to sleep. Everyday till the day of your thesis defense, see yourself standing in front of the audience and going from one point to another.

This exercise takes a lot of commitment and persistence, but the results in the end are worth it. Visualization makes you see yourself doing the scary thing of defending your thesis.

If you have taken all these points into consideration, you are ready for your big day. You have worked relentlessly for your PhD degree , and you will definitely give your best in this final step.

Have you completed your thesis defense? How did you prepare for it and how was your experience throughout your dissertation defense ? Do write to us or comment below.

The tips are very useful.I will recomend it to our students.