Encourage Better Peer Feedback with Our Guide to Feedback Rubrics

Giving and receiving peer feedback is a powerful learning tool. It enhances student engagement and performance , but only if done correctly. Feedback needs to be specific, organized, and actionable to work. Students need the skills to fully understand, analyze, and critique their peers’ work. The problem is that students aren’t teachers, so they don’t have years of experience leaving in-depth, qualitative feedback. A simple “good job” comment doesn’t lead to deeper learning for either the reviewer or the student who submitted the work. Feedback rubrics encourage better peer feedback by guiding students through the evaluation process. They act as the training wheels that keep students on track as they review their classmate’s work. As a result, both students benefit: the reviewer engages more deeply with the work, and the reviewee gets a more constructive critique of their work. We’re so passionate about peer reviews that we’ve put together a 60-page guide to building a feedback rubric. We’re sharing some of the highlights below, and you can download our ebook for an even more in-depth look at feedback rubrics.

What Is a Peer Feedback Rubric?

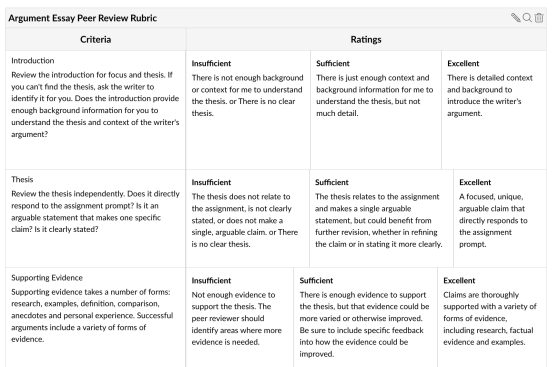

A peer feedback rubric is an assessment tool that students use to give their peers more comprehensive and constructive feedback on assignments. It consists of a series of open-ended questions that students answer as they review their peer’s work. Feedback rubrics overlap somewhat with grading rubrics, sometimes called matrix rubrics , but they are not the same. Matrix rubrics help you evaluate an assignment based on where an assignment falls on a continuum:

Matrix rubrics are useful for grading an assignment but they aren’t as useful for promoting individualized learning. Peer feedback rubrics might include scale questions, but they also employ open-ended questions that students must answer as they review their classmate’s assignment.

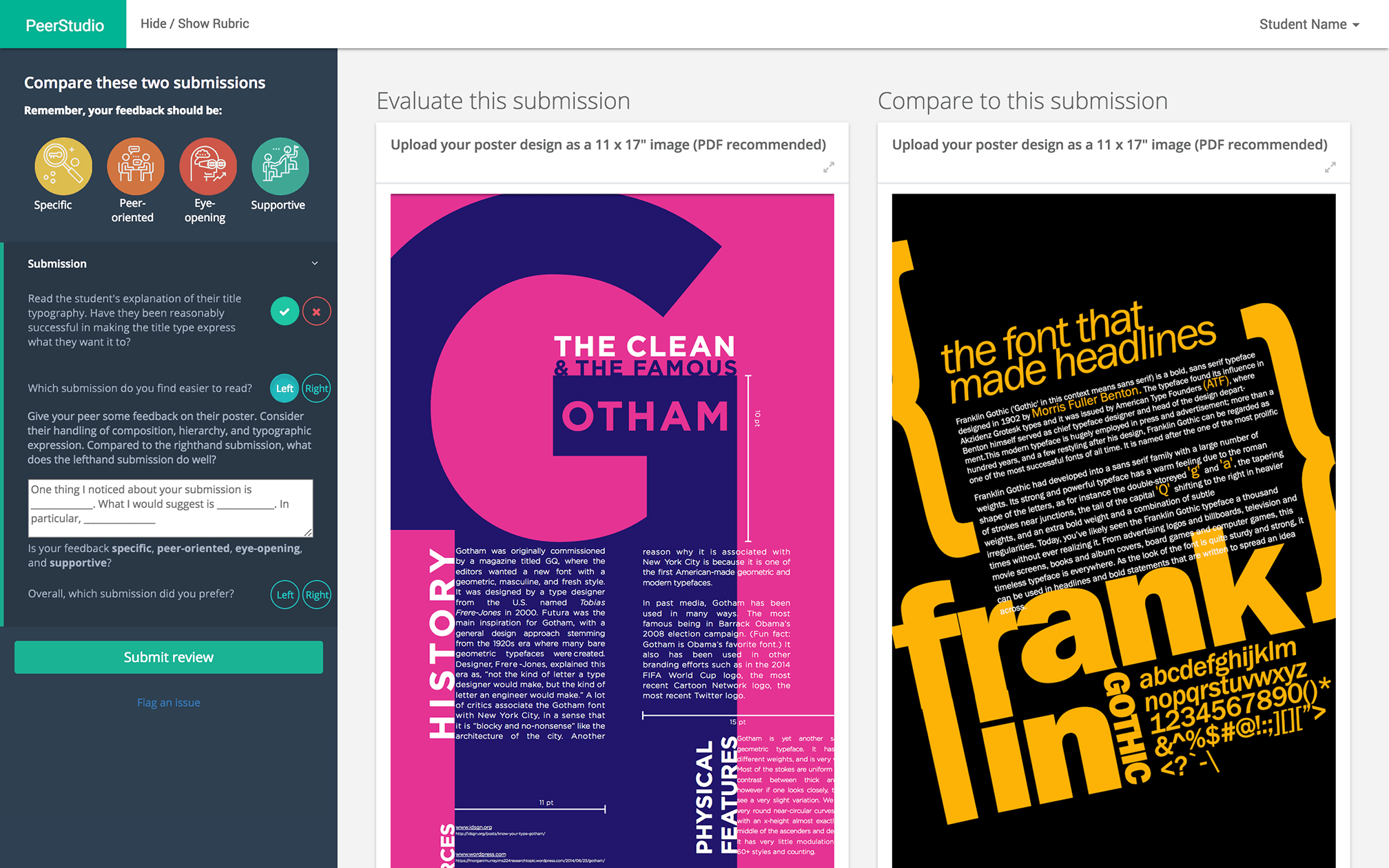

Writing their own answers requires original, critical thought, and promotes deeper learning. Because students learn both from receiving feedback and through the act of giving it. Here’s an example of a feedback rubric that incorporates different types of questions:

Rubrics are highly adaptable and can be used to facilitate feedback on almost any subject or assignment. Essay reviews are the most common, but your class could also use a rubric to peer review thesis statements before writing papers, to test code, or to review portfolios, videos or other artwork.

Best Practices for Using a Peer Feedback Rubric

Many students aren’t familiar with the concept of peer feedback rubrics or even a structured peer-review process. So before you send them off with a classmate’s work and a rubric in hand, give them some background. Explain the purpose of feedback tools and the skills this exercise will help them develop . Consider including the class in the actual creation of the rubric. The more input they have, the better they will understand what top-notch work should look like. Introduce the concept of constructive criticism. Many students need to learn how to give feedback that is helpful without being hurtful. Talk to them about the goals of peer feedback, and show them examples of kind, specific, and actionable comments. Show them examples of great assignments and effective rubrics. If you have time, go through a mock assignment in class, and assess it together. Provide anonymity. Anonymity is another key part of a good peer-review process. Anonymity eases anxiety and promotes honesty. Studies show that students write better feedback when they know their identity will remain hidden. Anonymity also eliminates any personal bias that might arise from preexisting student relationships.

Building Blocks of a Peer Feedback Rubric

Feedback rubrics consist of a series of questions that help students read, assess, and give feedback on their peers’ work. There is no one-size-fits-all formula for creating a rubric. Craft a series of questions that encourage students to assess the quality of the assignment and engage deeply with the content itself. These three types of questions are the building blocks of a feedback rubric:

Yes/No Questions

Yes/no questions are exactly what they sound like: a binary choice. The reviewer chooses between two options, with no other written follow-up. Yes/no questions are used to help gauge whether basic guidelines are being met. Stack a series of yes/no questions to create a checklist of elements students must fulfill to complete the assignment.

- Does the video have a beginning, a middle, and an end? Yes/No

- Did the writer correctly cite two independent research papers? Yes/No

Scale questions

Scale questions ask students to evaluate their classmate’s work by ranking it on a set scale. It’s similar to a matrix rubric, but there are no numerical values involved, just levels of mastery. Scale questions are useful for helping students understand expected learning outcomes from an assignment and for guiding them in their evaluation of the assignment’s quality. Example:

Text questions

Text questions are open-ended writing prompts that encourage reviewers to write long-form feedback about work they are reviewing. While yes/no and scale questions help reviewers assess the quality of the assignment, text questions are essential for assessing the reviewer’s mastery over the material. Ask questions that encourage deeper analysis and complex criticism. Encourage reviewers to get specific in their answers by asking for examples, narrowing in on a specific element of the assignment, or encouraging reflection. Examples:

- What was the thesis statement of this essay? Was it persuasive, and, if not, how could it be strengthened?

- How would you attempt to refute the argument presented in this essay?

Prompts Should Benefit Reviewer and Reviewee

An effective peer-review experience benefits both the reviewer and the reviewee. The reviewer enhances their grasp of the course materials through thinking critically about the assignment. At the same time, the reviewee receives in-depth constructive criticism of their work. To facilitate these dual benefits, your rubric should include questions that encourage the reviewer to both engage in higher-order thinking and leave good quality feedback for the reviewee.

Prompts for higher-order thinking

Thinking analytically about the assignment helps the reviewer deepen their knowledge and understanding of the material. These questions help them write a better review, but, more importantly, they help reviewers learn during the process. Ask questions that encourage the following: Critical thinking : Require students to justify their feedback with coherent arguments.

Example: Find a section of the text where the argument could be stronger. Explain why it’s not strong enough, and propose a stronger argument. Self-reflection : Ask students to explicitly state what they have learned from the review process.

Example: What is something new you learned about this topic from reading this submission? New perspectives : Highlight different perspectives to help students think about how their peers see the world.

Example: Imagine you are a film critic. What would be your review of this film?

Prompts for Effective Feedback

Effective feedback is kind, justified, specific, and constructive. Model this behavior both in class discussions around peer review and through the kind of questions you ask: Kind. Encourage reviewers to avoid stinging criticism in favor of feedback that is both encouraging and useful.

Example : Name the aspect of your peer’s assignment that you feel is the strongest. Justified. Have reviewers explain the thinking behind their judgments.

Example: Explain your evaluation using language from the rubric. Specific and Constructive. Vague, general feedback isn’t useful. Ask questions that require the reviewer to call out specific textual examples.

Example: Find a paragraph in this essay that works well. Explain why.

Learn More About Feedback Rubrics with Our Free Guide

The success of your classroom’s peer-review process hinges on your student’s ability to give quality feedback. A well-developed peer feedback rubric will help reviewers leave responses that are more insightful, and more detailed. Once the review is complete and students have had a chance to review their feedback, give the reviewee a chance to respond to that feedback. It makes students feel heard and helps the reviewer improve their work. You may even want to create a second rubric to help students give feedback on the feedback. For more information on building great feedback rubrics, check out our free Guide to Creating Effective Feedback Rubrics . It has more tips and sample rubrics by academic subject, as well as information on converting a matrix rubric into a feedback rubric.

Join our newsletter to receive the latest updates on pedagogy and online teaching.

Quick navigation

Talk to us the way you prefer, request a demo, get a quote, email sales.

Mastering Peer Evaluation with Effective Rubrics

Shreya verma.

Aug 1, 2023 • 5min read

Peer evaluation has emerged as a powerful process for fostering collaborative learning and providing valuable feedback to students. However, the process of peer evaluation can sometimes be ambiguous and subjective, leading to inconsistent outcomes. That's where rubrics come into play – these structured scoring guides bring clarity and objectivity to the peer evaluation process.

What are rubrics?

Rubrics are used to define the expectations of a particular assignment, providing clear guidelines for assessing different levels of effectiveness in meeting those expectations.

Instructors should consider using rubrics when conducting peer evaluation for the following reasons:

- Increase Transparency and Consistency in Grading: Rubrics promote transparency by outlining success criteria and ensuring consistent grading, fostering fairness in assessments.

- Increase the Efficiency of Grading: Rubrics streamline grading with predefined criteria, enabling quicker evaluations.

- Support Formative Assessment: Rubrics are useful for formative assessment, providing ongoing feedback for student improvement and progress over time.

- Enhance the Quality of Self- and Peer-Evaluation: Rubrics empower students as active learners, fostering deeper understanding and critical thinking through self-assessment and peer evaluation.

- Encourage Students to Think Critically: Rubrics link assignments to learning outcomes , stimulating critical thinking and encouraging students to reflect on their performance's alignment with intended outcomes.

- Reduce Student Concerns about Subjectivity or Arbitrariness in Grading: Rubrics offer a clear framework for evaluation, minimizing subjectivity and ensuring that assessments are based on specific criteria rather than subjective judgment.

Components of a Rubric

A rubric comprises several essential components that collectively define the evaluation criteria for a given module. Firstly, a clear task description is needed, outlining the expectations and requirements. This description serves as the foundation upon which students' work will be assessed. The scale helps in gauging performance levels by offering various ranges such as good-bad, always-never, or beginner-expert. Moreover, the rubric breaks down the evaluation into distinct dimensions , which are specific elements of expectations that together shape the overall assessment. These dimensions can encompass various aspects like timeliness, contribution, preparation, and more. Lastly, a rubric requires a definition of the dimensions , outlining the performance levels for each dimension and providing a clear understanding of the expectations at each level.

Types of Rubrics: Holistic vs Analytic

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Blog%20Post%20Images%20%20(19).png)

When it comes to assessing student performance, two common types of rubrics are employed: holistic and analytic .

Holistic rubrics use rating scales that encompass multiple criteria, emphasizing what the learner can demonstrate or accomplish. These rubrics are easier to develop and use, providing consistent and reliable evaluations. However, they do not offer specific feedback for improvement and can be challenging to score accurately.

In contrast, analytic rubrics use rating scales to evaluate separate criteria, usually presented in a grid format. Each criterion is associated with descriptive tags or numbers that define the required level of performance. Analytic rubrics provide detailed feedback on areas of strength and weakness, and each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance. While they offer more comprehensive feedback, creating analytic rubrics can be more time-consuming, and maintaining consistency in scoring may pose a challenge.

Holistic rubrics are preferable when grading work or measuring overall progress and general performance. On the other hand, analytic rubrics are more suitable for evaluating multiple areas or criteria separately, allowing for a more detailed assessment of proficiency in each area.

Rubrics in Formative vs Summative Assessments

When deciding between using a holistic or analytic rubric, several factors come into play. One crucial consideration is the purpose of the rubric and how it aligns with the assessment goals.

For formative assessment , where the focus is on providing ongoing feedback and supporting student learning, a holistic rubric might be more suitable. It allows educators to assess progress comprehensively, giving students an overall understanding of their performance.

In contrast, for summative assessment , where the emphasis lies on making final evaluations, an analytic rubric could be more effective. It breaks down the evaluation into distinct criteria, offering specific feedback on each area of assessment, enabling a more detailed and precise evaluation.

Examples of Rubrics in Peer Evaluation for Team-based Learning

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Blog%20Post%20Images%20%20(20).png)

Analytic rubrics, like Koles' and Texas Tech's methods , evaluate individual criteria separately, providing detailed feedback on various aspects of performance. Additionally, UT Austin's method, which is useful for formative assessments, focuses on ongoing feedback to support student learning and growth throughout the evaluation process. In contrast, holistic rubrics, such as Michaelsen's and Finks' methods , create an overall assessment score, capturing a comprehensive view of a student's performance. For an overview of these methods, fill out the form here to gain access to our Peer Evaluation Methods guide.

All in all, rubrics empower both educators and students to engage in meaningful and effective evaluations. The thoughtful application of rubrics ensures fair and transparent evaluations, ultimately contributing to enhanced learning outcomes.

Free Download

Peer evaluation methods guide, join our newsletter community, recommended for you, the 5 benefits of peer evaluation in team-based learning.

Peer evaluation is an integral part of

5 Reasons Why Immediate Feedback is Important for Effective Learning

Educators are always searching for teaching

PBL vs TBL: What's the Difference?

Educators are always looking for effective

3 Benefits of e-Gallery Walk for Students

InteDashboard can be used to conduct an online

Pros and Cons of The 4 Peer Evaluation Methods for Team-Based Learning

If you have been following our blog, you

What is Team-based Learning?

Team-based learning began as a way to improve

7 Benefits of Switching from IF-AT Scratch-off Cards to Digital TRAT

In 2015, after I had left as CFO of an airline

4 Benefits of Team-based Learning for Students

Hate sitting through hours of boring lectures

Testimonials

- Department & Units

- Majors & Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Knowledge base

- Administrative Applications

- Classroom Support & Training

- Computer & Desktop Support

- Equipment Loans & Reservations

- Lecture Recording

- Media Center

- Research Support & Tools

- Emergency Remote Teaching

- Website Services & Support

- Support Hours

- Walk-in Support

- Access Controls

- Student Resources

- Support LSA

- Course Guide

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

| {{item.snippet}} |

Dynamic Rubrics: The Key to Better Peer Review

- News & Events

- Teaching Tip of the Week

- Search News

Innovate Newsletter

Peer review refers to the process of students reviewing and providing constructive feedback on each other's writing. Integrating peer review into writing assignments—whether they be essays or other projects with writing components—encourages students to develop a number of beneficial skills. Not only is peer review an active learning tool that empowers students to better understand their own writing process, but when successful, it can help boost student confidence in their writing and improve their communication skills. Peer review can also help students better familiarize themselves with the requirements of the assignment (Crossman and Kite, 2012), reducing their reliance on instructor feedback while improving results.

But ask a class about their opinions on peer review, and you’re certain to hear a range of complaints. While many students see value in peer review, just as many have encountered challenges. Students may feel uncertain about their ability to provide valuable feedback, especially if they are still developing their own writing skills. They may worry about giving incorrect advice or fear hurting their peers' feelings or damaging relationships. They may hesitate to offer honest and constructive criticism, leading to vague or overly positive feedback that may not contribute to meaningful improvement. Most importantly, if they have not received proper guidance or instruction on how to provide constructive feedback, students may struggle to offer specific and helpful suggestions.

Ideally, such guidance involves multiple steps. First, develop a dynamic rubric that closely aligns with assignment goals and your own assessment criteria. What is a dynamic rubric? One that is flexible, changes to meet assessment needs, and engages students.

Is this likely your students’ first college-level writing assignment? Are they advanced students who have varied prior writing experience? The level of guidance and support your students need will depend heavily on how much experience they have not just with writing but with the subject matter as well. More senior students writing within their major may need less guidance than students in an undergraduate survey course, but even more advanced students can benefit from a peer review rubric.

How to Build Dynamic Peer Review Rubrics

Align rubric criteria with assessment criteria.

If you already have a grading rubric for the assignment, use that as a guide for the peer review rubric. Without guidance, many students will only focus on grammar and mechanics when reviewing their peers’ work (Feltham and Sharon, 2015), which may not even be included in your final grading criteria. Including criteria specific to the assignment’s goals will not only make your own grading criteria more transparent, but it will also encourage students to broaden their definitions of revision to include both content and form.

Provide Models of Levels of Performance

If you’re using levels of performance in your rubric (i.e. insufficient, sufficient, excellent, etc.), provide models of what those levels look like for the specific assignment. Students often have difficulty gauging the nuances of content and development, so including those models and discussing them with the class can lead to more accurate peer critiques.

Consider student background and experience as well. A “sufficient” score in a survey course will probably look different from a “sufficient” score in a more advanced course for upper-level majors. It may even vary by assignment–this is where the dynamic aspect of rubric-building comes in.

You may consider providing space for open-ended questions where students can share their observations without the limitations of a scale, like “Were there any areas of the essay where you were confused, or needed more information to better understand the writer’s point?”

Use Canvas Rubrics to Streamline the Process

If conducting peer review in Canvas, consider creating your peer review rubric in Canvas as well. This can streamline the process for students, as they will be prompted to use the rubric associated with the peer submission. This also streamlines your ability to organize and review student feedback.

Once you have a rubric, have students practice using the rubric with their own drafts. Finally, directly address known student concerns, like uncertainty about their own writing skills and fears of hurting feelings. Often, having a frank discussion helps students feel more comfortable with providing constructive feedback.

Peer Review Rubric Examples and Resources

- Examples and Supplemental Material from the Sweetland Center for Writing

- U of M Center for Academic Innovation’s Rubric Examples

- Canvas Guide: How to Create a Peer Review Assignment

- Research Paper Peer Review Rubric from the University of Hawaii

Interested in using Canvas rubrics for peer review, or have questions about building a dynamic rubric? Request a consultation with an LSA Instructional Consultant for help.

References:

Crossman, J. A., Kite, S. L. (2012). Facilitating improved writing among students through directed peer review. Active Learning in Higher Education, 13(3), 219–229. DOI: 10.1177/1469787412452980

Feltham, M., Sharen, C. “What do you mean I Wrote a C Paper?” Writing, Revision, and Self-Regulation. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching. Vol. VIII. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1069881.pdf

| Release Date: | 03/21/2024 |

|---|---|

| Category: | ; |

| Tags: |

Office of the CIO

News & events, help & support, getting started with technology services.

TECHNOLOGY SERVICES

G155 Angell Hall, 435 South State St, Ann Arbor, MI 48109–1003 734.615.0100 [email protected]

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Academic Advising

- Majors and Minors

- Departments and Units

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context

On this page:, the what and why of peer review, considerations for successful peer review design and implementation.

- Instructional Technologies to Support Peer Review

- Columbia University Resources

- References and Additional Resources

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/peer-review/

Peer review, as the name suggests, is the act of receiving feedback from a colleague or classmate. It typically happens throughout the course of a written assignment, perhaps at the halfway point, and often involves classmates commenting and providing feedback on each other’s work in any number of formats. There might be specific questions or prompts provided by the instructor, or the activity may be based on the writer’s specific concerns.

The process of peer review can help students make purposeful and intentional choices in their own work by offering their perspective and insight to their peers. It also gives students an opportunity to see how others have responded to a similar prompt, text, or assignment, which can help their own understanding of the topic or assignment grow. In their research on the benefits of peer review, Ambrose et al. (2010) demonstrate how the peer review process has mutual benefits for “readers, writers, and instructors alike” (pp. 257). For readers, peer review can help them re-see their own work. For writers, the feedback gained in peer review can help focus the revision process. Finally, instructors also benefit because they receive work that has already undergone at least one round of feedback and revision. Research has shown that students who receive focused feedback from at least four peers have better revision than those who received instructor feedback only (Ambrose et. al, 2010, pp. 257). Thus, it is important to have clear processes and expectations for peer review, as well as multiple opportunities available throughout a course.

When planning peer review activities, it is important for instructors to consider the overall assignment learning objectives, scaffolded in-class activities, peer review expectations, and the goals of peer review for students. With the various components of the assignment in mind, designing peer review activities will be more intentional and can further support students’ success on a given assignment.

| 1. | Align the peer review activity with the learning objectives for the writing assignment. | ||

| 2. | Design peer review activity with all elements of writing in mind. (e.g.: necessary prep work, timing of the activity, time for feedback implementation) | ||

| 3. | Model expectations. (e.g.: demo of peer review with students) | ||

| 4. | Identify a clear assessment plan for peer review activities and share that with students. | ||

| 5. | Determine platform(s) or tool(s) needed for your context. | ||

| In-person | Hybrid (HyFlex) | Online | |

| – Small groups in class – Collaborative doc – CourseWorks | – Breakout rooms – Collaborative doc – CourseWorks | – Breakout rooms – Collaborative doc – CourseWorks | |

1. Align the peer review activity with the learning objectives for the writing assignment.

What are the goals for the peer review activity, and what parts of the assignment do they align with? What questions or concepts will students address in the activity?

Aligning peer review activities with the learning objectives of the assignment can help students strengthen their connections and understanding of assignment expectations. This alignment can also help target feedback so that students are focusing on the parts of the assignment they need to be successful. Early opportunities and activities that ask students to provide targeted feedback (e.g.: concrete suggestions and examples) allows them to practice the skills identified in the assignment learning objectives and may help them identify similar writing needs in their own work. Lastly, providing students with a guided peer review activity can help offset surface-level comments (e.g.: “This looks good!”) or an over-focus on line-by-line copyediting.

2. Design the peer review activity by considering all elements of the writing assignment.

When will students receive peer feedback versus instructor feedback? What in-class activities will students have completed prior to peer review?

Think about the moments of intervention throughout the assignment and how each of these moments might build upon the next. This can help you scaffold students’ feedback throughout the assignment, as well further align class activities and learning objectives. It’s also important to consider what students will need to prepare for the peer review activity: what will you ask them to share during the activity? How much of their draft should they bring for peer review? Lastly, be clear with students about your expectations for timing: What amount of synchronous or in-class time will students have for the activity? What will the out-of-class expectations be? When deciding how much time you allot, be mindful of students’ different learning preferences and language experiences.

3. Model your expectations for successful peer review.

What does successful peer review look like in your class? How will students know what the expectations are?

As John Bean (2011) notes, “Unless the teacher structures the sessions and trains students in what to do, peer reviewers may offer eccentric, superficial, or otherwise unhelpful–or even bad–advice” (pp. 295). One way you might train students is to engage them in whole-class peer review using a sample paper. There is no way to know what students’ previous peer review experiences have been, so offering a whole class model can help establish expectations early on. You can also partner with your students to create clear peer review guidelines , helping students learn how to evaluate each other’s work. Additionally, you might choose to share your own experiences with peer review with your students. Reflect upon what kinds of feedback you found most and least helpful, and share that with students, and even invite them to join that reflection and discussion. This can serve as a springboard for a conversation about your class peer review expectations.

4. Identify a clear assessment plan for peer review activities, and share that with students.

Will you assess students’ participation and contributions? If so, what will that look like? If you assess peer review, how will you help students develop those skills? (See item 3 above.)

If you decide to assess students’ peer review participation, be sure to have clear conversations about these expectations with students. You might refer to established peer review guidelines (discussed above). If you have a rubric for the assignment, you might also consider if peer review is a part of that rubric. Or, you might encourage students to use the assignment rubric as a peer review activity and assess students’ engagement with the rubric. Lastly, peer review activities present a great opportunity for a low-stakes assessment in the classroom, which are known to reduce student anxiety and increase students’ confidence in their work ( Lang, 2013 ).

5. Determine the platform or tool that will help facilitate peer review.

What platform(s) or tool(s) will best help facilitate the peer review activity? What level of instruction or preparation will students need prior to engaging in the activity?

While sharing hard-copies of drafts is a common practice for in-person class meetings, there are a number of different ways students can engage in online peer review. After determining the appropriate activity based on the learning objectives and students’ needs, choosing the right tool or platform can ensure that students are able to achieve the goals of the activity. Read on to learn about platform or tool considerations.

Back to Top

Instructional Technologies to Support Peer Review

Zoom Breakout Rooms, Google Docs, and CourseWorks (Canvas) can be used to help facilitate peer review. Find the platform or tool that will work best for your course context. Need assistance? Contact the CTL at [email protected] .

Zoom Breakout Rooms

Zoom breakout rooms can be used during synchronous class sessions to simulate the small group discussions that may take place during in-class peer review. You can pre-assign students in peer review pairs or groups, or you can assign students randomly in the moment. With pre-assignments, you will want to consider if students will remain in the same peer review groups throughout the semester or if you’ll switch groups up across assignments. Additionally, will students be asked to read each other’s work ahead of the breakout room activity? If so, be sure to provide explicit expectations about what students should address and do in preparation for and during the peer review activity.

See Zoom Help Center “ Enabling breakout rooms ;” “ Manage breakout rooms ;” and “ Pre-assign participants to breakout rooms .”

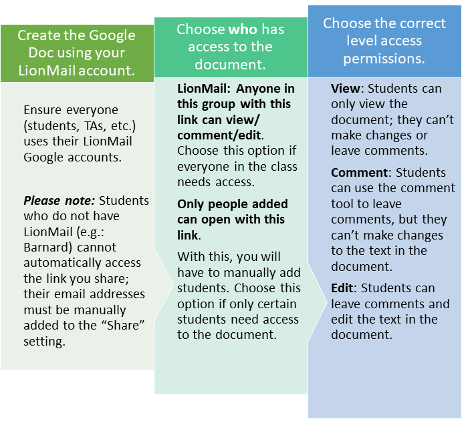

Google Docs

Google Docs are a great tool for synchronous and asynchronous peer review. They are also particularly useful if you are planning to assess students’ peer review participation. Google Docs can be a valuable peer review facilitation tool, regardless of classroom format; whether in-person or online, synchronous or asynchronous, they can be used to help students foster their feedback skills.

For synchronous class sessions or face-to-face classes , you might pair the Google Doc with small group peer review, either in-class or via Zoom breakout rooms. Students could be working in the same collaborative writing space while also talking with each other about their work and comments they are making. As the instructor, you can see students’ comments and feedback in real time, even if you do not join the breakout room discussions.

Asynchronously, or for work done outside of a face-to-face course , you might ask students to share their work with each other and leave comments and feedback throughout the document. Students can respond to questions and comments left on the document, and the reviewers will be notified, prompting a dialogue. Additionally, there is a chat function within Google Docs , so two or more students, if working in the document at the same time, could ask questions and talk via chat. You may even consider pairing an asynchronous peer review activity with a brief in-class activity between pairs/groups.

Creating and Sharing a Google Doc: Settings and Permissions Considerations: When using Google Docs, there are some important considerations related to sharing settings and access. The image below includes some of these steps and considerations; for more about sharing within LionMail, see CUIT’s LionMail (Google) Drive help page .

Accessible Graphic (PDF)

CourseWorks (Canvas)

You can use CourseWorks to facilitate peer review activities through a number of tools. Two of the most common ones include the Peer Review Function and the Discussions Tool .

Peer Review Function: As its name suggests, the peer review function in CourseWorks allows the instructor to assign student work to others for review. This function is particularly useful in large classes (50+) as it helps manage the logistics of assigning peer review groups. It is also useful if you want to assign specific papers or work to specific students, or if you want the option for anonymous peer review comments. Any assignment you create in CourseWorks can be assigned to peer review; once selected, you can manually assign students work to peer review, or CourseWorks can randomly allocate the papers.

For more detailed information on assigning Peer Review in CourseWorks visit the Canvas help documentation .

Discussions Tool: The Discussions tool allows students to easily share their work with each other. They can post their work as an attachment to a discussion post, (e.g. Word document, PDF) or by sharing a Google Doc link in the post itself. Because of its availability to the entire class, the Discussions tool is particularly useful when you want the whole class to see peers’ work, or if the number of viewers does not matter. If you would like to limit the view to only a number of select students, you can also assign a Discussion to a group of students and only those in that particular group will see the posts.

No matter the use of the Discussions tool, whether through the whole-class or for select groups, it’s important to provide clear instructions that articulate the peer review goals and activity, as well as your expectations, for students. For instructions on how to create Discussion posts, visit the Canvas help documentation.

Columbia Resources

CTL Knowledge Base CTL Office Hours and Support

Writing Centers provide various services to support students and their writing. They are a great resource for students’ to get additional feedback and support throughout the writing process, whether at the initial brainstorming stage or as students work to implement peer or instructor feedback.

Barnard Writing Center Columbia Writing Center Columbia School of Social Work Writing Center Teachers College Graduate Writing Center

References

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Norman, M.K. (2010). What is reader response/peer review and how can we use it? In S.A. Ambrose et al. How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching (pp. 257-9). Jossey-Bass.

Bean, J. C. (2011). Have students conduct peer reviews of drafts. Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom, 2nd Edition (pp. 295-302). Jossey-Bass.

Lang, J.M. (2013). Cheating lessons: Learning from academic dishonesty . Harvard University Press.

Science Education Resource Center (SERC) at Carleton College. (n.d.). Guidelines for students – peer review . Pedagogy in Action: the SERC Portal for Educators.

Additional Resources

Salahub, J. (1994-2020). Peer review . The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University.

University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT). (n.d.). Feedback on student writing . CRLT.

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Peer Review Rubric

- Available Topics

- Top Documents

- Recently Updated

- Internal KB

Peer Feedback Rubric

(Source: UW-Madison BioCore ) Another way you will work in groups or pairs is through peer review, an opportunity for you to give and receive peer feedback on your papers before you turn them in to be graded by your TA. Writing is a form of communication; a peer can tell you whether or not your paper makes sense. It is to your advantage to take your responsibility to review a peer’s paper seriously . We find that the review process benefits the reviewer and the author because it gives you practice evaluating a paper by applying the same criteria your TA will use to evaluate your paper.

Note that you do not need to wait for us to assign a formal review to take advantage of the peer-review process. You can always get together with other students and act as reviewers for each other’s papers, even when it is not required as part of an assignment!

Peer review is a skill that takes practice. Use the following criteria when you are learning how to peer review. To help you become a more skilled peer reviewer, we will ask you to hand in your peer review comments to be evaluated by your TA. Your TA will use these same criteria to evaluate your peer review.

| Criteria | 1 - Adequate | 2 - Good | 3 - Excellent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus on “Global Concerns” (larger structural, logic/reasoning issues) rather than detailed “Local Concerns” (spelling, grammar, formatting) | Does not identify missing components. Comments are restricted to spelling, grammar, formatting, and general editing. | Identifies most components as present or absent. One or two global concerns comments on a paper requiring more focus. Significant comments are focused at the local concerns/ editing level. | Can identify all components of paper as present or absent. Provides logical and well-reasoned critique. Recognizes logical leaps and missed opportunities to make connections between parts of the paper. Provides a good balance of comments addressing ‘global concerns’ and minor comments addressing ‘local concerns.’ |

| Thorough, constructive critique, including a balance* of positive and negative comments | The review is entirely positive or negative, with little support or reasoning provided. | Those are good comments, but they are not balanced as positive and negative or not supported by reasoning. | Supports the author’s efforts with sincere, encouraging remarks, giving them a foundation to build for subsequent papers. Critical comments are tactfully written. |

| Evidence of thorough reading and review of the paper | Comments focused on one or two distinct issues but not on the overall reasoning and connectedness of all sections in the paper. The reviewer did not read the entire paper or skimmed through too quickly to understand. | Evidence that the reviewer read the entire paper but did not provide a thorough review. | Comments on all parts of the paper and connections between paper sections. Comments are clear and specific and offer suggestions for revision rather than simply labeling a problem. Appropriate comment density demonstrates the reviewer’s investment in peer review while not overwhelming the writer. |

| Outlines both general and specific areas that need improvement and provides suggestions | The review is too general to guide author revision or too specific to help the author on subsequent papers. | Provides both general and specific comments but no suggestions on how to improve. | Supplies author with productive comments, both general and specific, for areas of improvement. General comments are those that authors may use in subsequent papers, whereas specific comments pertain to the specific paper topic and assignment. Comments come with suggestions for improvement. |

| Keywords | rubric, peer review, feedback, student | Doc ID | 114199 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Timmo D. | Group | Instructional Resources |

| Created | 2021-10-08 13:00:25 | Updated | 2024-04-23 13:35:10 |

| Sites | Center for Teaching, Learning & Mentoring | ||

| Feedback | 10 0 | ||

University Writing Program

- Collaborative Writing

- Writing for Metacognition

- Supporting Multilingual Writers

- Alternatives to Grading

- Making Feedback Matter

- Peer Review

- Responding to Multilingual Writers’ Texts

- Model Library

Written by Arthur Russell

Just about every discussion of rubrics begins with a caveat: writing rubrics are not a substitute for writing instruction. Rubrics are tools for communicating grading criteria and assessing student progress. Rubrics take a variety of forms, from grids to checklists , and measure a range of writing tasks, from conceptual design to sentence-level considerations.

As with any assessment tool, a rubric’s effectiveness is entirely dependent upon its design and its deployment in the classroom. Whatever form rubrics take, the criteria for assessment must be legible to all students—if students cannot decipher our rubrics, they are not useful.

When effectively integrated with writing instruction, rubrics can help instructors clarify their own expectations for written work, isolate specific elements as targets of instruction, and provide meaningful feedback and coaching to students. Well-designed rubrics will draw program learning outcomes, assignment prompts, course instruction and assessment into alignment.

Starting Points

Course rubrics vs. assignment rubrics.

Instructors may choose to use a standard rubric for evaluating all written work completed in a course. Course rubrics provide instructors and students a shared language for communicating the values and expectations of written work over the course of an entire semester. Best practices suggest that establishing grading criteria with students well in advance helps instructors compose focused, revision-oriented feedback on drafts and final papers and better coach student writers. When deploying course rubrics in writing-intensive courses, consider using them to guide peer review and self-evaluation processes with students. The more often students work with established criteria, the more likely they are to respond to and incorporate feedback in future projects.

At the same time, not every assignment needs to assess every aspect of the writing process every time. Particularly early in the semester, instructors may develop assignment-specific rubrics that target one or two standards. Prioritizing a specific learning objective or writing process in an assignment rubric allows instructors to concentrate time spent on in-class writing instruction and encourages students to develop targeted aspects of their writing processes.

Developing Evaluation Criteria

- Establish clear categories. What specific learning objectives (i.e. critical and creative thinking, inquiry and analysis) and writing processes (i.e. summary, synthesis, source analysis, argument and response) are most critical to success for each assignment?

- Establish observable and measurable criteria of success. For example, consider what counts for “clarity” in written work. For a research paper, clarity might attend to purpose: a successful paper will have a well-defined purpose (thesis, takeaway), integrate and explain evidence to support all claims, and pay careful attention to purpose, context, and audience.

- Adopt student-friendly language. When using academic terminology and discipline-specific concepts, be sure to define and discuss these concepts with students. When in doubt , VALUE rubrics are excellent models of clearly defined learning objective and distinguishing criteria.

Sticking Points: Writing Rubrics in the Disciplines

Even the most carefully planned rubrics are not self-evident. The language we have adopted for writing assessment is itself a potential obstacle to student learning and success . What we count for “clarity” or “accuracy” or “insight” in academic writing, for instance, is likely shaped by our disciplinary expectations and measured by the standards of our respective fields. What counts for “good writing” is more subjective than our rubrics may suggest. Similarly, students arrive in our courses with their own understanding and experiences of academic writing that may or may not be reflected in our assignment prompts.

Defining the terms for success with students in class and in conference will go a long way toward bridging these gaps. We might even use rubrics as conversation starters, not only as an occasion to communicate our expectations for written work, but also as an opportunity to demystify the rhetorical contexts of discipline-specific writing with students.

Helpful Resources

For a short introduction to rubric design, the Creating Rubrics guide developed by Louise Pasternack (2014) for the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation is an excellent resource. The step-by-step tutorials developed by North Carolina State University and DePaul Teaching Commons are especially useful for instructors preparing rubrics from scratch. On the use of rubrics for writing instruction and assignments in particular, Heidi Andrade’s “Teaching with Rubrics: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly” provides an instructive overview of the benefits and drawbacks of using rubrics. For a more in-depth introduction (with sample rubrics), Melzer and Bean’s “Using Rubrics to Develop and Apply Grading Criteria” in Engaging Ideas is essential reading.

Cited and Recommended Sources

- Andrade, Heidi Goodrich. “Teaching with Rubrics: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” College Teaching , vol. 53, no. 1, 2005, pp. 27–30, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27559213

- Athon, Amanda. “Designing Rubrics to Foster Students’ Diverse Language Backgrounds.” Journal of Basic Writing , vol. 38, No.1, 2019, pp. 78–103, https://doi.org/10.37514/JBW-J.2019.38.1.05

- Bennett, Cary. “Assessment Rubrics: Thinking inside the Boxes.” Learning and Teaching: The International Journal of Higher Education in the Social Sciences , vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, pp. 50–72, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718020

- Broad, Bob. What We Really Value: Beyond Rubrics in Teaching and Assessing Writing . University Press of Colorado, 2003. https://doi-org.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/10.2307/j.ctt46nxvm

- Melzer, Dan, and John C. Bean. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . 3rd ed., Jossey-Bass, 2021 (esp. pp. 253-277), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/lib/jhu/detail.action?docID=6632622

- Pasternack, Louise. “Creating Rubrics,” The Innovative Instructor Blog , Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation, Johns Hopkins University, 21 Nov. 2014.

- Reynders, G., et al. “Rubrics to assess critical thinking and information processing in undergraduate STEM courses.” International Journal of STEM Education vol. 7, no. 9, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00208-5

- Turley, Eric D., and Chris W. Gallagher. “On the ‘Uses’ of Rubrics: Reframing the Great Rubric Debate.” The English Journal , vol. 97, no. 4, 2008, pp. 87–92, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30047253

- Wiggins, Grant. “The Constant Danger of Sacrificing Validity to Reliability: Making Writing Assessment Serve Writers.” Assessing Writing , vol. 1, no. 1, 1994, pp. 129-139, https://doi.org/10.1016/1075-2935(94)90008-6

Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library, teaching students to evaluate each other, why use peer review.

Peer assessment, or review, can improve overall learning by helping students become better readers, writers, and collaborators. A well-designed peer review program also develops students’ evaluation and assessment skills. The following are a few techniques that instructors have used to implement peer review.

Planning for peer review

- Identify where you can incorporate peer review exercises into your course.

- For peer review on written assignments, design guidelines that specify clearly defined tasks for the reviewer. Consider what feedback students can competently provide.

- Determine whether peer review activities will be conducted as in-class or out-of-class assignments (or as a combination of both).

- Plan for in-class peer reviews to last at least one class session. More time will be needed for longer papers and papers written in foreign languages.

- Model appropriate constructive criticism and descriptive feedback through the comments you provide on papers and in class.

- Explain the reasons for peer review, the benefits it provides, and how it supports course learning outcomes.

- Set clear expectations: determine whether students will receive grades on their contributions to peer review sessions. If grades are given, be clear about what you are assessing, what criteria will be used for grading, and how the peer review score will be incorporated into their overall course grade.

Before the first peer review session

- Give students a sample paper to review and comment on in class using the peer review guidelines. Ask students to share feedback and help them rephrase their comments to make them more specific and constructive, as needed.

- Consider using the sample paper exercise to teach students how to think about, respond to, and use comments by peer reviewers to improve their writing.

- Ask for input from students on the peer review worksheet or co-create a rubric in class.

- Prevent overly harsh peer criticism by instructing students to provide feedback as if they were speaking to the writer or presenter directly.

- Consider how you will assign students to groups. Do you want them to work together for the entire semester, or change for different assignments? Do you want peer reviewers to remain anonymous? How many reviews will each assignment receive?

During and after peer review sessions

- Give clear directions and time limits for in-class peer review sessions and set defined deadlines for out-of-class peer review assignments.

- Listen to group discussions and provide guidance and input when necessary.

- Consider requiring students to write a plan for revision indicating the changes they intend to make on the paper and explaining why they have chosen to acknowledge or disregard specific comments and suggestions. For exams and presentations, have students write about how they would approach the task next time based on the peer comments.

- Ask students to submit the peer feedback they received with their final papers. Make clear whether or not you will be taking this feedback into account when grading the paper, or when assigning a participation grade to the student reviewer.

- Consider having students assess the quality of the feedback they received.

- Discuss the process in class, addressing problems that were encountered and what was learned.

Examples of peer review activities

- After collection, redistribute papers randomly along with a grading rubric. After students have evaluated the papers ask them to exchange with a neighbor, evaluate the new paper, and then compare notes.

- After completing an exam, have students compare and discuss answers with a partner. You may offer them the opportunity to submit a new answer, dividing points between the two.

- In a small class, ask students to bring one copy of their paper with their name on it and one or two copies without a name. Collect the “name” copy and redistribute the others for peer review. Provide feedback on all student papers. Collect the peer reviews and return papers to their authors.

- For group presentations, require the class to evaluate the group’s performance using a predetermined marking scheme.

- When working on group projects, have students evaluate each group member’s contribution to the project on a scale of 1-10. Require students to provide rationale for how and why they awarded points.

Peer review technologies

Best used for providing feedback (formative assessment), PeerMark is a peer review program that encourages students to evaluate each other’s work. Students comment on assigned papers and answer scaled and free-form questions designed by the instructor. PeerMark does not allow you to assign point values or assign and export grades.

Contact the Center for a consultation on using these peer assessment tools.

Cho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2010). Student revision with peer and expert reviewing. Learning and Instruction , 20 (4), 328-338.

Kollar, I., & Fischer, F. (2010). Peer assessment as collaborative learning: A cognitive perspective. Learning and Instruction , 20 (4), 344-348.

The Teaching Center. (2009). Planning and guiding in-class peer review. Washington University in St. Louis. Retrieved from http://teachingcenter.wustl.edu/resources/writing-assignments-feedback/planning-and-guiding-in-class-peer-review/ .

Wasson, B., & Vold, V. (2012). Leveraging new media skills in a peer feedback tool. Internet and Higher Education , 15 (4), 1-10.

Xie, Y., Ke, F., & Sharma, P. (2008). The effect of peer feedback for blogging on college students’ reflective learning processes. Internet and Higher Education , 11 (1), 18-25.

van Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D., & van Merriënboer, J. (2010). Effective peer assessment processes: Research findings and future directions. Learning and Instruction , 20 (4), 270-279.

5 Questions For Creating a Peer-Review Rubric

November 20, 2018

Most instructors today use some form of a rubric to assess student writing or project-based-learning. Gone are the days of a professor writing a letter grade on the paper, and that being the only form of feedback the students receive. However, even when using a rubric, instructors may grade each rubric category in a holistic way, a result of their depth of knowledge of the topic and years of experience.

Learners, though, do not have the experience, knowledge, or ability to grade an essay or project in this kind of holistic way. For learners, the rubric needs to be a tool both for assessment and for learning. If they use a well-designed, objective peer-review rubric, learners can grade more like an experienced instructor, improve their critical analysis, and produce better finished products. In fact, research has shown that the reviewers improved the quality of their own work as a result of reviewing their peer’s work ( Wooley, et al., 2008 ).

Peer Rubric Distinctives

Unlike rubrics designed for instructor use, peer rubrics should be structured in a way to (1) assess a document, whether it be a writing assignment, video upload, presentation, podcast, or any type of project, and (2) help the reviewer learn how to think critically about the content of that document. For this reason, peer rubrics should be designed to teach students how to analyze the assignment in terms of specific, objective criteria and identify the quality of work at each level.

Using peer review often requires making changes to the rubric to transform it from an effective teacher rubric to an effective peer rubric . Using learner-friendly language, stating clear qualitative differences between rubric levels, and assessing one aspect of an assignment at a time will help your rubric become better for peer review.

Whether you are transforming an instructor rubric into a peer rubric or creating a peer rubric from scratch, here are some questions to help guide the process.

Questions to ask to Create an Effective Peer-Review Rubric

1. do the commenting prompts encourage students to give constructive criticism that brings out strengths and weaknesses in the document.

Design your commenting prompt to elicit the type of feedback that you want your students to write and receive. Encourage students to identify both strengths and weaknesses and to provide suggestions for improvement. Focus students’ attention on any specific areas on which you want them to provide feedback. Students appreciate the peer review process more when they receive useful, specific feedback that they can apply to future assignments.

For example, this commenting prompt on the content of a video presentation is designed to have the reviewer tell the presenter what they learned and what is not yet clear.

Content Commenting Prompt: What was something new that you learned or a new insight that you had as a result of this presentation? What in the presentation could have been clearer or more fully developed to enhance the content of this presentation?

2. How much reviewing can my students handle and still provide thoughtful, accurate feedback?

Reviewing several long documents with numerous commenting and rating prompts can lead to reviewer fatigue, where the reviewer starts to comment and rate carelessly. We recommend having multiple rating prompts but only one commenting prompt for each dimension (aspect or criteria being evaluated). For example, if there is a Content dimension for a peer review of a presentation, the rubric may include the following rating prompts: Depth of Content, Argument Structure, and Quality of Sources Used. If you are encouraging students to provide detailed, constructive feedback in the commenting prompt, having a small number of commenting prompts allows for thoughtful responses on all of the documents a student reviews.

3. Do my students understand all of the words and terms used in the rubric?

Make sure that the rubric only includes words that you know your students know. Remember that your students may not be familiar with technical or academic language. Spend time defining or describing the rubric terminology in class. It is easy to assume that all students will understand the language or know the difference between “competent” and “satisfactory,” but unless you have defined it in class, students’ interpretation may vary.

4. Does the rubric have clear, objective differences between each rating level?

While an instructor can quickly identify the difference between “poor” and “fair” work or “progressing” and “mastering” a skill, learners need more guidance as to what each of these levels means. For that reason, avoid using only one-word descriptors for your ratings and instead include a short description for each rating level.

In your description, use objective language that can be quantified or measured by a learner in the class. Identify what distinguishes one level from another in the assignment and use words of frequency, amount, quality, or proficiency to describe each level. Provide examples if you think there will be any confusion.

Here are some useful words in creating distinct dimension levels:

- Frequency : never, rarely, sometimes, often, always

- Amount : less than 2, 3-4, 5-6, 7+; no more than 50%, over half

- Quality : poorly, well, thoroughly; satisfactory, exemplar

- Proficiency : developing, emerging, mastery, expert

- Actions : lacks X; includes X; includes and develops X; includes, develops, and analyzes X

5. Does this rubric scaffold student learning as well as allow for accurate peer review?

It is important to meet learners where they are in their understanding of concepts in your course. Your rubrics for peer assessment should include all the information a student needs to assess that particular assignment and not assume that students have outside knowledge of that concept or skill. This may mean that you remove or rework concepts such as grammatical accuracy, depth of analysis, or ability to synthesize material from the peer review rubric until students have had greater exposure to it. Or, you may choose to focus on one quantifiable aspect of that concept (appropriate use of verb tenses, number of sources used, etc.) rather than asking students to assess that dimension in a holistic way.

Wooley, R., et al. “The effects of feedback elaboration on the giver of feedback.” 30th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. Vol. 5. 2008.

Peer Review With Digital Tools

I nteractions are a key component of student learning in online and face-to-face settings including student-instructor interactions, student-content interactions, and student-student interactions. Peer review is one type of student-student interaction that can build classroom community and deepen student learning (Nilson 2018). Feedback is a crucial part of learning but doesn’t only have to come from instructors –peer feedback can potentially save some time for instructors to do other important work with students (Brigati & Swann 2015). Guiding students to useful, productive peer feedback strengthens student performance and provides students with more feedback for learning growth.

How to Get Started

Best practices.

- Digital Tools

- Recording: Peer Review with Digital Tools and Moodle Workshop 2/2023

- Start the peer-review process with students by explaining the purpose of using peer review in your course. Stay positive and share why this is a worthwhile learning experience. Share that peer feedback should be descriptive (not evaluative) and the goal is for it to be formative, meaning that it will help change and develop future work that students submit.

- Will the peer feedback be graded or earn points in the class?

- What should the size of peer groups be and how many reviews should each assignment receive?

- Create a peer review feedback sheet or co-create wone with students –be sure it is aligned with goals/objectives for the assignment and any final evaluations that will occur.

- After collection, redistribute papers randomly along with a grading rubric. After students have evaluated the papers ask them to exchange with a neighbor, evaluate the new paper, and then compare notes.

- After completing an exam, have students compare and discuss answers with a partner. You may offer them the opportunity to submit a new answer, dividing points between the two.

- In a small class, ask students to bring one copy of their paper with their name on it and one or two copies without a name. Collect the “name” copy and redistribute the others for peer review. Provide feedback on all student papers. Collect the peer reviews and return papers to their authors.

- For group presentations, require the class to evaluate the group’s performance using a predetermined marking scheme.

- When working on group projects, have students evaluate each group member’s contribution to the project on a scale of 1-10. Require students to provide rationale for how and why they awarded points.

- Provide student models/examples of quality feedback and guidance for what students should do and what their feedback should “look like.” Align the feedback examples and expectations with learning objectives for students on the assignment requiring peer feedback. In the examples you share with students, model clear, constructive feedback with positive feedback as a first step. Note: the positive feedback is not praise about the student or person but specific to the task.

- Infographic example of “How to Give Awesome Feedback”

| Specific Feedback | Non-Specific Feedback |

|---|---|

| Your voice in your presentation was loud and the pacing made me able to follow your content but in the 2nd section I was confused by some of the terminology. Can you explain terms more or use terminology from class? | I didn’t get it. The presentation is confusing. |

| I found 2 piece of strong evidence from journals in your 2nd paragraph. They are connected to your topic sentence/subject but I think we are supposed to have three pieces of evidence | You didn’t do the assignment right. |

| Your infographic visuals are engaging to look at and the color-contrast makes them standout. | The infographic looked great! |

| The FAQ section of your website has two useful questions and answers but you should have at least five to ten. Maybe think about your website from the audience perspective to find more questions to answer or look at other FAQ examples. | There isn’t enough information or questions/answers. |

| The point you made during your speech about….made it clear that…… | It was a good speech. |

| I still have questions about …. But the section where you explained….is very clear. | This section was unclear, you should write more. |

- Find the thesis statement and three pieces of evidence aligned with the thesis statement

- Identify terminology from class used in the lab report

- Identify the strongest sentence in the conclusion

- Describe the organization of the methods and materials section of the lab report. Are their parts that confused you? If so, give suggestions for what might need clarification or expansion.

- Look for statements in the posting that directly connect to our class lectures and discussions. Point these out and ask for clarification if needed.

There are many peer review forms, worksheets, checklists, and so on available for different content areas and can be found by searching online. Here are some templates/examples:

- Essay peer review form with reviewer comment area and writer reflection/notes area

- A rubric to self-assess and peer-assess mathematical problem solving tasks of college students (article with peer checklist examples)

- Argumentative essay rubric with a column for peer feedback

- Group/team peer review checklist (make a copy to edit)

- RISE Model with open-ended/fill-in-the blank feedback (make a copy to edit)

- Peer Review Cover Sheet Example for a Presentation

- Presentation Rubric Checklist Rubric

- Choose a digital tool to support the peer review process — see the digital tool section (tab) for details. Recommended tools include PlayPosit Peer Review, Moodle Workshop Activity, Turnitin PeerMark, Google Workspace Tools

- Ideally allow students to keep revising and working with the peer feedback to make improvements in their work. This may mean fewer assignments get done in a class but students may show more growth and improvement in skills/deeper understanding of course concepts.

- Provide training to students and guided worksheets or reference materials to help them give better quality feedback. As part of this process, include examples and models of what effective feedback looks like.

- Explain the purpose of peer review to students, helping students realize the role of a peer-reviewer is to read and describe and not to evaluate or grade (Washington University Center for Teaching and Learning 2022). Consider asking students to analyze, react to, and describe their peers’ work rather than grade or evaluate.

- In guides, worksheets, or expectations ask students to give positive feedback first when describing the work of their peers (Nilson & Goodson 2018).

- In an online course, give a time estimate for how long student should expect to spend on a peer review. This could be part of a partnership contract for peer review (you can also consider having students design contracts together).

- Teaching Students to Evaluate Each Other (from Cornell University, Center for Teaching Innovation)

- Planning and Guiding In-Class Peer Review (from Washington University, Center for Teaching and Learning)

- Peer Feedback: Making it Meaningful (by Dr. Catlin Tucker)

Digital Tools: Feature Comparison

- Moodle Workshop

- Turnitin PeerMark

- Google Workspace

Moodle Workshop Activity: Peer Review Activity for Multiple Submission Types

Moodle’s workshop activity enables the collection, review and peer assessment of students’ work. Students can submit digital files (such as documents, slides, spreadsheets, or other attachments) or type text directly into a field using the text editor. Then, depending on instructor settings and guidance, students assess each other and give comments/feedback to their peers and/or give grades to their peers. After the peer-assessment window closes, instructors review the grades given to students, make any adjustments, and then post the grades to the Moodle gradebook.

Moodle Workshop has a complicated set up procedure and a bit of a learning curve for instructors and students. Therefore it is best if you plan on using it multiple times in a course. Workshop is particularly useful for large classes in which an instructor wants to get make grading more efficient by using students to grade their peers (note: there is research to show that peer grading can be valid and reliable).

If you only want students to provide feedback to each other and have an instructor provide the grade, be sure to use the “Comments” grading strategy when setting up the Workshop activity. Then have students turn in a revised copy of an assignment in an separate Moodle assignment activity so the instructor can provide the final grade.

Student submissions can be assessed by their peers in multiple ways depending on how an instructor sets up the activity. Peers can use a “checklist” of criteria or a rubric with specific quality indicators – both must be defined by the instructor. Students are given the opportunity to assess one or more of their peers’ submissions. Submissions and reviewers may be anonymous. Students obtain two grades in a workshop activity — a grade for their submission and a grade for their assessment of their peers’ submissions. Both grades are recorded in the Moodle Gradebook.

- Moodle Docs: Workshop Activity with video tutorial (Moodle 4)

- Moodle Docs: Using Workshop with step-by-step phase directions (Moodle 4 )

- Moodle Forum for Instructors on Using the Workshop Activity –online discussion with help and other instructors who use Workshop

- YouTube Playlist: Moodle Workshop Activity

- Example workshop with data (Log in with username teacher /password moodle and explore the grading and phases of a completed workshop on the Moodle School demo site.)

- Workshop Guide with Grade Adjustment Suggestions

Turnitin PeerMark: Peer Review Tool for Writing Assignments/Papers

PeerMark is a peer review assignment tool for essays, papers, and other writing assignments. Instructors can create and manage PeerMark assignments that allow students to read, review, and evaluate one or many papers submitted by their classmates. Reviews can be anonymous.

Instructors will create a Turnitin Assignment 2 within Moodle and then add a PeerMark assignment to the original assignment. After students have submitted writing assignments they will be given peer’s submissions to provide feedback. An instructor can determine pairings/groups for peer review or allow them to be assigned by the Turnitin system. An instructor can provide questions to guide the review – these questions can be open-ended or associated with points. Inline and pop-up comments can also be added by peers. Note: if instructors want to assign grades to students based on their work doing peer reviews, those grades will have to be added to Moodle manually.

NOTE: Turnitin does not work on a mobile device

- Turnitin PeerMark Assignments in Moodle: Instructor Guide

- Turnitin PeerMark Guide to Share with Students

- YouTube Playlist (currently being updated)

- About PeerMark™ assignments

Google Workspace Tools: Peer Reviews not Synced with Moodle

Each of the primary Google Workspace Tools: Docs, Slides, Sheets allow for comments and assigning tasks to students. These features can help students with peer review as can annotating text by highlighting and underlining with different colors. In Google Docs, additional peer review tools include the ability to add a watermark i.e. “Draft” and use the “Suggesting” mode to make changes directly to a document that can be accepted or declined by the author/owner of the document.

For workflow, students can also create a tickable checkbox/schedule for peer review at the top of the document. Instructors can also create templates for students to use when drafting that have built in headings, question, etc. for peers to consider when reviewing — ask students to make a copy of a document or you can create a “forced copy” version of a document. Instructors can also use shared folders to organize peer reviews. Using Google Workspace tools for peer review will not automatically add grades to Moodle –instructors would need to manually add grades to Moodle.

Features within Google Tools:

- Suggest edits in Google Docs – Computer – Docs Editors Help

- Comments and Action Items in Google Docs, Sheets, and Slides

- How to Create a Checklist in Google Docs

- Process Suggestion: Guiding Student Peer Review – Google Drive

- Jamboard Process Suggestion (students add work to a Jamboard and send it to their peers)

- Manage Notifications

- Google Forms: Students can send Google Forms to peers – -instructors can create Google Form templates for students to use ( example form and suggested process )

Guidance Using Google Tools in Conjunction with Moodle:

- Google Groups : Create a class folder in Drive and then share it or group folders with students –groups can be managed through Wolfware

- Use a Discussion Forum/Board: Students submit work and use the forum to give each other feedback — note: feedback will be viewable to peers. Instructors can also create forums for small peer groups. A rubric can be attached to the Discussion Forum via “Advanced Grading”

- Moodle Assignments: Students independently use Google commenting, suggestion, annotation tools and upload a marked copy to a Moodle Assignment. A rubric can be attached to the assignment via “Advanced Grading”

- Google Assignments: Allows students to turn in work directly from Google Drive and it controls the sharing/access to documents but does not have a built in peer/collaboration feature. Use the template option and ask students to turn in the work with the peer comments. For more on Google Assignments in general use this instructor guide.

- Manual Grading in Moodle: If students are using a Google Form or shared documents in Drive folders and you want to add a grade to Moodle, add a grade item and enter the grades manually. Instructors can add multiple grade items for the creator/writer’s work and for the peers who are reviewing.

Video Project Student Submission and Peer Review

PlayPosit is an interactive video creator allowing instructors to overlay questions, discussion, web content, and other interactions on top of a video creating opportunities for students to interact with course content.

The Peer Review feature allows students to upload videos and then provide feedback on peer-submitted videos and get peer feedback for their own work. This tool is particularly useful for performance-based assignments.

Students can submit a recording of their own performance in a speech, presentation, micro-teaching session, model job interview, artistic performance, etc. and receive peer feedback on that work. Instructors can provide different levels of guidance in how students should provide feedback and feedback can be anonymous. PlayPosit communicates with the Moodle Gradebook through a “completion” grade just for uploading a video and giving comments OR through a graded assignment in which the instructor gives students comments and/or feedback via an embedded rubric.

- PlayPosit Peer Review Instructor Set Up in Moodle at NC State

- Grading a PlayPosit Peer Review in Moodle at NC State: Instructors

- Completing a PlayPosit Peer Review Assignment in Moodle at NC State: Students

- PlayPosit Peer Review Guide for Instructors

- PlayPosit Peer Review Video for Instructors

Panopto is the NC State enterprise tool for recording, storing, and sharing videos and audio. Both students and instructors can record in Panopto and then share their work with others within and outside of NC State.

Instructors can add a “Panopto Student Submission” activity in a Moodle course. This will allow students to add a video from Panopto (they can record within Panopto or upload a video to Panopto). However, in the Panopto Student Submission activity type, student-submitted videos are only viewable to the instructor.

If instructors want students to view each others work and give feedback, they can create and use the “Assignment Folder” feature built into Panopto.

- Panopto Assignment Folders for Peer Feedback

Research: Books & Articles