- Study Protocol

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2024

Learning effect of online versus onsite education in health and medical scholarship – protocol for a cluster randomized trial

- Rie Raffing 1 ,

- Lars Konge 2 &

- Hanne Tønnesen 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 927 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

123 Accesses

Metrics details

The disruption of health and medical education by the COVID-19 pandemic made educators question the effect of online setting on students’ learning, motivation, self-efficacy and preference. In light of the health care staff shortage online scalable education seemed relevant. Reviews on the effect of online medical education called for high quality RCTs, which are increasingly relevant with rapid technological development and widespread adaption of online learning in universities. The objective of this trial is to compare standardized and feasible outcomes of an online and an onsite setting of a research course regarding the efficacy for PhD students within health and medical sciences: Primarily on learning of research methodology and secondly on preference, motivation, self-efficacy on short term and academic achievements on long term. Based on the authors experience with conducting courses during the pandemic, the hypothesis is that student preferred onsite setting is different to online setting.

Cluster randomized trial with two parallel groups. Two PhD research training courses at the University of Copenhagen are randomized to online (Zoom) or onsite (The Parker Institute, Denmark) setting. Enrolled students are invited to participate in the study. Primary outcome is short term learning. Secondary outcomes are short term preference, motivation, self-efficacy, and long-term academic achievements. Standardized, reproducible and feasible outcomes will be measured by tailor made multiple choice questionnaires, evaluation survey, frequently used Intrinsic Motivation Inventory, Single Item Self-Efficacy Question, and Google Scholar publication data. Sample size is calculated to 20 clusters and courses are randomized by a computer random number generator. Statistical analyses will be performed blinded by an external statistical expert.

Primary outcome and secondary significant outcomes will be compared and contrasted with relevant literature. Limitations include geographical setting; bias include lack of blinding and strengths are robust assessment methods in a well-established conceptual framework. Generalizability to PhD education in other disciplines is high. Results of this study will both have implications for students and educators involved in research training courses in health and medical education and for the patients who ultimately benefits from this training.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05736627. SPIRIT guidelines are followed.

Peer Review reports

Medical education was utterly disrupted for two years by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the midst of rearranging courses and adapting to online platforms we, with lecturers and course managers around the globe, wondered what the conversion to online setting did to students’ learning, motivation and self-efficacy [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. What the long-term consequences would be [ 4 ] and if scalable online medical education should play a greater role in the future [ 5 ] seemed relevant and appealing questions in a time when health care professionals are in demand. Our experience of performing research training during the pandemic was that although PhD students were grateful for courses being available, they found it difficult to concentrate related to the long screen hours. We sensed that most students preferred an onsite setting and perceived online courses a temporary and inferior necessity. The question is if this impacted their learning?

Since the common use of the internet in medical education, systematic reviews have sought to answer if there is a difference in learning effect when taught online compared to onsite. Although authors conclude that online learning may be equivalent to onsite in effect, they agree that studies are heterogeneous and small [ 6 , 7 ], with low quality of the evidence [ 8 , 9 ]. They therefore call for more robust and adequately powered high-quality RCTs to confirm their findings and suggest that students’ preferences in online learning should be investigated [ 7 , 8 , 9 ].

This uncovers two knowledge gaps: I) High-quality RCTs on online versus onsite learning in health and medical education and II) Studies on students’ preferences in online learning.

Recently solid RCTs have been performed on the topic of web-based theoretical learning of research methods among health professionals [ 10 , 11 ]. However, these studies are on asynchronous courses among medical or master students with short term outcomes.

This uncovers three additional knowledge gaps: III) Studies on synchronous online learning IV) among PhD students of health and medical education V) with long term measurement of outcomes.

The rapid technological development including artificial intelligence (AI) and widespread adaption as well as application of online learning forced by the pandemic, has made online learning well-established. It represents high resolution live synchronic settings which is available on a variety of platforms with integrated AI and options for interaction with and among students, chat and break out rooms, and exterior digital tools for teachers [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Thus, investigating online learning today may be quite different than before the pandemic. On one hand, it could seem plausible that this technological development would make a difference in favour of online learning which could not be found in previous reviews of the evidence. On the other hand, the personal face-to-face interaction during onsite learning may still be more beneficial for the learning process and combined with our experience of students finding it difficult to concentrate when online during the pandemic we hypothesize that outcomes of the onsite setting are different from the online setting.

To support a robust study, we design it as a cluster randomized trial. Moreover, we use the well-established and widely used Kirkpatrick’s conceptual framework for evaluating learning as a lens to assess our outcomes [ 15 ]. Thus, to fill the above-mentioned knowledge gaps, the objective of this trial is to compare a synchronous online and an in-person onsite setting of a research course regarding the efficacy for PhD students within the health and medical sciences:

Primarily on theoretical learning of research methodology and

Secondly on

◦ Preference, motivation, self-efficacy on short term

◦ Academic achievements on long term

Trial design

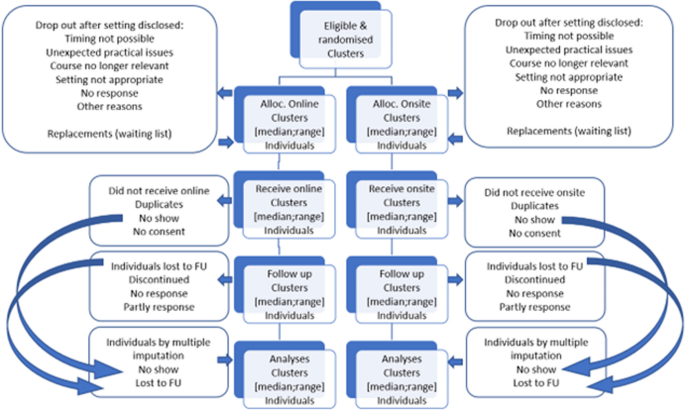

This study protocol covers synchronous online and in-person onsite setting of research courses testing the efficacy for PhD students. It is a two parallel arms cluster randomized trial (Fig. 1 ).

Consort flow diagram

The study measures baseline and post intervention. Baseline variables and knowledge scores are obtained at the first day of the course, post intervention measurement is obtained the last day of the course (short term) and monthly for 24 months (long term).

Randomization is stratified giving 1:1 allocation ratio of the courses. As the number of participants within each course might differ, the allocation ratio of participants in the study will not fully be equal and 1:1 balanced.

Study setting

The study site is The Parker Institute at Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. From here the courses are organized and run online and onsite. The course programs and time schedules, the learning objective, the course management, the lecturers, and the delivery are identical in the two settings. The teachers use the same introductory presentations followed by training in break out groups, feed-back and discussions. For the online group, the setting is organized as meetings in the online collaboration tool Zoom® [ 16 ] using the basic available technicalities such as screen sharing, chat function for comments, and breakout rooms and other basics digital tools if preferred. The online version of the course is synchronous with live education and interaction. For the onsite group, the setting is the physical classroom at the learning facilities at the Parker Institute. Coffee and tea as well as simple sandwiches and bottles of water, which facilitate sociality, are available at the onsite setting. The participants in the online setting must get their food and drink by themselves, but online sociality is made possible by not closing down the online room during the breaks. The research methodology courses included in the study are “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research”, (see course programme in appendix 1) and “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” [ 17 ] (see course programme in appendix 2). The two courses both have 12 seats and last either three or three and a half days resulting in 2.2 and 2.6 ECTS credits, respectively. They are offered by the PhD School of the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. Both courses are available and covered by the annual tuition fee for all PhD students enrolled at a Danish university.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for participants: All PhD students enrolled on the PhD courses participate after informed consent: “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” at the PhD School of the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Exclusion criteria for participants: Declining to participate and withdrawal of informed consent.

Informed consent

The PhD students at the PhD School at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen participate after informed consent, taken by the daily project leader, allowing evaluation data from the course to be used after pseudo-anonymization in the project. They are informed in a welcome letter approximately three weeks prior to the course and again in the introduction the first course day. They register their consent on the first course day (Appendix 3). Declining to participate in the project does not influence their participation in the course.

Interventions

Online course settings will be compared to onsite course settings. We test if the onsite setting is different to online. Online learning is increasing but onsite learning is still the preferred educational setting in a medical context. In this case onsite learning represents “usual care”. The online course setting is meetings in Zoom using the technicalities available such as chat and breakout rooms. The onsite setting is the learning facilities, at the Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, The Capital Region, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The course settings are not expected to harm the participants, but should a request be made to discontinue the course or change setting this will be met, and the participant taken out of the study. Course participants are allowed to take part in relevant concomitant courses or other interventions during the trial.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions

Course participants are motivated to complete the course irrespectively of the setting because it bears ECTS-points for their PhD education and adds to the mandatory number of ECTS-points. Thus, we expect adherence to be the same in both groups. However, we monitor their presence in the course and allocate time during class for testing the short-term outcomes ( motivation, self-efficacy, preference and learning). We encourage and, if necessary, repeatedly remind them to register with Google Scholar for our testing of the long-term outcome (academic achievement).

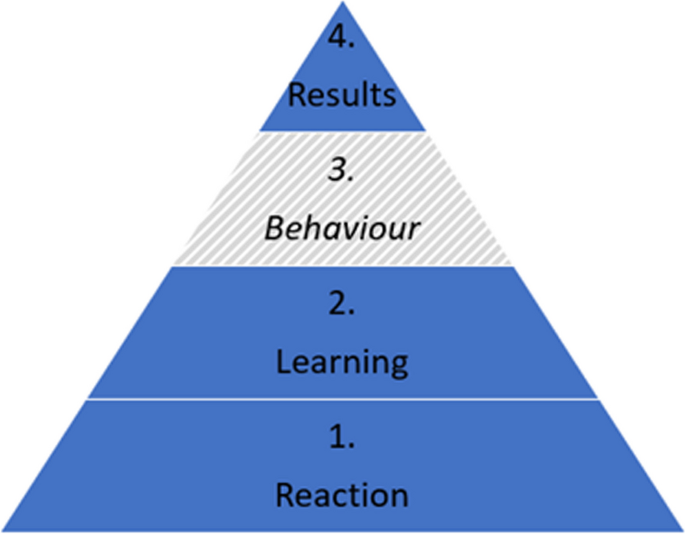

Outcomes are related to the Kirkpatrick model for evaluating learning (Fig. 2 ) which divides outcomes into four different levels; Reaction which includes for example motivation, self-efficacy and preferences, Learning which includes knowledge acquisition, Behaviour for practical application of skills when back at the job (not included in our outcomes), and Results for impact for end-users which includes for example academic achievements in the form of scientific articles [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

The Kirkpatrick model

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is short term learning (Kirkpatrick level 2).

Learning is assessed by a Multiple-Choice Questionnaire (MCQ) developed prior to the RCT specifically for this setting (Appendix 4). First the lecturers of the two courses were contacted and asked to provide five multiple choice questions presented as a stem with three answer options; one correct answer and two distractors. The questions should be related to core elements of their teaching under the heading of research training. The questions were set up to test the cognition of the students at the levels of "Knows" or "Knows how" according to Miller's Pyramid of Competence and not their behaviour [ 21 ]. Six of the course lecturers responded and out of this material all the questions which covered curriculum of both courses were selected. It was tested on 10 PhD students and within the lecturer group, revised after an item analysis and English language revised. The MCQ ended up containing 25 questions. The MCQ is filled in at baseline and repeated at the end of the course. The primary outcomes based on the MCQ is estimated as the score of learning calculated as number of correct answers out of 25 after the course. A decrease of points of the MCQ in the intervention groups denotes a deterioration of learning. In the MCQ the minimum score is 0 and 25 is maximum, where 19 indicates passing the course.

Furthermore, as secondary outcome, this outcome measurement will be categorized as binary outcome to determine passed/failed of the course defined by 75% (19/25) correct answers.

The learning score will be computed on group and individual level and compared regarding continued outcomes by the Mann–Whitney test comparing the learning score of the online and onsite groups. Regarding the binomial outcome of learning (passed/failed) data will be analysed by the Fisher’s exact test on an intention-to-treat basis between the online and onsite. The results will be presented as median and range and as mean and standard deviations, for possible future use in meta-analyses.

Secondary outcomes

Motivation assessment post course: Motivation level is measured by the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) Scale [ 22 ] (Appendix 5). The IMI items were randomized by random.org on the 4th of August 2022. It contains 12 items to be assessed by the students on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 is “Not at all true”, 4 is “Somewhat true” and 7 is “Very true”. The motivation score will be computed on group and individual level and will then be tested by the Mann–Whitney of the online and onsite group.

Self-efficacy assessment post course: Self-efficacy level is measured by a single-item measure developed and validated by Williams and Smith [ 23 ] (Appendix 6). It is assessed by the students on a scale from 1–10 where 1 is “Strongly disagree” and 10 is “Strongly agree”. The self-efficacy score will be computed on group and individual level and tested by a Mann–Whitney test to compare the self-efficacy score of the online and onsite group.

Preference assessment post course: Preference is measured as part of the general course satisfaction evaluation with the question “If you had the option to choose, which form would you prefer this course to have?” with the options “onsite form” and “online form”.

Academic achievement assessment is based on 24 monthly measurements post course of number of publications, number of citations, h-index, i10-index. This data is collected through the Google Scholar Profiles [ 24 ] of the students as this database covers most scientific journals. Associations between onsite/online and long-term academic will be examined with Kaplan Meyer and log rank test with a significance level of 0.05.

Participant timeline

Enrolment for the course at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, becomes available when it is published in the course catalogue. In the course description the course location is “To be announced”. Approximately 3–4 weeks before the course begins, the participant list is finalized, and students receive a welcome letter containing course details, including their allocation to either the online or onsite setting. On the first day of the course, oral information is provided, and participants provide informed consent, baseline variables, and base line knowledge scores.

The last day of scheduled activities the following scores are collected, knowledge, motivation, self-efficacy, setting preference, and academic achievement. To track students' long term academic achievements, follow-ups are conducted monthly for a period of 24 months, with assessments occurring within one week of the last course day (Table 1 ).

Sample size

The power calculation is based on the main outcome, theoretical learning on short term. For the sample size determination, we considered 12 available seats for participants in each course. To achieve statistical power, we aimed for 8 clusters in both online and onsite arms (in total 16 clusters) to detect an increase in learning outcome of 20% (learning outcome increase of 5 points). We considered an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.02, a standard deviation of 10, a power of 80%, and a two-sided alpha level of 5%. The Allocation Ratio was set at 1, implying an equal number of subjects in both online and onsite group.

Considering a dropout up to 2 students per course, equivalent to 17%, we determined that a total of 112 participants would be needed. This calculation factored in 10 clusters of 12 participants per study arm, which we deemed sufficient to assess any changes in learning outcome.

The sample size was estimated using the function n4means from the R package CRTSize [ 25 ].

Recruitment

Participants are PhD students enrolled in 10 courses of “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and 10 courses of “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” at the PhD School of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Assignment of interventions: allocation

Randomization will be performed on course-level. The courses are randomized by a computer random number generator [ 26 ]. To get a balanced randomization per year, 2 sets with 2 unique random integers in each, taken from the 1–4 range is requested.

The setting is not included in the course catalogue of the PhD School and thus allocation to online or onsite is concealed until 3–4 weeks before course commencement when a welcome letter with course information including allocation to online or onsite setting is distributed to the students. The lecturers are also informed of the course setting at this time point. If students withdraw from the course after being informed of the setting, a letter is sent to them enquiring of the reason for withdrawal and reason is recorded (Appendix 7).

The allocation sequence is generated by a computer random number generator (random.org). The participants and the lecturers sign up for the course without knowing the course setting (online or onsite) until 3–4 weeks before the course.

Assignment of interventions: blinding

Due to the nature of the study, it is not possible to blind trial participants or lecturers. The outcomes are reported by the participants directly in an online form, thus being blinded for the outcome assessor, but not for the individual participant. The data collection for the long-term follow-up regarding academic achievements is conducted without blinding. However, the external researcher analysing the data will be blinded.

Data collection and management

Data will be collected by the project leader (Table 1 ). Baseline variables and post course knowledge, motivation, and self-efficacy are self-reported through questionnaires in SurveyXact® [ 27 ]. Academic achievements are collected through Google Scholar profiles of the participants.

Given that we are using participant assessments and evaluations for research purposes, all data collection – except for monthly follow-up of academic achievements after the course – takes place either in the immediate beginning or ending of the course and therefore we expect participant retention to be high.

Data will be downloaded from SurveyXact and stored in a locked and logged drive on a computer belonging to the Capital Region of Denmark. Only the project leader has access to the data.

This project conduct is following the Danish Data Protection Agency guidelines of the European GDPR throughout the trial. Following the end of the trial, data will be stored at the Danish National Data Archive which fulfil Danish and European guidelines for data protection and management.

Statistical methods

Data is anonymized and blinded before the analyses. Analyses are performed by a researcher not otherwise involved in the inclusion or randomization, data collection or handling. All statistical tests will be testing the null hypotheses assuming the two arms of the trial being equal based on corresponding estimates. Analysis of primary outcome on short-term learning will be started once all data has been collected for all individuals in the last included course. Analyses of long-term academic achievement will be started at end of follow-up.

Baseline characteristics including both course- and individual level information will be presented. Table 2 presents the available data on baseline.

We will use multivariate analysis for identification of the most important predictors (motivation, self-efficacy, sex, educational background, and knowledge) for best effect on short and long term. The results will be presented as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The results will be considered significant if CI does not include the value one.

All data processing and analyses were conducted using R statistical software version 4.1.0, 2021–05-18 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

If possible, all analysis will be performed for “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and for “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” separately.

Primary analyses will be handled with the intention-to-treat approach. The analyses will include all individuals with valid data regardless of they did attend the complete course. Missing data will be handled with multiple imputation [ 28 ] .

Upon reasonable request, public assess will be granted to protocol, datasets analysed during the current study, and statistical code Table 3 .

Oversight, monitoring, and adverse events

This project is coordinated in collaboration between the WHO CC (DEN-62) at the Parker Institute, CAMES, and the PhD School at the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. The project leader runs the day-to-day support of the trial. The steering committee of the trial includes principal investigators from WHO CC (DEN-62) and CAMES and the project leader and meets approximately three times a year.

Data monitoring is done on a daily basis by the project leader and controlled by an external independent researcher.

An adverse event is “a harmful and negative outcome that happens when a patient has been provided with medical care” [ 29 ]. Since this trial does not involve patients in medical care, we do not expect adverse events. If participants decline taking part in the course after receiving the information of the course setting, information on reason for declining is sought obtained. If the reason is the setting this can be considered an unintended effect. Information of unintended effects of the online setting (the intervention) will be recorded. Participants are encouraged to contact the project leader with any response to the course in general both during and after the course.

The trial description has been sent to the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (VEK) (21041907), which assessed it as not necessary to notify and that it could proceed without permission from VEK according to the Danish law and regulation of scientific research. The trial is registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (Privacy) (P-2022–158). Important protocol modification will be communicated to relevant parties as well as VEK, the Joint Regional Information Security and Clinicaltrials.gov within an as short timeframe as possible.

Dissemination plans

The results (positive, negative, or inconclusive) will be disseminated in educational, scientific, and clinical fora, in international scientific peer-reviewed journals, and clinicaltrials.gov will be updated upon completion of the trial. After scientific publication, the results will be disseminated to the public by the press, social media including the website of the hospital and other organizations – as well as internationally via WHO CC (DEN-62) at the Parker Institute and WHO Europe.

All authors will fulfil the ICMJE recommendations for authorship, and RR will be first author of the articles as a part of her PhD dissertation. Contributors who do not fulfil these recommendations will be offered acknowledgement in the article.

This cluster randomized trial investigates if an onsite setting of a research course for PhD students within the health and medical sciences is different from an online setting. The outcomes measured are learning of research methodology (primary), preference, motivation, and self-efficacy (secondary) on short term and academic achievements (secondary) on long term.

The results of this study will be discussed as follows:

Discussion of primary outcome

Primary outcome will be compared and contrasted with similar studies including recent RCTs and mixed-method studies on online and onsite research methodology courses within health and medical education [ 10 , 11 , 30 ] and for inspiration outside the field [ 31 , 32 ]: Tokalic finds similar outcomes for online and onsite, Martinic finds that the web-based educational intervention improves knowledge, Cheung concludes that the evidence is insufficient to say that the two modes have different learning outcomes, Kofoed finds online setting to have negative impact on learning and Rahimi-Ardabili presents positive self-reported student knowledge. These conflicting results will be discussed in the context of the result on the learning outcome of this study. The literature may change if more relevant studies are published.

Discussion of secondary outcomes

Secondary significant outcomes are compared and contrasted with similar studies.

Limitations, generalizability, bias and strengths

It is a limitation to this study, that an onsite curriculum for a full day is delivered identically online, as this may favour the onsite course due to screen fatigue [ 33 ]. At the same time, it is also a strength that the time schedules are similar in both settings. The offer of coffee, tea, water, and a plain sandwich in the onsite course may better facilitate the possibility for socializing. Another limitation is that the study is performed in Denmark within a specific educational culture, with institutional policies and resources which might affect the outcome and limit generalization to other geographical settings. However, international students are welcome in the class.

In educational interventions it is generally difficult to blind participants and this inherent limitation also applies to this trial [ 11 ]. Thus, the participants are not blinded to their assigned intervention, and neither are the lecturers in the courses. However, the external statistical expert will be blinded when doing the analyses.

We chose to compare in-person onsite setting with a synchronous online setting. Therefore, the online setting cannot be expected to generalize to asynchronous online setting. Asynchronous delivery has in some cases showed positive results and it might be because students could go back and forth through the modules in the interface without time limit [ 11 ].

We will report on all the outcomes defined prior to conducting the study to avoid selective reporting bias.

It is a strength of the study that it seeks to report outcomes within the 1, 2 and 4 levels of the Kirkpatrick conceptual framework, and not solely on level 1. It is also a strength that the study is cluster randomized which will reduce “infections” between the two settings and has an adequate power calculated sample size and looks for a relevant educational difference of 20% between the online and onsite setting.

Perspectives with implications for practice

The results of this study may have implications for the students for which educational setting they choose. Learning and preference results has implications for lecturers, course managers and curriculum developers which setting they should plan for the health and medical education. It may also be of inspiration for teaching and training in other disciplines. From a societal perspective it also has implications because we will know the effect and preferences of online learning in case of a future lock down.

Future research could investigate academic achievements in online and onsite research training on the long run (Kirkpatrick 4); the effect of blended learning versus online or onsite (Kirkpatrick 2); lecturers’ preferences for online and onsite setting within health and medical education (Kirkpatrick 1) and resource use in synchronous and asynchronous online learning (Kirkpatrick 5).

Trial status

This trial collected pilot data from August to September 2021 and opened for inclusion in January 2022. Completion of recruitment is expected in April 2024 and long-term follow-up in April 2026. Protocol version number 1 03.06.2022 with amendments 30.11.2023.

Availability of data and materials

The project leader will have access to the final trial dataset which will be available upon reasonable request. Exception to this is the qualitative raw data that might contain information leading to personal identification.

Abbreviations

Artificial Intelligence

Copenhagen academy for medical education and simulation

Confidence interval

Coronavirus disease

European credit transfer and accumulation system

International committee of medical journal editors

Intrinsic motivation inventory

Multiple choice questionnaire

Doctor of medicine

Masters of sciences

Randomized controlled trial

Scientific ethical committee of the Capital Region of Denmark

WHO Collaborating centre for evidence-based clinical health promotion

Samara M, Algdah A, Nassar Y, Zahra SA, Halim M, Barsom RMM. How did online learning impact the academic. J Technol Sci Educ. 2023;13(3):869–85.

Article Google Scholar

Nejadghaderi SA, Khoshgoftar Z, Fazlollahi A, Nasiri MJ. Medical education during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: an umbrella review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1358084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1358084 .

Madi M, Hamzeh H, Abujaber S, Nawasreh ZH. Have we failed them? Online learning self-efficacy of physiotherapy students during COVID-19 pandemic. Physiother Res Int. 2023;5:e1992. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1992 .

Torda A. How COVID-19 has pushed us into a medical education revolution. Intern Med J. 2020;50(9):1150–3.

Alhat S. Virtual Classroom: A Future of Education Post-COVID-19. Shanlax Int J Educ. 2020;8(4):101–4.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Internet-based learning in the health professions: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1181–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.10.1181 .

Pei L, Wu H. Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1666538. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1666538 .

Richmond H, Copsey B, Hall AM, Davies D, Lamb SE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of online versus alternative methods for training licensed health care professionals to deliver clinical interventions. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1047-4 .

George PP, Zhabenko O, Kyaw BM, Antoniou P, Posadzki P, Saxena N, Semwal M, Tudor Car L, Zary N, Lockwood C, Car J. Online Digital Education for Postregistration Training of Medical Doctors: Systematic Review by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e13269. https://doi.org/10.2196/13269 .

Tokalić R, Poklepović Peričić T, Marušić A. Similar Outcomes of Web-Based and Face-to-Face Training of the GRADE Approach for the Certainty of Evidence: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e43928. https://doi.org/10.2196/43928 .

Krnic Martinic M, Čivljak M, Marušić A, Sapunar D, Poklepović Peričić T, Buljan I, et al. Web-Based Educational Intervention to Improve Knowledge of Systematic Reviews Among Health Science Professionals: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(8): e37000.

https://www.mentimeter.com/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

https://www.sendsteps.com/en/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

https://da.padlet.com/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Zackoff MW, Real FJ, Abramson EL, Li STT, Klein MD, Gusic ME. Enhancing Educational Scholarship Through Conceptual Frameworks: A Challenge and Roadmap for Medical Educators. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(2):135–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.08.003 .

https://zoom.us/ . Accessed 20 Aug 2024.

Raffing R, Larsen S, Konge L, Tønnesen H. From Targeted Needs Assessment to Course Ready for Implementation-A Model for Curriculum Development and the Course Results. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032529 .

https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/the-kirkpatrick-model/ . Accessed 12 Dec 2023.

Smidt A, Balandin S, Sigafoos J, Reed VA. The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(3):266–74.

Campbell K, Taylor V, Douglas S. Effectiveness of online cancer education for nurses and allied health professionals; a systematic review using kirkpatrick evaluation framework. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(2):339–56.

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–7.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68 .

Williams GM, Smith AP. Using single-item measures to examine the relationships between work, personality, and well-being in the workplace. Psychology. 2016;07(06):753–67.

https://scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/citations.html . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Rotondi MA. CRTSize: sample size estimation functions for cluster randomized trials. R package version 1.0. 2015. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=CRTSize .

Random.org. Available from: https://www.random.org/

https://rambollxact.dk/surveyxact . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ (Online). 2009;339:157–60.

Google Scholar

Skelly C, Cassagnol M, Munakomi S. Adverse Events. StatPearls Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558963/ .

Rahimi-Ardabili H, Spooner C, Harris MF, Magin P, Tam CWM, Liaw ST, et al. Online training in evidence-based medicine and research methods for GP registrars: a mixed-methods evaluation of engagement and impact. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8439372/pdf/12909_2021_Article_2916.pdf .

Cheung YYH, Lam KF, Zhang H, Kwan CW, Wat KP, Zhang Z, et al. A randomized controlled experiment for comparing face-to-face and online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Educ. 2023;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1160430 .

Kofoed M, Gebhart L, Gilmore D, Moschitto R. Zooming to Class?: Experimental Evidence on College Students' Online Learning During Covid-19. SSRN Electron J. 2021;IZA Discussion Paper No. 14356.

Mutlu Aİ, Yüksel M. Listening effort, fatigue, and streamed voice quality during online university courses. Logop Phoniatr Vocol :1–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/14015439.2024.2317789

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the students who make their evaluations available for this trial and MSc (Public Health) Mie Sylow Liljendahl for statistical support.

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University The Parker Institute, which hosts the WHO CC (DEN-62), receives a core grant from the Oak Foundation (OCAY-18–774-OFIL). The Oak Foundation had no role in the design of the study or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

WHO Collaborating Centre (DEN-62), Clinical Health Promotion Centre, The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg & Frederiksberg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, 2400, Denmark

Rie Raffing & Hanne Tønnesen

Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation (CAMES), Centre for HR and Education, The Capital Region of Denmark, Copenhagen, 2100, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RR, LK and HT have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; RR to the acquisition of data, and RR, LK and HT to the interpretation of data; RR has drafted the work and RR, LK, and HT have substantively revised it AND approved the submitted version AND agreed to be personally accountable for their own contributions as well as ensuring that any questions which relates to the accuracy or integrity of the work are adequately investigated, resolved and documented.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rie Raffing .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics has assessed the study Journal-nr.:21041907 (Date: 21–09-2021) without objections or comments. The study has been approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency Journal-nr.: P-2022–158 (Date: 04.05.2022).

All PhD students participate after informed consent. They can withdraw from the study at any time without explanations or consequences for their education. They will be offered information of the results at study completion. There are no risks for the course participants as the measurements in the course follow routine procedure and they are not affected by the follow up in Google Scholar. However, the 15 min of filling in the forms may be considered inconvenient.

The project will follow the GDPR and the Joint Regional Information Security Policy. Names and ID numbers are stored on a secure and logged server at the Capital Region Denmark to avoid risk of data leak. All outcomes are part of the routine evaluation at the courses, except the follow up for academic achievement by publications and related indexes. However, the publications are publicly available per se.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1., supplementary material 2., supplementary material 3., supplementary material 4., supplementary material 5., supplementary material 6., supplementary material 7., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Raffing, R., Konge, L. & Tønnesen, H. Learning effect of online versus onsite education in health and medical scholarship – protocol for a cluster randomized trial. BMC Med Educ 24 , 927 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05915-z

Download citation

Received : 25 March 2024

Accepted : 14 August 2024

Published : 26 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05915-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Self-efficacy

- Achievements

- Health and Medical education

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

August 29, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

Interprofessional training in health sciences education has a lasting impact on practice, study shows

by University of Southern California

Geriatrics experts have long known that collaboration is key to delivering quality, patient-centered care to older adults.

That's why USC's Interprofessional Education and Collaboration for Geriatrics (IECG) trains up to 150 students annually from seven health professions to teach the importance of teamwork in meeting the complex needs of the elderly.

Now, a study published in the Journal of Interprofessional Care highlights the long-term impact of IECG on USC health sciences graduates.

Researchers surveyed graduates one to three years after completing IECG to assess how the program influenced their practice. The findings were significant: 81% of the graduates worked on interprofessional teams, 80% reported that IECG had a major impact on their practice, and all confirmed they regularly used the assessment tools learned in the program.

"We've really seen over the last decade that this program consistently improves health profession graduate students' interprofessional knowledge and attitudes and also helps them prepare them for collaborative practice ," said Dawn Joosten-Hagye, first author on the study and professor of social work at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

"This is one of the first studies to actually look at how students sustain their interprofessional education training."

The program was initiated 14 years ago by study co-author Jo Marie Reilly, a professor of clinical family medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, who saw the need for an innovative training model focused on the complex health care needs of older adults.

The collaborative effort has since included students from dentistry, medicine, occupational therapy , pharmacy, physical therapy , gerontology, psychology, and social work.

Looking forward, the study's authors believe the IECG model could be adapted to address the needs of other populations with complex health care needs, such as people with disabilities, cancer patients, and children.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Machine learning predicts which patients will continue taking opioids after hand surgery

16 minutes ago

Study describes a new molecular pathway involved in the control of reproduction

37 minutes ago

Machine learning helps identify rheumatoid arthritis subtypes

Immune protection against tuberculosis reinfection driven by cells that dampen lung inflammation, shows study

Girls with mental health conditions have lower HPV vaccination coverage

Mankai plant found to reduce post-meal sugar levels in diabetics

2 hours ago

Unique chicken line advances research on autoimmune disease that affects humans

Navigating the digestive tract: Study offers first detailed map of the small intestine

Dental researchers develop innovative sleep apnea model to find answers to chronic pain

Smart mask monitors breath for signs of health

Related stories.

Brief teacher training found to better prepare medical students for patient education and communication

Dec 15, 2023

Pipeline program at medical school boosts primary care residency matches and representation

Aug 8, 2023

Study: Emergency department visits more likely for dementia patients with interprofessional primary care team

Nov 29, 2022

Students in health enrichment programs benefit from early team-based exposure

Oct 25, 2018

Health professionals work in teams: their training should prepare them

Jul 6, 2021

Study suggests interprofessional team training could prove effective in alcohol use disorder prevention and treatment

Mar 21, 2023

Recommended for you

Clinical trial assesses the efficacy of suvorexant in reducing delirium in older adults

6 hours ago

In-person contact linked with lower levels of loneliness in older adults

Aug 28, 2024

Low-dose THC reverses brain aging and enhances cognition in mice, research suggests

Aug 21, 2024

Marriage strongly associated with optimal health and well-being in men as they age

Study finds potential link between DNA markers and aging process

Aug 19, 2024

Cleaning up the aging brain: Scientists restore brain's waste removal system

Aug 15, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2024

A qualitative study identifying implementation strategies using the i-PARIHS framework to increase access to pre-exposure prophylaxis at federally qualified health centers in Mississippi

- Trisha Arnold ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3556-5717 1 , 2 ,

- Laura Whiteley 2 ,

- Kayla K. Giorlando 1 ,

- Andrew P. Barnett 1 , 2 ,

- Ariana M. Albanese 2 ,

- Avery Leigland 1 ,

- Courtney Sims-Gomillia 3 ,

- A. Rani Elwy 2 , 5 ,

- Precious Patrick Edet 3 ,

- Demetra M. Lewis 4 ,

- James B. Brock 4 &

- Larry K. Brown 1 , 2

Implementation Science Communications volume 5 , Article number: 92 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Mississippi (MS) experiences disproportionally high rates of new HIV infections and limited availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are poised to increase access to PrEP. However, little is known about the implementation strategies needed to successfully integrate PrEP services into FQHCs in MS.

The study had two objectives: identify barriers and facilitators to PrEP use and to develop tailored implementation strategies for FQHCs.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 19 staff and 17 PrEP-eligible patients in MS FQHCs between April 2021 and March 2022. The interview was guided by the integrated-Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework which covered PrEP facilitators and barriers. Interviews were coded according to the i-PARIHS domains of context, innovation, and recipients, followed by thematic analysis of these codes. Identified implementation strategies were presented to 9 FQHC staff for feedback.

Data suggested that PrEP use at FQHCs is influenced by patient and clinic staff knowledge with higher levels of knowledge reflecting more PrEP use. Perceived side effects are the most significant barrier to PrEP use for patients, but participants also identified several other barriers including low HIV risk perception and untrained providers. Despite these barriers, patients also expressed a strong motivation to protect themselves, their partners, and their communities from HIV. Implementation strategies included education and provider training which were perceived as acceptable and appropriate.

Conclusions

Though patients are motivated to increase protection against HIV, multiple barriers threaten uptake of PrEP within FQHCs in MS. Educating patients and providers, as well as training providers, are promising implementation strategies to overcome these barriers.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

We propose utilizing Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to increase pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among people living in Mississippi.

Little is currently known about how to distribute PrEP at FQHCs.

We comprehensively describe the barriers and facilitators to implementing PrEP at FQHCs.

Utilizing effective implementation strategies of PrEP, such as education and provider training at FQHCs, may increase PrEP use and decrease new HIV infections.

Introduction

The HIV outbreak in Mississippi (MS) is among the most critical in the United States (U.S.). It is distinguished by significant inequalities, a considerable prevalence of HIV in remote areas, and low levels of HIV medical care participation and virologic suppression [ 1 ]. MS has consistently ranked among the states with the highest HIV rates in the U.S. This includes being the 6th highest in new HIV diagnoses [ 2 ] and 2nd highest in HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men (MSM) compared to other states [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Throughout MS, the HIV epidemic disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minority groups, particularly among Black individuals. A spatial epidemiology and statistical modeling study completed in MS identified HIV hot spots in the MS Delta region, Southern MS, and in greater Jackson, including surrounding rural counties [ 5 ]. Black race and urban location were positively associated with HIV clusters. This disparity is often driven by the complex interplay of social, economic, and structural factors, including poverty, limited access to healthcare, and stigma [ 5 ].

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has gained significant recognition due to its safety and effectiveness in preventing HIV transmission when taken as prescribed [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. However, despite the progression in PrEP and its accessibility, its uptake has been slow among individuals at high risk of contracting HIV, particularly in Southern states such as MS [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. According to the CDC [ 5 ], “4,530 Mississippians at high risk for HIV could potentially benefit from PrEP, but only 927 were prescribed PrEP.” Several barriers hinder PrEP use in MS including limited access to healthcare, cost, stigma, and medical mistrust [ 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) are primary healthcare organizations that are community-based and patient-directed, serve geographically and demographically diverse patients with limited access to medical care, and provide care regardless of a patient’s ability to pay [ 18 ]. FQHCs in these areas exhibit reluctance in prescribing or counseling patients regarding PrEP, primarily because they lack the required training and expertise [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Physicians in academic medical centers are more likely to prescribe PrEP compared to those in community settings [ 22 ]. Furthermore, providers at FQHCs may exhibit less familiarity with conducting HIV risk assessments, express concerns regarding potential side effects of PrEP, and have mixed feelings about prescribing it [ 23 , 24 ]. Task shifting might also be needed as some FQHCs may lack sufficient physician support to manage all aspects of PrEP care. Tailored strategies and approaches are necessary for FQHCs to effectively navigate the many challenges that threaten their patients’ access to and utilization of PrEP.

The main objectives of this study were to identify the barriers and facilitators to PrEP use and to develop tailored implementation strategies for FQHCs providing PrEP. To service these objectives, this study had three specific aims. Aim 1 involved conducting a qualitative formative evaluation guided by the integrated-Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework- with FQHC staff and PrEP-eligible patients across three FQHCs in MS [ 25 ]. Interviews covered each of the three i-PARIHS domains: context, innovation, and recipients. These interviews sought to identify barriers and facilitators to implementing PrEP. Aim 2 involved using interview data to select and tailor implementation strategies from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project [ 26 ] (e.g., provider training) and methods (e.g., telemedicine, PrEP navigators) for the FQHCs. Aim 3 was to member-check the selected implementation strategies and further refine these if necessary. Data from all three aims are presented below. The standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR) checklist was used to improve the transparency of reporting this qualitative study [ 27 ].

Formative evaluation interviews

Interviews were conducted with 19 staff and 17 PrEP-eligible patients from three FQHCs in Jackson, Canton, and Clarksdale, Mississippi. Staff were eligible to participate if they were English-speaking and employed by their organization for at least a year. Eligibility criteria for patients included: 1) English speaking, 2) aged 18 years or older, 3) a present or prior patient at the FQHC, 4) HIV negative, and 5) currently taking PrEP or reported any one of the following factors that may indicate an increased risk for HIV: in the past year, having unprotected sex with more than one person with unknown (or positive) HIV status, testing positive for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) (syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia), or using injection drugs.

Data collection

The institutional review boards of the affiliated hospitals approved this study prior to data collection. An employee at each FQHC acted as a study contact and assisted with recruitment. The contacts advertised the study through word-of-mouth to coworkers and relayed the contact information of those interested to research staff. Patients were informed about the study from FQHC employees and flyers while visiting the FQHC for HIV testing. Those interested filled out consent-to-contact forms, which were securely and electronically sent to research staff. Potential participants were then contacted by a research assistant, screened for eligibility, electronically consented via DocuSign (a HIPAA-compliant signature capturing program), then scheduled for an interview. Interviews occurred remotely over Zoom, a HIPAA-compliant, video conferencing platform. Interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached. In addition to the interview, all participants were asked to complete a short demographics survey via REDCap, a HIPAA-compliant, online, data collection tool. Each participant received a $100 gift card for their time.

The i-PARIHS framework guided interview content and was used to create a semi-structured interview guide [ 28 ]. Within the i-PARIHS framework’s elements, the interview guide content included facilitators and barriers to PrEP use at the FQHC: 1) the innovation, (PrEP), such as its degree of fit with existing practices and values at FQHCs; 2) the recipients (individuals presenting to FQHCs), such as their PrEP awareness, barriers to receiving PrEP such as motivation, resources, support, and personal PrEP experiences; and 3) the context of the setting (FQHCs), such as clinic staff PrEP awareness, barriers providing PrEP services, and recommendations regarding PrEP care. Interviews specifically asked about the use of telemedicine, various methods for expanding PrEP knowledge for both patients and providers (e.g., social media, advertisements, community events/seminars), and location of services (e.g., mobile clinics, gyms, annual health checkups, health fairs). Staff and patients were asked the same interview questions. Data were reviewed and analyzed iteratively throughout data collection, and interview guides were adapted as needed.

Data analysis

Interviews were all audio-recorded, then transcribed by an outside, HIPAA-certified transcription company. Transcriptions were reviewed for accuracy by the research staff who conducted the interviews.

Seven members of the research team (TA, LW, KKG, AB, CSG, AL, LKB) independently coded the transcripts using an a priori coding schedule that was developed using the i-PARIHS and previous studies [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. All research team members were trained in qualitative methods prior to beginning the coding process. The coding scheme covered: patient PrEP awareness, clinic staff PrEP awareness, barriers to receiving PrEP services, barriers to providing PrEP services, and motivation to take PrEP. Each coder read each line of text and identified if any of the codes from the a priori coding framework were potentially at play in each piece of text. Double coding was permitted when applicable. New codes were created and defined when a piece of text from transcripts represented a new important idea. Codes were categorized according to alignment with i-PARIHS constructs. To ensure intercoder reliability, the first 50% of the interviews were coded by two researchers. Team meetings were regularly held to discuss coding discrepancies (to reach a consensus). Coded data were organized using NVivo software (Version 12). Data were deductively analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis, a six-step process for analyzing and reporting qualitative data, to determine themes relevant to selecting appropriate implementation strategies to increase PrEP use at FQHCs in MS [ 29 ]. The resulting thematic categories were used to select ERIC implementation strategies [ 26 ]. Elements for each strategy were then operationalized and the mechanism of change for each strategy was hypothesized [ 30 , 31 ]. Mechanisms define how an implementation strategy will have an effect [ 30 , 31 ]. We used the identified determinants to hypothesize the mechanism of change for each strategy.

Member checking focus groups

Member checking is when the data or results are presented back to the participants, who provide feedback [ 32 ] to check for accuracy [ 33 ] and improve the validity of the data [ 34 ]. This process helps reduce the possibility of misrepresentation of the data [ 35 ]. Member checking was completed with clinic staff rather than patients because the focus was on identifying strategies to implement PrEP in the FQHCs.

Two focus groups were conducted with nine staff from the three FQHCs in MS. Eligibility criteria were the same as above. A combination of previously interviewed staff and non-interviewed staff were recruited. Staff members were a mix of medical (e.g., nurses, patient navigators, social workers) and non-medical (e.g., administrative assistant, branding officer) personnel. Focus group one had six participants and focus group two had three participants. The goal was for focus group participants to comprise half of staff members who had previously been interviewed and half of non-interviewed staff.

Participants were recruited and compensated via the same methods as above. All participants electronically consented via DocuSign, and then were scheduled for a focus group. Focus groups occurred remotely over Zoom. Focus groups were conducted until data saturation was reached and no new information surfaced. The goal of the focus groups was to member-check results from the interviews and assess the feasibility and acceptability of selected implementation strategies. PowerPoint slides with the results and implementation strategies written in lay terms were shared with the participants, which is a suggested technique to use in member checking [ 33 ]. Participants were asked to provide feedback on each slide.

Focus groups were all audio-recorded, then transcribed. Transcriptions were reviewed for accuracy by the research staff who completed focus groups. Findings from the focus groups were synthesized using rapid qualitative analyses [ 36 , 37 ]. Facilitators (TA, PPE) both took notes during the focus groups of the primary findings. Notes were then compared during team meetings and results were finalized. Results obtained from previous findings of the interviews and i-PARIHS framework were presented. To ensure the reliability of results, an additional team member (KKG) read the transcripts to verify the primary findings and selected supportive quotes for each theme. Team meetings were regularly held to discuss the results.

Thirty-six semi-structured interviews in HIV hot spots were completed between April 2021 and March 2022. Among the 19 FQHC staff, most staff members had several years of experience working with those at risk for HIV. Staff members were a mix of medical (e.g., doctors, nurses, CNAs, social workers) and non-medical (e.g., receptionists, case managers) personnel. Table 1 provides the demographic characteristics for the 19 FQHC clinic staff and 17 FQHC patients.

Table 2 provides a detailed description of the findings within each category: PrEP knowledge, PrEP barriers, and PrEP motivation. Themes are described in detail, with representative quotes, below. Implementation determinants are specific factors that influence implementation outcomes and can be barriers or facilitators. Table 3 highlights which implementation determinants can increase ( +) or decrease (-) the implementation of PrEP at FQHCs in MS. Each determinant, mapped to its corresponding i-PARIHS construct, is discussed in more detail below. There were no significant differences in responses across the three FQHCs.

PrEP knowledge

Patient prep awareness (i-parihs: recipients).

Most patients had heard of PrEP and were somewhat familiar with the medication. One patient described her knowledge of PrEP as follows, “I know that PrEP is I guess a program that helps people who are high-risk with sexual behaviors and that doesn't have HIV, but they're at high-risk.”- Patient, Age 32, Female, Not on PrEP. However, many lacked knowledge of who may benefit from PrEP, where to receive a prescription, the different medications used for PrEP, and the efficacy of PrEP. Below is a comment made by a patient listing what she would need to know to consider taking PrEP. “I would need to know the price. I would need to know the side effects. I need to know the percentage, like, is it 100 or 90 percent effective.”— Patient, Age Unknown, Female, Not on PrEP. Patients reported learning about PrEP via television and social media commercials, medical providers, and their social networks. One patient reported learning about PrEP from her cousin. “The only person I heard it [PrEP] from was my cousin, and she talks about it all the time, givin’ us advice and lettin’ us know that it’s a good thing.”— Patient, Age Unknown, Female, Not on PrEP.

Clinic Staff PrEP Awareness (i-PARIHS: Context)

Training in who may benefit from PrEP and how to prescribe PrEP varied among clinic staff at different FQHCs. Not all clinics offered formal PrEP education for employees; however, most knew that PrEP is a tool used for HIV prevention. Staff reported learning about PrEP via different speakers and meetings. A clinic staff member reported learning about PrEP during quarterly meetings. “Well, sometimes when we have different staff meetings, we have them quarterly, and we discuss PrEP. Throughout those meetings, they tell us a little bit of information about it, so that's how I know about PrEP.” – Staff, Dental Assistant, Female. Some FQHC staff members reported having very little knowledge of PrEP. One staff member shared that she knew only the “bare minimum” about PrEP, stating,

“I probably know the bare minimum about PrEP. I know a little about it [PrEP] as far as if taken the correct way, it can prevent you from gettin’ HIV. I know it [PrEP] doesn’t prevent against STDs but I know it’s a prevention method for HIV and just a healthier lifestyle.” –Staff, Accountant, Female

A few of the organizations had PrEP navigators to which providers refer patients. These providers were well informed on who to screen for PrEP eligibility and the process for helping the patient obtain a PrEP prescription. One clinic staff member highlighted how providers must be willing to be trained in the process of prescribing PrEP and make time for patients who may benefit. Specifically, she said,

“I have been trained [for PrEP/HIV care]. It just depends on if that’s something that you’re willing to do, they can train on what labs and stuff to order ’cause it’s a whole lot of labs. But usually, I try to do it. At least for everybody that’s high-risk.” – Staff, OB/GYN Nurse Practitioner, Female

Another clinic staff member reported learning about PrEP while observing another staff member being training in PrEP procedures.

“Well, they kinda explained to me what it [PrEP] is, but I was in training with the actual PrEP person, so it was kinda more so for his training. I know what PrEP is. I know the medications and I know he does a patient assistance program. If my patients have partners who are not HIV positive and wanna continue to be HIV negative, I can refer 'em.” – Staff, Administrative Assistant, Female

PrEP barriers

Barriers receiving prep services (i-parihs: recipients, innovation).

Several barriers to receiving PrEP services were identified in both patient and clinic staff interviews. There was a strong concern for the side effects of PrEP. One patient heard that PrEP could cause weight gain and nightmares, “I’m afraid of gaining weight. I’ve heard that actual HIV medication, a lotta people have nightmares or bad dreams.” - Patient, Age 30, Female, Not on PrEP. Another patient was concerned about perceived general side effects that many medications have. “Probably just the [potential] side effects. You know, most of the pills have allergic reactions and side effects, dizziness, seizures, you know.” - Patient, Age 30, Female, Not on PrEP.

The burden of remembering to take a daily pill was also mentioned as a barrier to PrEP use. One female patient explained how PrEP is something she is interested in taking; however, she would be unable to take a daily medication.

“I’m in school now and not used to takin’ a medication every day. I was takin’ a birth control pill, but now take a shot. That was one of the main reasons that I didn’t start PrEP cause they did tell me I could get it that day. So like I wanna be in the mind state to where I’m able to mentally, in my head, take a pill every day. PrEP is somethin’ that I wanna do.” - Patient, Age Unknown, Female, Not on PrEP

Stigma and confidentiality were also barriers to PrEP use at FQHCs. One staff member highlighted how in small communities it is difficult to go to a clinic where employees know you personally. Saying,

“If somebody knows you’re going to talk to this specific person, they know what you’re goin’ back there for, and that could cause you to be a little hesitant in coming. So there’s always gonna be a little hesitancy or mistrust, especially in a small community. Everybody knows everybody. The people that you’re gonna see goes to church with you.” – Staff, Accountant, Female

Some patients had a low perceived risk of HIV and felt PrEP may be an unnecessary addition to their routine. One patient shared that if she perceived she was at risk for HIV, then she would be more interested in taking PrEP, “If it ever came up to the point where I would need it [PrEP], then yes, I would want to know more about it [PrEP].”— Patient, Age Unknown, Female, Not on PrEP.

Some participants expressed difficulty initiating or staying on PrEP because of associated costs, transportation and/or scheduling barriers. A staff member explained how transportation may be available in the city but not available in more rural areas,

“I guess it all depends on the person and where they are. In a city it might take a while, but at least they have the transportation compared to someone that lives in a rural area where transportation might be an issue.” - Staff, Director of Nurses, Female

Childcare during appointments was also mentioned as a barrier, “It looks like here a lot of people don't have transportation or reliable transportation and another thing I don't have anybody to watch my kids right now. —Staff, Patient Navigator, Female.

Barriers Providing PrEP Services (i-PARIHS: Context)

Barriers to providing PrEP services were also identified. Many providers are still not trained in PrEP procedures nor feel comfortable discussing or prescribing PrEP to their patients. One patient shared an experience of going to a provider who was PrEP-uninformed and assumed his medication was to treat HIV,

“Once I told her about it [PrEP], she [clinic provider] literally right in front of me, Googled it [PrEP], and then she was Googlin’ the medication, Descovy. I went to get a lab work, and she came back and was like, “Is this for treatment?” I was like, “Why would you automatically think it’s for treatment?” I literally told her and the nurse, “I would never come here if I lived here.” - Patient, Age 50, Male, Taking PrEP

Also, it was reported that there is not enough variety in the kind of providers who offer PrEP (e.g., OB/GYN, primary care). Many providers such as OB/GYNs could serve as a great way to reach individuals who may benefit from PrEP; however, patients reported a lack of PrEP being discussed in annual visits. “My previous ones (OB/GYN), they’ve talked about birth control and every other method and they asked me if I wanted to get tested for HIV and any STIs, but the conversation never came up about PrEP.” -Patient, Age Unknown, Female, Not on PrEP.

PrEP motivation

Motivation to take prep (i-parihs: recipients).

Participants mentioned several motivators that enhanced patient willingness to use PrEP. Many patients reported being motivated to use PrEP to protect themselves and their partners from HIV. Additionally, participants reported wanting to take PrEP to help their community. One patient reported being motivated by both his sexuality and the rates of HIV in his area, saying, “I mean, I'm bisexual. So, you know, anyway I can protect myself. You know, it's just bein' that the HIV number has risen. You know, that's scary. So just being, in, an area with higher incidents of cases.”— Patient, Age Unknown, Male, Not on PrEP . Some participants reported that experiencing an HIV scare also motivated them to consider using PrEP. One patient acknowledged his behaviors that put him at risk and indicated that this increased his willingness to take PrEP, “I was havin' a problem with, you know, uh, bein' promiscuous. You know? So it [PrEP] was, uh, something that I would think, would help me, if I wasn't gonna change the way I was, uh, actin' sexually.”— Patient, Age Unknown, Male, Taking PrEP .

Table 3 outlines the implementation strategies identified from themes from the interview and focus group data. Below we recognize the barriers and determinants to PrEP uptake for patients attending FQHCs in MS by each i-PARIHS construct (innovation, recipient, context) [ 28 ]. Based on the data, we mapped the determinants to specific strategies from the ERIC project [ 26 ] and hypothesized the mechanism of change for each strategy [ 30 , 31 ].

Two focus groups were conducted with nine staff from threeFQHCs in MS. There were six participants in the 1st focus group and three in the 2nd. Staff members were a mix of medical (e.g., nurses, patient navigators, social workers) and non-medical (e.g., administrative assistant, branding officer) personnel. Table 4 provides the demographic characteristics for the FQHC focus group participants.

Staff participating in the focus groups generally agreed that the strategies identified via the interviews were appropriate and acceptable. Focus group content helped to further clarify some of the selected strategies. Below we highlight findings by each strategy domain.

PrEP information dissemination

Participants specified that awareness of HIV is lower, and stigma related to PrEP is higher in rural areas. One participant specifically said,

“There is some awareness but needs to be more awareness, especially to rural areas here in Mississippi. If you live in the major metropolitan areas there is a lot of information but when we start looking at the rural communities, there is not a lot.” – Staff, Branding Officer, Male

Participants strongly agreed that many patients don’t realize they may benefit from PrEP and that more inclusive advertisements are needed. A nurse specifically stated,

“ When we have new clients that come in that we are trying to inform them about PrEP and I have asked them if they may have seen the commercial, especially the younger population. They will say exactly what you said, that “Oh, I thought that was for homosexuals or whatever,” and I am saying “No, it is for anyone that is at risk.” – Staff, Nurse, Female

Further, staff agreed that younger populations should be included in PrEP efforts to alleviate stigma. Participants added that including PrEP information with other prevention methods (i.e., birth control, vaccines) is a good place to include parents and adolescents:

“Just trying to educate them about Hepatitis and things of that nature, Herpes. I think we should also, as they are approaching 15, the same way we educate them about their cycle coming on and what to expect, it’s almost like we need to start incorporating this (PrEP education), even with different forms of birth control methods with our young ladies.” – Staff, Nurse, Female

Participants agreed that PrEP testimonials would be helpful, specifically from people who started PrEP, stopped, and then were diagnosed with HIV. Participants indicated that this may improve PrEP uptake and persistence. One nurse stated:

“I have seen where a patient has been on PrEP a time or two and at some point, early in the year or later part of the year, and we have seen where they’ve missed those appointments and were not consistent with their medication regimen. And we have seen those who’ve tested positive for HIV. So, if there is a way we could get one of those patients who will be willing to share their testimony, I think they can really be impactful because it’s showing that taking up preventive measures was good and then kind of being inconsistent, this is what the outcome is, unfortunately.” – Staff, Nurse, Female

Increase variety and number of PrEP providers

Participants agreed that a “PrEP champion” (someone to promote PrEP and answer PrEP related questions) would be helpful, especially for providers who need more education about PrEP to feel comfortable prescribing. A patient navigator said,