Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

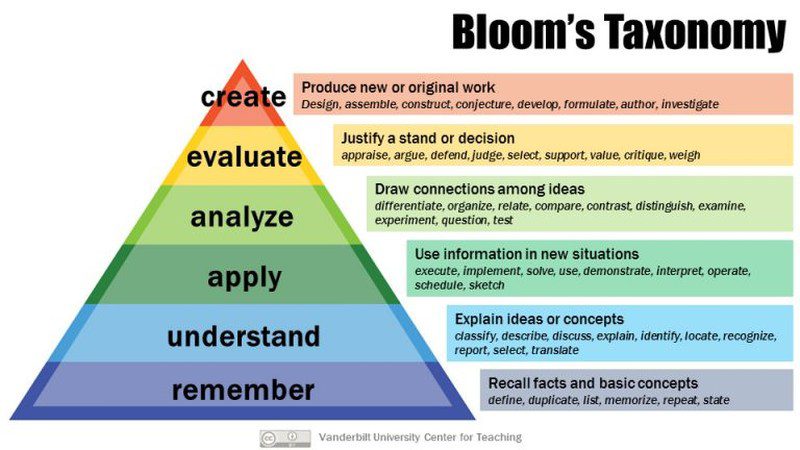

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Multiple Perspectives: Building Critical Thinking Skills

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

This lesson develops students' critical thinking skills through reading and interacting with multiple-perspectives texts. Students analyze selected texts, using metacognitive strategies such as visualizing, synthesizing, and making connections, to learn about multiple points of view. By studying Doreen Cronin's Diary of a Spider/ Worm/ Fly books, students develop a model for an original diary based on an animal of their choosing. Students conduct online research on their chosen animal and use the information gathered to create several diary entries from the perspective of that animal. Students' completed diaries are shared with the class and the larger school community.

Featured Resources

- Fish Is Fish : This Leo Lionni book encourages students to use their skills in thinking from different perspectives.

- Fish Is Fish Script: The script, written by the lesson author, contains original text from the book as well as some new additional text.

- Doreen Cronin as Our Mentor: This printout summarizes the types of entries Doreen Cronin uses in her Diary of a Spider/Worm/Fly books and provides students with ideas and starting points for their own diary entries.

- Websites for Research: A list of excellent, easy-to-navigate student-oriented websites that provide facts on all types of animals.

From Theory to Practice

- As a result of state standards that require students to engage in critical and analytical thinking related to texts, teachers have been turning toward the notion of critical literacy to address such requirements. Though it is an educational buzz word, there is no clear definition of critical literacy, which creates difficulties for teachers who attempt to incorporate deep, critical thinking into their instruction but do not get much guidance from state standards as to how to design instruction.

- Clarke and Whitney provide a three-part framework for incorporating critical literacy into the classroom: (1) Students start by digging beyond the surface of a text, deconstructing it, and then analyzing and interrogating the layers of meaning; (2) students take what they have learned from analyzing the text to reconstruct it and create new ways of thinking; and (3) by taking what they have learned from deconstructing and reconstructing the text, the students can connect to the larger world and even take social action.

- Multiple-perspective books, which intentionally emphasize different viewpoints, help students develop critical thinking skills and learn how to see beyond their own lives to the world outside. Such books, coupled with Clarke and Whitney’s framework, help students to understand, visualize, and empathize with someone else’s struggles.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

- Computers with Internet access (one computer per student, if possible)

- Pencils, crayons, markers, colored pencils, erasers

- Construction paper for cover of diary (one piece for each student or student pair)

- Seven Blind Mice by Ed Young (Philomel, 1992)

- Fish Is Fish by Leo Lionni (Random House, 1998)

- Diary of a Worm by Doreen Cronin (HarperCollins, 2003)

- Diary of a Spider by Doreen Cronin (HarperCollins, 2005)

- Diary of a Fly by Doreen Cronin (HarperCollins, 2007)

- Assorted Zoobooks or Ranger Rick magazines

- Baseball caps labeled Fish and Frog (optional)

- Fish Is Fish Script

- Diary Entry Template

- Doreen Cronin as Our Mentor

- Diary Planning Sheet

- Research Notes

- Can I See Different Perspectives?

- Partnership Reflection Form

- Self-Assessment: What Did I Learn?

- Sketch to Stretch

- Fish Is Fish Venn Diagram

- Websites for Research

- Teacher Rubric: Student Diary Entries

- Teacher Rating Form: Sketch to Stretch

- Teacher Rubric: Fish Is Fish

- Red-Eyed Tree Frog

Preparation

- Print out several copies of the Red-Eyed Tree Frog photograph (enough for a small group of students to share) and cut each photograph into several pieces.

- Make one copy for each student of Sketch to Stretch , Can I See Different Perspectives? , Fish Is Fish Script , Fish Is Fish Venn Diagram , Doreen Cronin as Our Mentor , Diary Planning Sheet , Research Notes , and Self-Assessment: What Did I Learn?

- Make three copies for each student of the Partnership Reflection Form .

- Make five copies for each student of the Diary Entry Template .

- Bookmark Websites for Research on classroom computers or bookmark each of the websites on the list.

- Print one copy each of the Teacher Rubric: Student Diary Entries , Teacher Rating Form: Sketch to Stretch and Teacher Rubric: Fish Is Fish .

- Obtain one copy of Seven Blind Mice by Ed Young and practice reading aloud.

- Obtain one copy of Fish Is Fish by Leo Lionni for teacher reference.

- Obtain multiple copies of Diary of a Worm , Diary of a Spider , and Diary of a Fly by Doreen Cronin.

- Obtain an assortment of Zoobooks and or Ranger Rick magazines for initial research.

- Reserve time in the computer lab for Session 5, if necessary.

- Familiarize yourself with all of the Websites for Research so you can assist students in navigating and searching these sites.

- If desired, have students bring in baseball caps prior to Session 3 and label each cap with either Fish or Frog . Each student needs a baseball cap, and because students will be working in partners, one student will receive the “Fish” label and the other student will receive the “Frog” label.

Student Objectives

Students will

- Develop a basic understanding of narrative perspective

- Become aware of the presence—and the value—of including different voices in a text; and understand how presenting an issue from various vantage points adds multiple layers of meaning

- Practice research skills by using both print and online sources

- Organize and synthesize facts from research

- Use critical literacy skills to view life from the perspective of a selected animal

- Practice writing factual information from a specific point of view, in a diary format

- Develop teamwork skills through working with a partner and sharing the responsibilities of research, planning, writing, and creating the final diary from the chosen animal’s perspective

Session 1: An Introduction to Multiple Perspectives

- To begin the exploration of perspective, explain to students that you are going to give them a small piece of a larger picture, which has been cut into pieces.

- Model how to create a picture based on a small part of the photograph.

- Organize students into small groups of 3–4 students. After groups have been formed, distribute pieces of the photograph to the members of each group. Have students draw what they think the rest of the photo might look like, without looking at the other pieces. (Remind them to focus on their part only.)

- Have the members of each group share their illustrations with one another. Engage students in discussion about the similarities and differences of their illustrations. Ask them to predict what the entire picture might be.

- Assemble all of the pieces of the picture to reveal the entire image.

- Connect to photograph activity, where each student formed a different idea of the original photograph because each was seeing it from a different perspective.

- Point out that there are always at least two sides to every story, which is why people go to court and why teachers ask each student involved in a disagreement to tell his or her side of a story.

- Explain that we come to understand a character’s perspective by creating mental images.

- When we pay attention to a character’s perspective (or all of the characters’ perspectives), we are engaging in critical thinking , and this kind of thinking helps us be better readers.

- Sum up the explanation of perspective with the analogy of “walking in someone else’s shoes.” In the case of reading, you are taking off your own shoes and putting on the narrator’s shoes to walk through the story.

Session 2: <em>Seven Blind Mice</em>

- Introduce the book Seven Blind Mice by telling students that it shows the perspective of seven different characters. Explain that they will first take apart (deconstruct) the story and sketch it from each character’s perspective and then put together all of their images and see if they can get an idea of the entire picture.

- Distribute a copy of the Sketch to Stretch sheet to each student and explain that each block is to be used to depict the perspective of one of the mice in the story.

- Activate students’ schema by having them briefly discuss how a mouse’s perspective is different from a human’s. Before reading, have students pretend to take off their shoes and imagine that they are putting on a mouse’s shoes.

- Read aloud Seven Blind Mice . Stop after each mouse’s description of the object ( pillar , snake , spear , cliff , fan , rope ) and have students complete a box on their Sketch to Stretch sheet.

- Before reading the ending of the book, have the students try to put together the images from the different perspectives to infer what the entire picture might be. After this discussion, finish the book.

- To close the lesson, have the students complete the self-assessment form Can I See Different Perspectives?

Session 3: Walking in a Character’s Shoes

- Introduce the book Fish Is Fish and ask students to predict what the book might be about. Also encourage them to ask questions about the book and think about what kinds of pictures they might see in the book. Encourage students to explain their thoughts as they discuss.

- Review the idea of perspective and connect it to Fish Is Fish . Ask students whose perspective they think Fish Is Fish will be told from and why. Then explain to the students that Fish Is Fish is told from the very different perspectives of a fish and of a tadpole that turns into a frog.

- Create student partnerships (2 students—if an odd number of students, one group of 3 and modify the activities as necessary). Students will complete the remaining sessions and activities with this partner.

- Distribute copies of the Fish Is Fish Venn Diagram and explain how students will fill in the characteristics of Fish and Tadpole/Frog in the appropriate spaces as they read.

- Distribute copies of the Fish Is Fish Script . The students will verbally read aloud the script with their partners. Note to students that whoever reads Fish’s part also must read as Narrator 1 and the partner who reads Frog’s part must also read Narrator 2. Provide students with the appropriate labels for their baseball caps (optional).

- Circulate and observe as students read through script with their partners.

- When students have read through about half of the script (about the halfway mark where Fish and Frog say good night), ask them to stop and jot down their thoughts about each character’s perspective. After they finish the book, they will complete the Fish Is Fish Venn Diagram and discuss as a pair.

- Have students discuss in their pairs which character (Fish or Frog) had a more positive perspective of life and why. Then, share thoughts as a class.

- To close the lesson, ask students whether playing the part of the fish and the frog after learning about perspective helped them feel as though they were thinking like the fish or frog.

Session 4: Using an Author as a Mentor

- Tell students that during the next two lessons they will complete a project using their skills of thinking from the perspective of someone or something else.

- Introduce Diary of a Spider , Diary of a Worm , and Diary of a Fly , and ask students how the books are similar. (Make sure students’ response is that they are all the diary of something.) Also ask students to predict what kind of project they think they will be working on (creating a diary from the perspective of an insect/animal).

- Tell students that they will be writing a diary from the perspective of an animal of their choosing. Students will be working with the partners they read with during the last session to create this diary. At this time, students can just begin to think about which animal they would like to “become.” A final decision does not need to be made at this point in time.

- Ask students how they think they could learn about the perspective of a particular animal (researching, asking questions, reading about the animal).

- Tell students that similarities among an author’s books can be used to form a “recipe” for another story. Distribute one copy of each book to each set of partners. If there aren’t enough copies, give each partnership one book and allow students to skim for about three minutes and then rotate with another group. After students have looked through the books, ask students what similarities they notice among the Diary of a Spider/Worm/Fly books. What is similar in the story lines? The entries?

- Distribute copies of Doreen Cronin as Our Mentor . Read through the list of “ingredients,” and have each student identify at least four entries they would like to emulate in their diary. You may want to require that all diaries follow Cronin’s formulas for beginning and ending but that the fifth entry of each student will be either the beginning or the ending. Encourage students to use different diary entry ideas within their pairs and to choose different items to emulate, as they will be writing the diary together.

- Distribute a copy of the Research Notes worksheet to each student, and have students go over the different types of facts they should look for about the animal.

- Provide students with time to discuss with their partners what animal they will research. You may want to go through your magazines ahead of time so you know which animals you have information for. Different partnerships may choose the same animal as long as information sources are available for each partnership.

- Bring students back together for short whole-class instruction. Model how to form additional questions students will need to answer to complete their animal diaries. For example, for a diary entry about the animal at school, you might think aloud, “Hmmm, we learn things in school. What might this animal need to learn when it is young or at some point during its lifetime?” For a diary entry about a nightmare the animal might have, you could think aloud: “Well, when I have nightmares they are always about something I am afraid of, so what might this animal be afraid of—afraid enough to have a nightmare?”

- Guide students to begin skimming through the Zoobooks or Ranger Rick magazines to gather some information about animals. Quickly review how the headings on each page can guide the reader to particular information.

- To close the session, have two sets of partners meet and share information about what they have found.

Session 5: Gathering the Ingredients

- When we read a story we see it from the perspective, or point of view, of the narrator, who may also be a character in the story.

- Different characters in the story have different perspectives on the events.

- Awareness of different perspectives is a type of critical thinking.

- Remind students that they will be working to write a diary from the perspective of a chosen animal. If necessary, review research and note-taking techniques.

- Have students review the preliminary research they conducted with Zoobooks or Ranger Rick magazines during the last lesson, and formulate some additional questions they would like to answer through their research.

- In the computer lab or on classroom computers, have students open the Websites for Research . Explain that students should use these sites to find information about their chosen animals and answer as many questions as possible on the Research Notes worksheet. Assist students in navigating the sites and finding the needed information. Partners can work together to gather the information, or each partner can work separately and compare and combine information in the end.

Session 6: Planning for the Diary

- Have students review their Research Notes from the previous session and select interesting facts to include in their animal diaries.

- Decides who will write the opening entry and who will write the closing entry

- Decides on dates for entries 1–10 ahead of time so that the entries are in consecutive order when written and then combined to form the diary

- As students finish planning, provide each student with five copies of the Diary Entry Template . Students can begin working on their entries today and complete them in Sessions 7 and 8.

Sessions 7 and 8: Writing From a Different Perspective

- If not distributed during the last session, provide each student with five copies of the Diary Entry Template . Allow students 30–40 minutes to work on constructing journal entries from their animal’s perspective. Encourage them to use their skills in thinking from another’s perspective while creating journal entries. Guide and assist students as needed while they create their journal entries.

- After students have written all of their entries, they should illustrate the various entries.

- Have students create a diary cover including the title ( Diary of a ______) and the name(s) of the author(s). Assist students in assembling their diaries, alternating pages by student.

Session 9: Sharing Our Learning

Set aside a class session for partner sets to share their diaries with the class orally. Since students worked in pairs, photocopy the diaries so that each partner has a copy. After sharing, make sure to distribute Self-Assessment: What Did I Learn? form for each student to complete independently.

- Have students use Microsoft PowerPoint or Smart Notebook software to create a digital version of their diaries. Assist them in adding a soundtrack of themselves reading the diary aloud if desired. Upload to the school website to share with students’ families, other classes, and the community.

- Have students visit younger classes and share their diaries as read-alouds or in a Readers Theatre format.

- To continue their study of multiple perspectives, have students read The Big Orange Splot by Daniel Pinkwater and rewrite the text as a script for Readers Theatre.

- Have students shadow another person—mother, father, teacher, sibling, or even a pet—for several days, taking notes and, if possible, interviewing the subject. Students could then write a diary from the perspective of the person they “shadowed,” using Doreen Cronin’s entries as models.

- Students can use Fish Is Fish Script for a Readers Theatre performance.

- Students can visit the Diary of a Fly website to remind them of their project and connect their learning to technology.

Student Assessment / Reflections

- At the end of Session 1, have students assess their ability to understand characters’ perspectives using the self assessment Can I See Different Perspectives?

- Use the Teacher Rating Form: Sketch to Stretch to reflect upon the students’ success with the Sketch to Stretch activity in Session 2.

- Use the Teacher Rubric: Fish Is Fish to assess students’ success with using critical thinking skills to think from different perspectives.

- Observe as the students discuss the similarities between Doreen Cronin’s books, as well as the entries they are interested in. Are students noticing similarities? Are they focusing on a particular subject that they find interesting?

- Observe students as they formulate additional questions for research. Are their questions appropriate for finding the information needed for their diary entries? Are students formulating questions with ease or do they require assistance in formulating questions?

- Observe students as they engage in research on the web. Are students locating information with ease? Are they using their worksheets to record and organize information?

- Assess students’ writing, research, and critical thinking skills through the use of the Teacher Rubric: Student Diary Entries .

- Students will reflect on their work by completing an end-of-unit Self-Assessment: What Did I Learn?

- Lesson Plans

- Student Interactives

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

The Will to Teach

Critical Thinking in the Classroom: A Guide for Teachers

In the ever-evolving landscape of education, teaching students the skill of critical thinking has become a priority. This powerful tool empowers students to evaluate information, make reasoned judgments, and approach problems from a fresh perspective. In this article, we’ll explore the significance of critical thinking and provide effective strategies to nurture this skill in your students.

Why is Fostering Critical Thinking Important?

Strategies to cultivate critical thinking, real-world example, concluding thoughts.

Critical thinking is a key skill that goes far beyond the four walls of a classroom. It equips students to better understand and interact with the world around them. Here are some reasons why fostering critical thinking is important:

- Making Informed Decisions: Critical thinking enables students to evaluate the pros and cons of a situation, helping them make informed and rational decisions.

- Developing Analytical Skills: Critical thinking involves analyzing information from different angles, which enhances analytical skills.

- Promoting Independence: Critical thinking fosters independence by encouraging students to form their own opinions based on their analysis, rather than relying on others.

Creating an environment that encourages critical thinking can be accomplished in various ways. Here are some effective strategies:

- Socratic Questioning: This method involves asking thought-provoking questions that encourage students to think deeply about a topic. For example, instead of asking, “What is the capital of France?” you might ask, “Why do you think Paris became the capital of France?”

- Debates and Discussions: Debates and open-ended discussions allow students to explore different viewpoints and challenge their own beliefs. For example, a debate on a current event can engage students in critical analysis of the situation.

- Teaching Metacognition: Teaching students to think about their own thinking can enhance their critical thinking skills. This can be achieved through activities such as reflective writing or journaling.

- Problem-Solving Activities: As with developing problem-solving skills , activities that require students to find solutions to complex problems can also foster critical thinking.

As a school leader, I’ve seen the transformative power of critical thinking. During a school competition, I observed a team of students tasked with proposing a solution to reduce our school’s environmental impact. Instead of jumping to obvious solutions, they critically evaluated multiple options, considering the feasibility, cost, and potential impact of each. They ultimately proposed a comprehensive plan that involved water conservation, waste reduction, and energy efficiency measures. This demonstrated their ability to critically analyze a problem and develop an effective solution.

Critical thinking is an essential skill for students in the 21st century. It equips them to understand and navigate the world in a thoughtful and informed manner. As a teacher, incorporating strategies to foster critical thinking in your classroom can make a lasting impact on your students’ educational journey and life beyond school.

1. What is critical thinking? Critical thinking is the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment.

2. Why is critical thinking important for students? Critical thinking helps students make informed decisions, develop analytical skills, and promotes independence.

3. What are some strategies to cultivate critical thinking in students? Strategies can include Socratic questioning, debates and discussions, teaching metacognition, and problem-solving activities.

4. How can I assess my students’ critical thinking skills? You can assess critical thinking skills through essays, presentations, discussions, and problem-solving tasks that require thoughtful analysis.

5. Can critical thinking be taught? Yes, critical thinking can be taught and nurtured through specific teaching strategies and a supportive learning environment.

Related Posts

7 simple strategies for strong student-teacher relationships.

Getting to know your students on a personal level is the first step towards building strong relationships. Show genuine interest in their lives outside the classroom.

Connecting Learning to Real-World Contexts: Strategies for Teachers

When students see the relevance of their classroom lessons to their everyday lives, they are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and retain information.

Encouraging Active Involvement in Learning: Strategies for Teachers

Active learning benefits students by improving retention of information, enhancing critical thinking skills, and encouraging a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Collaborative and Cooperative Learning: A Guide for Teachers

These methods encourage students to work together, share ideas, and actively participate in their education.

Experiential Teaching: Role-Play and Simulations in Teaching

These interactive techniques allow students to immerse themselves in practical, real-world scenarios, thereby deepening their understanding and retention of key concepts.

Project-Based Learning Activities: A Guide for Teachers

Project-Based Learning is a student-centered pedagogy that involves a dynamic approach to teaching, where students explore real-world problems or challenges.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Français

- Preparatory

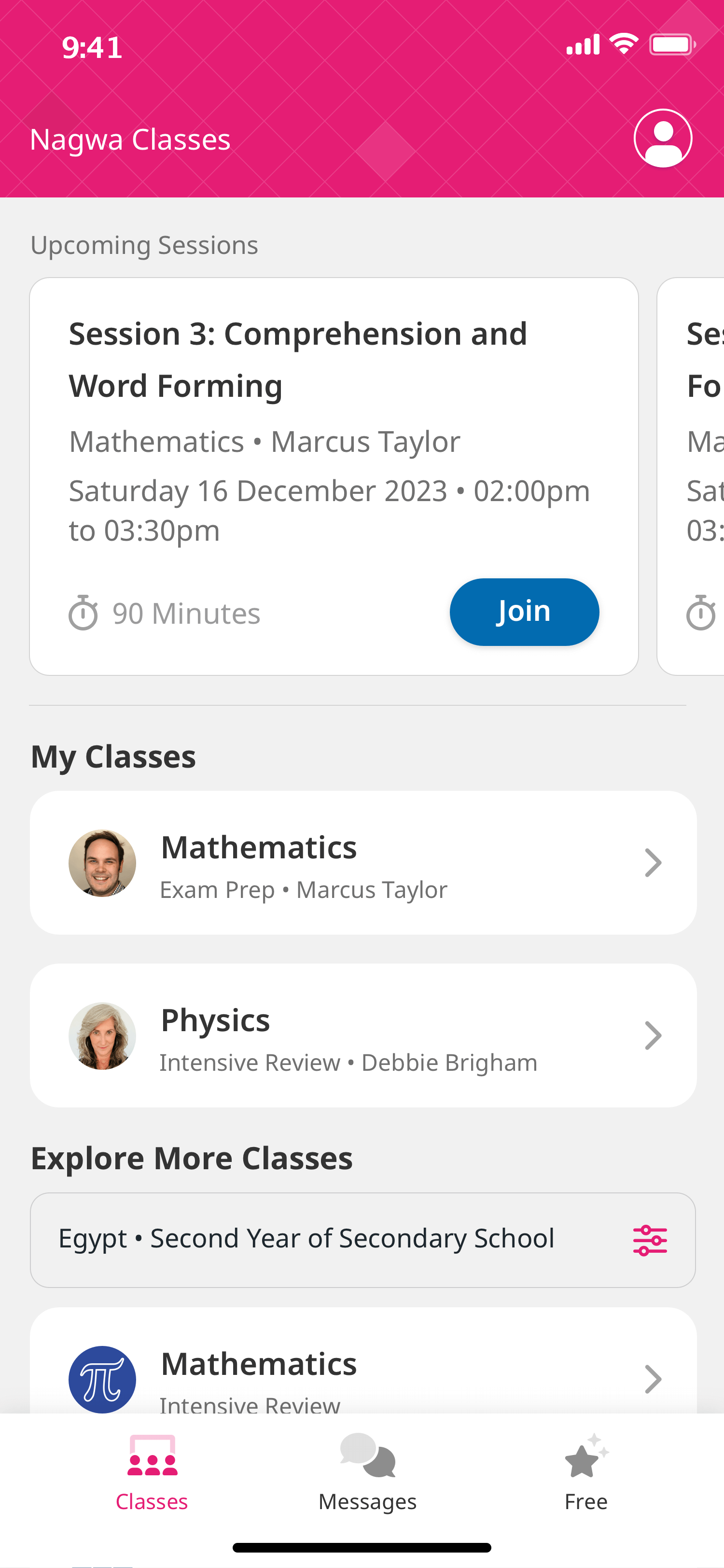

Lesson Plan: Critical Thinking: Definitions, Skills, and Examples

This lesson plan includes the objectives of the lesson teaching students how to define critical thinking and identify and employ some critical thinking skills.

Students will be able to

- understand the definition of critical thinking,

- identify five components of critical thinking,

- identify and employ critical thinking skills,

- identify and apply four steps of critical thinking.

Join Nagwa Classes

Attend live sessions on Nagwa Classes to boost your learning with guidance and advice from an expert teacher!

- Interactive Sessions

- Chat & Messaging

- Realistic Exam Questions

Nagwa uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Learn more about our Privacy Policy

Want a daily email of lesson plans that span all subjects and age groups?

Subjects all subjects all subjects the arts all the arts visual arts performing arts value of the arts back business & economics all business & economics global economics macroeconomics microeconomics personal finance business back design, engineering & technology all design, engineering & technology design engineering technology back health all health growth & development medical conditions consumer health public health nutrition physical fitness emotional health sex education back literature & language all literature & language literature linguistics writing/composition speaking back mathematics all mathematics algebra data analysis & probability geometry measurement numbers & operations back philosophy & religion all philosophy & religion philosophy religion back psychology all psychology history, approaches and methods biological bases of behavior consciousness, sensation and perception cognition and learning motivation and emotion developmental psychology personality psychological disorders and treatment social psychology back science & technology all science & technology earth and space science life sciences physical science environmental science nature of science back social studies all social studies anthropology area studies civics geography history media and journalism sociology back teaching & education all teaching & education education leadership education policy structure and function of schools teaching strategies back thinking & learning all thinking & learning attention and engagement memory critical thinking problem solving creativity collaboration information literacy organization and time management back, filter by none.

- Elementary/Primary

- Middle School/Lower Secondary

- High School/Upper Secondary

- College/University

- TED-Ed Animations

- TED Talk Lessons

- TED-Ed Best of Web

- Under 3 minutes

- Under 6 minutes

- Under 9 minutes

- Under 12 minutes

- Under 18 minutes

- Over 18 minutes

- Algerian Arabic

- Azerbaijani

- Cantonese (Hong Kong)

- Chinese (Hong Kong)

- Chinese (Singapore)

- Chinese (Taiwan)

- Chinese Simplified

- Chinese Traditional

- Chinese Traditional (Taiwan)

- Dutch (Belgium)

- Dutch (Netherlands)

- French (Canada)

- French (France)

- French (Switzerland)

- Kurdish (Central)

- Luxembourgish

- Persian (Afghanistan)

- Persian (Iran)

- Portuguese (Brazil)

- Portuguese (Portugal)

- Spanish (Argentina)

- Spanish (Latin America)

- Spanish (Mexico)

- Spanish (Spain)

- Spanish (United States)

- Western Frisian

sort by none

- Longest video

- Shortest video

- Most video views

- Least video views

- Most questions answered

- Least questions answered

What happens when nature goes viral?

Lesson duration 05:15

1,687,392 Views

How to be confident

Lesson duration 05:03

3,417,343 Views

Why we should draw more (and photograph less)

Lesson duration 02:53

382,784 Views

How well do masks work?

Lesson duration 08:21

2,148,990 Views

Am I Really A Visual Learner?

Lesson duration 02:38

301,021 Views

Why you don’t hear about the ozone layer anymore

Lesson duration 08:35

9,240,252 Views

Why don't we throw trash in volcanoes?

Lesson duration 03:04

1,826,695 Views

The coronavirus explained and how you can combat it

88,850,685 Views

Why some people don't have an inner monologue

Lesson duration 12:03

2,911,771 Views

How to design climate-resilient buildings - Alyssa-Amor Gibbons

Lesson duration 14:12

46,359 Views

Where do your online returns go? - Aparna Mehta

Lesson duration 07:39

83,535 Views

Can you outsmart the fallacy that divided a nation?

Lesson duration 04:42

728,368 Views

How do you know what's true?

Lesson duration 05:12

1,278,305 Views

How much electricity does it take to power the world?

Lesson duration 05:02

415,697 Views

The material that could change the world... for a third time

Lesson duration 05:27

969,970 Views

This thought experiment will help you understand quantum mechanics

Lesson duration 04:59

303,293 Views

Can you solve the monster duel riddle?

Lesson duration 05:36

3,521,553 Views

Can you outsmart a troll (by thinking like one)?

Lesson duration 05:01

770,257 Views

Can you solve the riddle and escape Hades?

Lesson duration 05:00

2,835,449 Views

The World Machine | Think Like A Coder, Ep 10

Lesson duration 12:10

353,787 Views

"Other": A brief history of American xenophobia

Lesson duration 07:11

60,399 Views

How to fix a broken heart - Guy Winch

Lesson duration 12:26

10,729,837 Views

Can you solve the sorting hat riddle?

Lesson duration 06:00

2,841,359 Views

How to outsmart the Prisoner’s Dilemma

Lesson duration 05:45

4,613,449 Views

- Our Mission

A Critical Thinking Framework for Elementary Students

Guiding young students to engage in critical thinking fosters their ability to create and engage with knowledge.

Critical thinking is using analysis and evaluation to make a judgment. Analysis, evaluation, and judgment are not discrete skills; rather, they emerge from the accumulation of knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge does not mean students sit at desks mindlessly reciting memorized information, like in 19th century grammar schools. Our goal is not for learners to regurgitate facts by rote without demonstrating their understanding of the connections, structures, and deeper ideas embedded in the content they are learning. To foster critical thinking in school, especially for our youngest learners, we need a pedagogy that centers knowledge and also honors the ability of children to engage with knowledge.

This chapter outlines the Critical Thinking Framework: five instructional approaches educators can incorporate into their instruction to nurture deeper thinking. These approaches can also guide intellectual preparation protocols and unit unpackings to prepare rigorous, engaging instruction for elementary students. Some of these approaches, such as reason with evidence, will seem similar to other “contentless” programs professing to teach critical thinking skills. But others, such as say it in your own words or look for structure, are targeted at ensuring learners soundly understand content so that they can engage in complex thinking. You will likely notice that every single one of these approaches requires students to talk—to themselves, to a partner, or to the whole class. Dialogue, specifically in the context of teacher-led discussions, is essential for students to analyze, evaluate, and judge (i.e., do critical thinking ).

The Critical Thinking Framework

Say it in your own words : Students articulate ideas in their own words. They use unique phrasing and do not parrot the explanations of others. When learning new material, students who pause to explain concepts in their own words (to themselves or others) demonstrate an overall better understanding than students who do not (Nokes-Malach et al., 2013). However, it’s not enough for us to pause frequently and ask students to explain, especially if they are only being asked to repeat procedures. Explanations should be effortful and require students to make connections to prior knowledge and concepts as well as to revise misconceptions (Richey & Nokes-Malach, 2015).

Break it down : Students break down the components, steps, or smaller ideas within a bigger idea or procedure. In addition to expressing concepts in their own words, students should look at new concepts in terms of parts and wholes. For instance, when learning a new type of problem or task, students can explain the steps another student took to arrive at their answer, which promotes an understanding that transfers to other tasks with a similar underlying structure. Asking students to explain the components and rationale behind procedural steps can also lead to more flexible problem solving overall (Rittle-Johnson, 2006). By breaking down ideas into component parts, students are also better equipped to monitor the soundness of their own understanding as well as to see similar patterns (i.e., regularity) among differing tasks. For example, in writing, lessons can help students see how varying subordinating conjunction phrases at the start of sentences can support the flow and readability of a paragraph. In math, a solution can be broken down into smaller steps.

Look for structure : Students look beyond shallow surface characteristics to see deep structures and underlying principles. Learners struggle to see regularity in similar problems that have small differences (Reed et al., 1985). Even when students are taught how to complete one kind of task, they struggle to transfer their understanding to a new task where some of the superficial characteristics have been changed. This is because students, especially students who are novices in a domain, tend to emphasize the surface structure of a task rather than deep structure (Chi & Van Lehn, 2012).

By prompting students to notice deep structures—such as the characteristics of a genre or the needs of animals—rather than surface structures, teachers foster the development of comprehensive schemata in students’ long-term memories, which they are more likely to then apply to novel situations. Teachers should monitor for student understanding of deep structures across several tasks and examples.

Notice gaps or inconsistencies in ideas : Students ask questions about gaps and inconsistencies in material, arguments, and their own thinking . When students engage in explanations of material, they are more likely to notice when they misunderstand material or to detect a conflict with their prior knowledge (Richey & Nokes-Malach, 2015). In a classroom, analyzing conflicting ideas and interpretations allows students to revise misconceptions and refine mental models. Noticing gaps and inconsistencies in information also helps students to evaluate the persuasiveness of arguments and to ask relevant questions.

Reason with evidence : Students construct arguments with evidence and evaluate the evidence in others’ reasoning. Reasoning with evidence matters in every subject, but what counts for evidence in a mathematical proof differs from what is required in an English essay. Students should learn the rules and conventions for evidence across a wide range of disciplines in school. The habits of looking for and weighing evidence also intersect with some of the other critical thinking approaches discussed above. Noticing regularity in reasoning and structure helps learners find evidence efficiently, while attending to gaps and inconsistencies in information encourages caution before reaching hasty conclusions.

Countering Two Critiques

Some readers may be wondering how the Critical Thinking Framework differs from other general skills curricula. The framework differs in that it demands application in the context of students’ content knowledge, rather than in isolation. It is a pedagogical tool to help students make sense of the content they are learning. Students should never sit through a lesson where they are told to “say things in their own words” when there is nothing to say anything about. While a contentless lesson could help on the margins, it will not be as relevant or transferable. Specific content matters. A checklist of “critical thinking skills” cannot replace deep subject knowledge. The framework should not be blindly applied to all subjects without context because results will look quite different in an ELA or science class.

Other readers may be thinking about high-stakes tests: how does the Critical Thinking Framework fit in with an overwhelming emphasis on assessments aligned to national or state standards? This is a valid concern and an important point to address. For teachers, schools, and districts locked into an accountability system that values performance on state tests but does not communicate content expectations beyond general standards, the arguments I make may seem beside the point. Sure, knowledge matters, but the curriculum demands that students know how to quickly identify the main idea of a paragraph, even if they don’t have any background knowledge about the topic of the paragraph.

It is crucial that elementary practitioners be connected to both evolving research on learning and the limiting realities we teach within. Unfortunately, I can provide no easy answers beyond saying that teaching is a balancing act. The tension, while real and relevant to teachers’ daily lives, should not cloud our vision for what children need from their school experiences.

I also argue it is easier to incorporate the demands of our current standardized testing environment into a curriculum rich with history, science, art, geography, languages, and novels than the reverse. The Critical Thinking Framework presents ways to approach all kinds of knowledge in a way that presses students toward deeper processing of the content they are learning. If we can raise the bar for student work and thinking in our classrooms, the question of how students perform on standardized tests will become secondary to helping them achieve much loftier and important goals. The choice of whether to emphasize excellent curriculum or high-stakes tests, insofar as it is a choice at all, should never be existential or a zero-sum game.

From Critical Thinking in the Elementary Classroom: Engaging Young Minds with Meaningful Content (pp. 25–29) by Erin Shadowens, Arlington, VA: ASCD. Copyright © 2023 by ASCD. All rights reserved.

Teaching Critical Thinking

Help your students develop their critical thinking skills with these lesson plans. “Could Lincoln Be Elected Today?” is a resource developed from a Annenberg Public Policy Center political literacy project called FlackCheck. All the other critical thinking lessons were produced by the FactCheck.org education project called FactCheckEd.

Could Lincoln Be Re-elected Today?

FlackCheck.org, a political literacy project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, compares ads from the 2020 presidential election to a series of ads that it created using modern-day tactics for the 1864 Lincoln vs. McClellan race to help students recognize patterns of deception and develop critical thinking skills.

“Could Lincoln Be Elected Today?”

This lesson uses a series of ads that were created using modern-day tactics for the 1864 Lincoln vs. McClellan race. Students will learn to recognize flaws in arguments in general and political ads in particular and to examine the criteria for evaluating candidates, past and present, for the presidency.

Background Beliefs

We’ve all had that experience, the one where we start arguing with someone and find that we disagree about pretty much everything. When two people have radically different background beliefs (or worldviews), they often have difficulty finding any sort of common ground. In this lesson, students will learn to distinguish between the two different types of background beliefs: beliefs about matters of fact and beliefs about values. They will then go on to consider their most deeply held background beliefs, those that constitute their worldview. Students will work to go beyond specific arguments to consider the worldviews that might underlie different types of arguments.

Building a Better Argument

Whether it’s an ad for burger chains, the closing scene of a “Law & Order” spin-off, a discussion with the parents about your social life or a coach disputing a close call, arguments are an inescapable part of our lives. In this lesson, students will learn to create good arguments by getting a handle on the basic structure. The lesson will provide useful tips for picking out premises and conclusions and for analyzing the effectiveness of arguments.

Language of Deception

It’s a phased withdrawal, not a retreat. Except that the terms actually mean the same thing. But “retreat” sounds much worse, so savvy politicians avoid using it. That’s because they understand that there is a difference between the cognitive (or literal) meaning and the emotive meaning of a word. This lesson examines the ways in which terms that pack an emotional punch can add power to a statement – and also ways in which emotive meanings can be used to mislead, either by doing the reader’s thinking for him or by blinding her to the real nature of the issue.

Everything You Know Is Wrong 1: Us and Them

Good reasoning doesn’t come naturally. In fact, humans are instinctively terrible reasoners. Most of the time, the way our brains work isn’t rational at all. Even with exceptional training in analytical thinking, we still have to overcome instincts to think simplistically and nonanalytically. In this lesson, students explore some of the irrational ways in which humans think, and learn to recognize and overcome the habits of mind that can get in the way of good reasoning. Here we focus on the ways that people define themselves and others — how we develop our personal and group identities, how we treat people whose identities are similar or different, and how this affects our perceptions and our ability to reason.

Everything You Know Is Wrong 2: Beliefs and Behavior

Good reasoning doesn’t come naturally. In fact, humans are instinctively terrible reasoners — most of the time, the way our brains work isn’t rational at all. Even with exceptional training in reasoning skills, we still have to overcome instincts to think simplistically and non-analytically. This is the second of two lessons focusing on the instincts and habits of mind that keep us from thinking logically. In the first one, we looked at how people define themselves, alone and in groups, and how this affects behavior. This time around, we will focus on how people reconcile their beliefs with the world around them, even when the evidence doesn’t seem to agree with those beliefs.

Monty Python and the Quest for the Perfect Fallacy

If you weigh the same as a duck, then, logically, you’re made of wood and must be a witch. Or so goes the reasoning of Monty Python’s Sir Bedevere. Obviously, something has gone wrong with the knight’s reasoning – and by the end of this lesson, you’ll know exactly what that is. This lesson will focus on 10 fallacies that represent the most common types of mistakes in reasoning.

Oil Exaggerations

Ever notice how political speeches and ads always mention “the worst,” “the best,” “the largest,” “the most”? It’s effective to use superlatives, but it isn’t always accurate. For instance, President Barack Obama has said that “we import more oil today than ever before” – but do we? How can you find out? What do the numbers really mean? And why would he say it if it wasn’t true? In this lesson, students will weigh Obama’s superlative claim against the facts.

The Credibility Challenge

The Internet can be a rich and valuable source of information – and an even richer source of misinformation. Sorting out the valuable claims from the worthless ones is tricky, since at first glance a Web site written by an expert can look a lot like one written by your next-door neighbor. This lesson offers students background and practice in determining authority on the Internet – how to tell whether an author has expertise or not, and whether you’re getting the straight story.

Peta Pressure

Persuading an audience requires intensive research and scrupulous fact-checking – or, you could just figure out what your audience wants to hear and tell them that. Politicians, advertisers and others with something to sell choose words and images that will appeal to their target audience, enticing them to accept claims unquestioningly. Some of these manipulators, like the animal activism site peta2.com, focus their attentions on teenagers and young adults. In this lesson, students won’t check peta2’s factual accuracy, but will learn to spot their manipulative tactics and why they should be skeptical about them.

The Battle of the Experts

When we hear a piece of information that surprises us, we often react by saying, “Where’d you hear that?” It’s a good question, and one we should ask more often, because some sources are better – sometimes much better – than others. In this lesson, students will learn to distinguish between credible and not-so-credible types of sources. They’ll explore the biases of different sources and develop tools for detecting bias. In their effort to get to facts that are as objective as possible, students will examine the differences between primary and secondary sources, check the track records of different sources, and practice looking for broad consensus from a range of disinterested experts.

U.S. Generals…Support the Draft

Being drafted hasn’t been much of a concern for anyone born on this side of the Age of Aquarius. But rumors of the return of the draft abound. Those rumors are especially scary when they seem to originate from U.S. military commanders. This lesson examines an anti-war advertisement sponsored by Americans Against Escalation in Iraq asserting that military officials plan to continue the war in Iraq for an additional 10 years and that that plan will require reinstating the draft. Students will examine whether quotations from Gen. David Petraeus and Lt. Gen. Douglas Lute really do support AAEI’s claims.

In the good old days, back in January 2007, gas cost just $2.20 per gallon. Your parents might even remember those four months in 1998–1999 when it dropped below $1 per gallon. And your grandparents can likely tell you stories about filling the tank for $5 — or about the cost per gallon in some parts of the U.S. in July 2008. That’s when presumptive Republican presidential nominee John McCain ran an ad promoting his plan for bringing down the cost of gas. According to McCain, gas prices were high because some politicians still opposed lifting a ban on offshore oil drilling. But McCain’s ad left out some basic facts about offshore drilling. In this lesson, students will examine the facts behind McCain’s false connections. This lesson comes in a basic version, for classrooms without internet access and/or students at the 8th-9th grade level, and a more advanced version, which does require internet access and is aimed at students at higher grade levels.

Olly Olly Oxen Free

You find the perfect hiding spot and you wait, hoping to hear that magical sound, to hear whoever is “it” call out in frustration, “Olly Olly Oxen Free!” You know that you’re safe, that your hiding spot – your sanctuary – can be used again the next time you play. But in debates about people who are in the U.S. illegally, the concept of sanctuary is considerably more controversial. In fact, some argue that providing sanctuary to people who are in the country illegally is decidedly wrong. This lesson focuses on an argument between former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney and former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani over New York’s alleged status as a sanctuary city for illegal immigrants. Students will explore the meaning of the term “sanctuary city” and determine for themselves whether New York City ought to be designated a sanctuary city.

Made in the U.S.A.

It seems as if fewer and fewer things bear that label anymore. In 2007, Toyota outsold two of Detroit’s big three automakers. Our televisions and DVD players are mostly made elsewhere. And Walmart imports about 50,000 pounds of merchandise every 45 seconds. As if that’s not bad enough, American companies are shipping many jobs overseas. Democratic presidential candidate John Edwards wanted to stop U.S. companies from moving jobs offshore, and a group called Working 4 Working Americans ran an ad in support of his plan. But the story the ad tells doesn’t quite give the whole picture. In this lesson, students will examine the facts behind this potentially misleading ad. This lesson comes in a basic version, for classrooms without internet access and/or students at the 8th-9th grade level, and a more advanced version, which does require internet access and is aimed at students at higher grade levels.

Health Care Hooey

“Candidate X will raise your taxes!” “Candidate Y will take away your health care!” In the hotly contested 2008 presidential election, one ad from Democrat Barack Obama created the perfect storm of election themes, accusing Republican John McCain of planning to increase taxes on your health care. But the ad used outdated sources to justify its claims. In this lesson, students will draw on independent experts to determine the accuracy of Sen. Obama’s charge. This lesson comes in a basic version, for classrooms without internet access and/or students at the 8th-9th grade level, and a more advanced version, which does require internet access and is aimed at students at higher grade levels.

Combating the Culture of Corruption

It’s a classic American film: the young, idealistic new senator, Jefferson Smith, heads off to Washington where he finds that his boyhood hero, Sen. Joseph Paine, is accepting bribes. Worse still, Mr. Smith finds that none of the other senators really care all that much. In Hollywood, the solution is simple: Jimmy Stewart saves the day. Fast forward 60 years: The corruption is still around, and in a fundraising e-mail, the Democratic National Committee claims that presumptive Republican presidential nominee Sen. John McCain is more Joseph Paine than Jefferson Smith. That charge has little basis in reality. In this lesson students will dig into a bribery scandal to assess John McCain’s real role in rooting out the culture of corruption.

- Cornette Library

Critical Thinking

Lesson ideas & tools.

- Confirmation Bias

- Deepfake Videos

- Evaluation Tools & Search Strategies

- Logic Puzzles

- Open Educational Resources

- Quiz and Certificate

- Bloom's Taxonomy Use Bloom's Taxonomy to help your students achieve a higher level of thinking.