Climate Change and Constitutional Overreach

Drake Law Review (Forthcoming)

Case Legal Studies Research Paper No. 11

33 Pages Posted: 10 Sep 2024

Jonathan H. Adler

Case Western Reserve University School of Law; PERC - Property and Environment Research Center

Date Written: July 26, 2024

The failure of the political process to produce meaningful policies to mitigate the threat of climate change has encouraged aggressive and innovative litigation strategies. An increasing number of climate lawsuits seek to control greenhouse gas emissions, impose liability on fossil fuel producers, or otherwise force greater action on climate change. In many of these cases, litigants have made aggressive constitutional claims that stretch the bounds of existing constitutional doctrine. This essay, prepared for the 2024 Drake University Constitutional Law Center Symposium, "Climate Change, the Environment, and Constitutions," critically assesses some of the constitutional arguments made in climate cases, including Massachusetts v. EPA and Juliana v. U.S ., as well as some of the constitutional claims made by states opposing efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Jonathan H. Adler (Contact Author)

Case western reserve university school of law ( email ).

11075 East Boulevard Cleveland, OH 44106-7148 United States 216-368-2535 (Phone) 216-368-2086 (Fax)

HOME PAGE: http://www.jhadler.net

PERC - Property and Environment Research Center

2048 Analysis Drive Suite A Bozeman, MT 59718 United States

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, case research paper series in legal studies.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

U.S. Administrative Law eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Law & Culture eJournal

Law & economics ejournal, environmental law & policy ejournal, risk, regulation, & policy ejournal, energy law & policy ejournal.

The Rise of Climate Litigation

Shagun Agarwal is a Climate Solutions Associate at ISS ESG. This post is based on his ISS memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here ); Companies Should Maximize Shareholder Welfare Not Market Value by Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales (discussed on the Forum here ); and Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: The Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee by Max M. Schanzenbach and Robert H. Sitkoff (discussed on the Forum here ).

Climate litigation is an increasingly common and accessible area of environmental law, and is being used to hold countries and public corporations to account for their climate mitigation efforts and historical contributions to the problem of climate change.

A Global Surge in Litigation

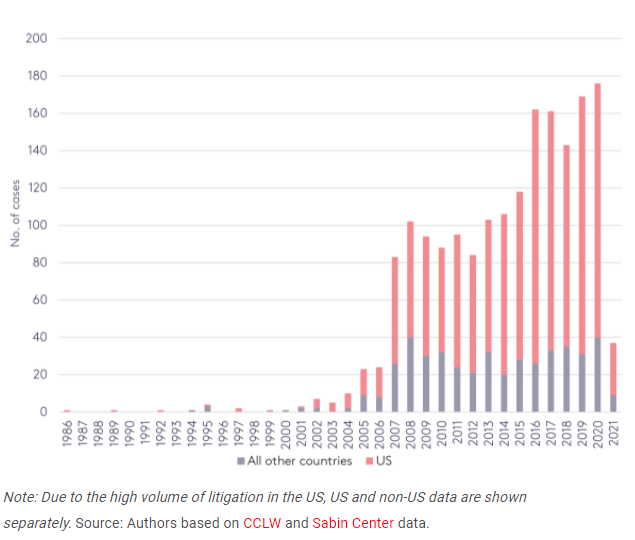

There is a clear upward trend in the use of climate litigation. Until 2017, the total number of climate litigation cases was 884 across a total of 24 countries, with 654 of these cases being in the United States. By 2020, this number had nearly doubled to 1,550 cases across 38 countries.

Figure 1. Climate Litigation, 1986-2021

Source: Global Trends in Climate Litigation , London School of Economics, 2021

Consequently, litigation risk is emerging as an expanding subset of both physical and transition risks. With the varying validity of the multitude of Net Zero claims being made, this risk becomes an even more important aspect to be considered.

The cases have so far broadly fallen into one or a combination of six major categories :

- Climate rights

- Domestic enforcement

- Keeping fossil fuels in the ground

- Corporate liability and responsibility

- Failure to adapt and the impacts of adaptation

- Climate disclosures and greenwashing

Figure 2. Climate Litigation Categories

Source: Global Climate Litigation Report, 2020

While each category has seen a wide spectrum of scrutiny, there has been a growing focus on climate disclosures and greenwashing. Because of growing awareness, accessibility, and disclosure requirements, countries and increasingly corporations find themselves being held to account for their climate mitigation pledges and consequent environmental impact, by investors and stakeholders alike.

Holding Corporations Accountable for Impacts on Climate Change

The current rate of increase in cases against private and financial sector actors indicates more diversity and complexity in the arguments that are being used, particularly those based on notions of fiduciary duty and greenwashing.

Examples of the growing standards of accountability that are now being legally levied include the following cases:

- The York County v. Rambo case (pending), where bond investors accused the Pacific Gas and Electric Company of failing to disclose the risk of its non-compliance with electrical line maintenance standards and consequent contribution to increasing wildfires in the region.

- Friends of the Earth et al. v. Prefect of Bouches-du-Rhône and Total where the Administrative Court of Marseille invalidated Total’s permit to operate a biorefinery and ordered a deeper study of the climate impacts of palm oil production.

- McVeigh v Retail Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd , where a member of a super fund known generally as ‘Rest’ claimed the fund was in breach of Australia’s Corporations Act 2001 due to failure to provide information on how Rest was managing climate change risks. Although resolved in an out-of-court settlement, the case has set a strong precedent for acknowledging the material risk climate change poses for institutional investors.

Similar rulings across other categories continue to set a stronger global precedent for individuals and organizations to utilize legal avenues in their efforts to drive action on climate change.

In a landmark 2021 case ( Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell ), a group of Dutch NGOs won a ruling against global energy company Royal Dutch Shell. The premise of the argument was rooted in the unwritten standard of care found in Section 162 of the Dutch Civil Code. After four days of hearings, the Court concluded that:

“The standard of care included the need for companies to take responsibility for Scope 3 emissions, especially where these emissions form the majority of a company’s CO2 emissions, as is the case for companies that produce and sell fossil fuels.”

As a result, Shell was ordered to reduce Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions across its entire energy portfolio by 45% relative to 2019 emission levels by 2030.

Investors’ Response to Climate Litigation

The impact of such hearings and their potential repercussions raise questions around what investors should be doing, and what comes next?

There are three key aspects which require consideration:

- The need to acknowledge climate litigation as an evolving and integral risk to investee corporation operations and investment growth.

- The incorporation of litigation risk into assessments of climate-related financial risks and the integration of litigation risk into investment growth modeling.

- Encouraging comprehensive disclosure to mitigate the legal risks as much as possible.

The growing occurrences of natural disasters, whether extreme flooding in Germany , sweltering heat waves in the US and Canadian Pacific Northwest, raging bushfires in Australia, or record typhoons and cyclones in Thailand, have become deeply emblematic of a world increasingly affected by climate change.

The global scope and varying intensity of climate change events not only poses a direct risk to investors’ physical assets, but it also underscores the consequent risk of and need for transitioning towards a low-carbon economy. Therefore, adding to these risks the risk of potential legal action emphasizes how climate litigation is not just an additional dimension to physical and transition risk, but a separate risk to be assessed.

Addressing these conditions and their interplay through more robust emissions data and diligent reporting is therefore imperative, not just for corporations and investors, but for asset owners and managers as well. As investors, corporations, and countries plan and progress in their respective Net Zero transitions, such legal battles are only going to multiply in the coming years.

One Comment

As a debater, this article is one of the most useful thing’s I’ve ever found. It completely non-uniques the litigation DA. Subodh Mishra, you are a savior and forever in my heart.

Supported By:

Subscribe or Follow

Program on corporate governance advisory board.

- William Ackman

- Peter Atkins

- Kerry E. Berchem

- Richard Brand

- Daniel Burch

- Arthur B. Crozier

- Renata J. Ferrari

- John Finley

- Carolyn Frantz

- Andrew Freedman

- Byron Georgiou

- Joseph Hall

- Jason M. Halper

- David Millstone

- Theodore Mirvis

- Maria Moats

- Erika Moore

- Morton Pierce

- Philip Richter

- Elina Tetelbaum

- Marc Trevino

- Steven J. Williams

- Daniel Wolf

HLS Faculty & Senior Fellows

- Lucian Bebchuk

- Robert Clark

- John Coates

- Stephen M. Davis

- Allen Ferrell

- Jesse Fried

- Oliver Hart

- Howell Jackson

- Kobi Kastiel

- Reinier Kraakman

- Mark Ramseyer

- Robert Sitkoff

- Holger Spamann

- Leo E. Strine, Jr.

- Guhan Subramanian

- Roberto Tallarita

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish

- About Journal of Environmental Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- JEL Workshops

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. climate change and human rights, 3. statutory interpretation, climate change and rights, 4. the development, meaning and use of the principle of legality, 5. making the link between climate change, fundamental rights, and statutory interpretation, 6. the value of principle of legality-reasoning, 7. conclusion.

- < Previous

Climate Change, Fundamental Rights, and Statutory Interpretation

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ceri Warnock, Brian J Preston, Climate Change, Fundamental Rights, and Statutory Interpretation, Journal of Environmental Law , Volume 35, Issue 1, March 2023, Pages 47–64, https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqad002

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The climate change crisis demands a wholesale transformation of law. In this article, we consider one potential component of that transformation: the role that rights-protective statutory interpretation might play. Specifically, we analyse the transformative potential of the principle of legality. The principle of legality is a presumption of statutory interpretation that legislation should not be read as infringing fundamental common law rights in the absence of irresistibly clear statutory language. It enables courts to give statutory words their least rights-infringing meaning. The law in international fora and domestic jurisdictions now acknowledges that climate change will adversely affect human rights. We make the linkage between climate change, fundamental rights, and statutory interpretation and argue that the principle of legality may, in appropriate cases, be used to interpret legislation regulating the range of human activity, in a climate-protective way.

To address the challenge of climate change, commentators suggest that there needs to be a wholesale transformation of the economy. 1 But there also needs to be a wholesale transformation of law. Such transformation requires integration—integration between policy, legislation, legal reasoning, and adjudicative decision-making. 2 In relation to the latter, Joanna Bell and Liz Fisher have posed the question: What does it mean ‘to “adjudicate well” in relation to climate change legislation and thus... incorporate ‘climate change into the substructure of the law’? 3 Given the current, precarious state of the environment, there may be a temptation to seek answers in legal revolution. However, as Fisher counsels, ‘legal pasts’ should not be abandoned in this endeavour but rather drawn upon as a resources for present and future legal reasoning. 4

In this article, we take inspiration from Fisher and draw upon legal reasoning rooted in legal pasts to facilitate one possible component of that transformation. We consider the role that statutory interpretation might play in ensuring that climate change considerations infuse decision-making throughout the legal landscape. Specifically, our focus is the linkage between climate change, fundamental rights, and a common law principle of statutory interpretation, that is: the principle of legality. 5

Our argument and the structure of this article is as follows: in Section 2, we demonstrate that the law in many international fora and domestic jurisdictions now acknowledges that climate change impacts will adversely affect fundamental human rights. As we discuss, the rights impacted include the right to life, right to the fundamental conditions of life, liberty and security of the person, and the protection of indigenous lands and culture.

Section 3 explains the role that statutory interpretation plays in linking rights-based reasoning and climate change considerations. To be clear, we are not considering how human rights could be used to interpret statutes directly; such an approach misses an important link in legal reasoning. Rather we are considering how statutes might be interpreted using the principle of legality, and the application of the principle necessitates a stepped process as we discuss.

Section 4 explores the principle of legality. In brief, the principle of legality is a common law canon of statutory construction that may be employed in circumstances where a party alleges legislation should be interpreted in a way so as not to infringe fundamental human rights, freedoms, and values—and those rights may have been created by legislative instrument or the common law. Where there is a choice of statutory construction, the principle requires a court to choose the interpretation that better upholds human rights. Accordingly, the principle has an important rule of law function; it can be and is being used by courts to protect fundamental human rights. The principle of legality can be used to interpret all legislative forms: from constitutions, and primary legislation, to regulations and by-laws. Its use can impact both the outcome of cases and enrich legal doctrine, as we explain below. It is important to note that while many bills of rights contain interpretative provisions that have similar effect to the principle of legality, 6 they do not usurp or replace that common law canon. 7 Accordingly, the principle of legality is a tool that exists in judicial reasoning whether nations have enacted bills of rights or not.

In Section 5, we demonstrate how, in appropriate cases, the principle of legality can be used to bring climate change considerations into adjudicative decision-making via rights-based reasoning. For example, if interpreting legislation in one way will allow for an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, leading to greater climate change impacts and a correlative impact on rights, the principle of legality requires the court to explore if there are equally available ways of interpreting the legislation that would not infringe human rights. Accordingly, in appropriate scenarios, the principle of legality will allow climate change considerations to infuse adjudicative decision-making via the process of statutory interpretation. Note, we do not confine our argument to the interpretation of specific schemes promulgated to address climate change—it does not matter if the legislation has climate change as its focus or not— all legislation, governing every aspect of human ordering, may be susceptible to the principle of legality analysis we propose.

Finally, in Section 6, we consider why the use of the principle might be advantageous and what gaps in the existing law it fulfils—particularly in this age of rights instruments. Our analysis relies predominantly on the law in New Zealand and Australia, with some discussion of the situation in the UK, however the principle of legality is employed in many common law countries and our argument may well be adaptable to other jurisdictions. In Section 7, we conclude.

We acknowledge that embedding climate change considerations into the ‘substructure of the law’ 8 relies upon ‘climate conscious lawyering’, 9 that is, an active awareness on the part of lawyers ‘of the reality of climate change and how it interacts with daily legal problems’. 10 But consciousness alone is not enough. Lawyers are still required to draw upon existing legal tools to make climate-protective arguments. As we argue, the principle of legality supports reasoning that legislation should be interpreted in as climate-protective a way as possible, and used in this way the principle can help infuse climate change considerations into the wider law.

Before considering the principle of legality in greater detail, we must first lay out the foundational aspect to our argument, that is the link between climate change and human rights. There is, of course, a long history of human rights law being used to protect environmental interests. 11 Further, the clear factual and legal link between climate change and the abrogation of fundamental human rights is no longer conjecture, rather it has been affirmed in various international fora and judicial decisions around the world. 12

Reflecting the growing consensus internationally, the link between climate change and human rights is acknowledged in the Preamble to the Paris Agreement, 13 and has been formally accepted in resolutions by the United Nations Human Rights Council, 14 and various regional commissions and assemblies. 15 It is possible to trace the trajectory of reasoning in the United Nations Human Rights Committee (UN HRC)—from a willingness to acknowledge environmental impacts on rights 16 to the acceptance that climate change provides a valid basis for relief. In Teitiota v New Zealand , 17 the UN HRC accepted that the impact of climate change and associated sea level rise threatened the habitability and security of inhabitants on Kiribati, and created a real risk of impairment to the right to life under Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in principle, albeit the claim for refugee status was unsuccessful on the specific facts. 18 Most recently, in Torres Strait Eight v Australia , 19 eight Torres Strait Islander people and six of their children brought a complaint to the UN HRC against the Australian government, alleging that Australia violated their rights under Articles 6 (the right to life), 17 (the right to be free from arbitrary interference with privacy, family and home) and 27 (the right to culture) of the ICCPR due to the government’s failure to address climate change. The Committee found in favor of the claimants, holding that Australia had violated their rights to culture and to be free from arbitrary interference with privacy, family and home, but not the right to life. In reaching this conclusion, the Committee considered the claimants’ close, spiritual connection with their traditional lands, and the dependence of their culture on the health of the surrounding ecosystems. 20 While the majority of the Committee held that there was currently no violation of the claimants’ right to life, it recognised that ‘without robust national and international efforts, the effects of climate change may expose individuals’ to such a violation. 21 Individual opinions issued by the minority of the Committee, however, did find that the claimants’ right to life had already been violated. 22

Writing in 2018, following the successful cases of Leghari v Federation of Pakistan 23 and Urgenda v The Netherlands , 24 Peel and Osofsky reported ‘a growing receptivity’ of domestic courts to the framing of climate change litigation in human rights terms. 25 Other scholars have mapped the relevant litigation by considering the type of claims pleaded, role of rights in submissions, relevant actors, forms of rights impacted, degrees of success and remedies. 26 As one of us discusses in a recent article, claims at the domestic level fall into three main causes of action premised upon breaches of international and regional treaties, constitutional rights, and rights in statutory instruments, and some encompass a combination of those claims. 27 It is not the purpose of this study to closely analyse or catalogue those cases; interested readers are referred to the relevant literature. Our focus is to demonstrate how a principle of statutory construction may be used to interpret statutes in a way that upholds human rights and in doing so, address climate change. Accordingly, the important point for our argument is that numerous cases in jurisdictions around the world, have now acknowledged the factual link between climate change and human rights . The rights impacted include: the right to life; 28 the fundamentals of life; 29 the dignity of the person; 30 liberty and the security of the person; 31 privacy; 32 and family and home life. 33 Other cases currently before the courts, rely on additional causes of action, including breaches of indigenous rights to ancestral lands and cultures, 34 the right not to be discriminated against, 35 and the protection of private property. 36 Climate change is likely to impact multiple rights and many cases plead the risk to or breach of overlapping rights. 37 Cases decided in the last few years illustrate how the link between climate change and human rights is becoming increasingly accepted factually and proving legally determinative in different ways. Four recent cases illustrate this legal diversity.

Neubauer et al v Germany , 38 for example, involved a constitutional complaint regarding Germany’s Federal Climate Protection Act (the Bundesklimaschutzgesetz ). The young complainants challenged the Climate Protection Act on the basis that the emission reduction targets were insufficient and violated their human rights as protected under the Constitution of Germany, the Basic Law ( Grundgesetz ), including the right to life and physical integrity [Article 2(2)], right to property [Article 14(1)] and right to the protection of ‘natural sources of life’ (Article 20a). The German Constitutional Court held that the failure of the Climate Protection Act to set greenhouse gas emission reduction targets beyond 2030 limited inter-temporal guarantees of freedom. 39

In Milieudefensie et al v Royal Dutch Shell plc , 40 Milieudefensie and six other plaintiffs alleged that Royal Dutch Shell (RDS) committed a tortious act and violated its duty of care under the Dutch Civil Code by emitting greenhouse gas emissions that contributed to climate change. In interpreting Article 6:162 of the Code, the District Court of The Hague drew on the ICCPR and the European Convention of Human Rights and cited Urgenda v The Netherlands . 41 The Court found that climate change threatens the right to life and the right to respect for private and family life of Dutch residents and the inhabitants of the Wadden region. 42 The Court ordered RDS to reduce net emissions across its portfolio by 45% by 2030. 43

Waratah Coal Pty Ltd v Youth Verdict Ltd and Ors 44 is the first case to emerge from Queensland’s Human Rights Act 2019 (HRA 2019). The case concerned applications for a mining lease and an environmental authority for a new coal mine before the Queensland Land Court. The objectors submitted that a decision to grant a mining lease and an environmental authority for the mine would be unlawful under s 58(1) of HRA 2019. Waratah Coal, applied to strike out the human rights objections to the extent that they relied on the HRA 2019 or, in the alternative, obtain a declaration that the Land Court does not have jurisdiction and was not obliged to consider those objections. 45 The Land Court rejected the strike out application and held that human rights considerations apply to the Land Court in making its recommendations on applications for a mining lease and an environmental authority as it is compelled by the HRA 2019, as a public entity, to make a decision in a way that is compatible with human rights. 46 The Land Court confirmed that objectors would be entitled to seek relief in the event the Court failed to make a recommendation compatible with human rights. 47 In giving final judgment, the Court accepted that the mining and (inevitable) burning of the coal would increase climate change impacts and breach a range of human rights. 48 Accordingly, the Court recommended that the Minister decline consent, as permission would constitute a breach of the Minister’s duties under the HRA 2019 to protect rights.

Another recent example of litigation premised on statutory rights is Mathur v Ontario , 49 an application by Ontario to strike out a claim brought by young people against government inaction on climate change. In dismissing the strike out application, the Court accepted the prima facie nature of the applicants’ claims that climate change could ‘increase the risk of death’ 50 and ‘interfere with the Applicants’ ability to choose where to live... [so engaging] the ‘liberty’ interest in s 7 [of The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982]. 51 The Court also accepted that government inaction on climate change could lead ‘to an increase in serious psychological harm and mental distress... [and] prima facie engages the security [of the person] interest in s 7’. 52

None of the cases referenced above rely upon the principle of legality-argument that we posit; rather, all show how courts have started the journey of linking climate change and human rights in different legal contexts. Our purpose in this article is to advance that progress by showing how one legal tool could be used to develop the climate-rights relationship across different types of adjudication.

Having illustrated the link between climate change and rights in the previous section, we move to considering the role that statutory interpretation might play as a mechanism to secure that link in legal reasoning. Mathur and Waratah Coal aside, many of the successful cases referenced in part one are based on breaches of justiciable rights in codified constitutions. 53 Nevertheless, this development raises an intriguing possibility for lawyers in nations without those constitutional foundations but with extensive statute-based law, such as New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom: Could that ‘climate change-rights linkage’ inform statutory interpretation , and by so doing ensure climate change considerations infuse the wider law in those nations?

There are three possible legal routes for this wider infusion to occur. First, courts in each of those nations draw upon international treaty law, including international human rights treaties, to inform the interpretation of domestic statutes where appropriate. Australia, New Zealand and the UK are dualist states; they have ratified various international human rights treaties; 54 and these commitments have been imported into domestic law in various ways. 55 Some jurisdictions have empowered courts to interpret domestic law in a way that is compatible with international law and human rights instruments, by enacting legislative provisions. 56 Nevertheless, there is common law authority in each nation providing that courts will interpret domestic legislation consistently with international treaty law commitments where possible, whether or not the legislation was enacted with the purpose of implementing the relevant treaty text. 57

Second, both New Zealand and the United Kingdom have statutory bills of rights that require courts to interpret legislation in a manner consistent with the enumerated rights where possible—New Zealand has s 6 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 and the UK has s 3(1) of the Human Rights Act 1998—and three Australian states have similar legislative provisions: Queensland, Victoria, and the Australian Capital Territory. 58 Although all statutory formulations are slightly different, 59 and a complex jurisprudence has built up around the application of the provisions, 60 the core premise that interpretation be compatible with rights where possible is consistent across jurisdictions. 61

Third, courts in all three nations draw upon the principle of legality in interpreting legislation to protect fundamental common law rights. As we explain below, broadly understood, the principle of legality is a common law principle of statutory interpretation that favors rights-consistent interpretations of legislation where possible. Each of these three potential legal routes demand careful scholarly attention, but in this article we focus solely on the lesser known principle of legality and the role that it might play, for good reasons as we explain in Section 6.

In this part, we explain the principle of legality. Our purpose is not to critique the principle from an academic perspective, question whether it is constitutionally defensible, or map the entire scholarly literature. Rather, we are concerned with explaining the principle in sufficient detail to advance our argument.

The principle of legality is a presumption of statutory construction that protects fundamental rights, freedoms, and values against infringement by general or ambiguous legislation. The principle is of ancient pedigree, emerging in the common law courts of England in the 1600s 62 and crystallising in the mid 1800s, 63 although it did not attract the modern moniker until much later. 64 The principle appeared in other jurisdictions, such as the USA and Australia in the 18th and 19th centuries, 65 and today is employed in common law jurisdictions around the world. 66

Initially, the principle was encapsulated in the idea that ‘a statute is not to be taken as effecting a fundamental alteration in the general law unless it uses words which point unmistakably to that conclusion’. 67 Historically, that approach has been said by some to reflect the resistance of the common law judges to incursions by statute law in an era where the constitutional principle of parliamentary sovereignty had not fully fomented. 68 Over time, however, that traditional rationale narrowed. With the rise of the welfare state and the resulting ‘orgy of statute making’, 69 it was no longer reasonable for the courts to assume that governments did not want to supplant the common law with legislation. 70 There was a shift in focus and the principle came to be seen as a way of protecting fundamental rights in person and property. Sales LJ captures the modern focus, explaining extra-judicially that, ‘[u]nder the principle of legality, a fundamental right is treated as respected by a statutory provision unless abrogated by express language or clear necessary implication’. 71

In early cases, the courts presumed that Parliament would not intend infringement of rights in the absence of irresistibly clear statutory language and so relied upon ‘an anterior assumption about legislative intention’. 72 The courts credited legislatures with a sincere intention not to override rights without careful thought and deliberate action. The fundamental nature of the protected rights meant that the courts attributed to Parliament clear knowledge of those rights when passing legislation and the need to be explicit if it intended to remove those rights. However, more recent cases have tended not to rest upon the rationale of prior parliamentary intent. In R v. Secretary of State for the Home Dept, ex p Simms , Lord Hoffmann explained 73 :

Parliamentary sovereignty means that Parliament can, if it chooses, legislate contrary to fundamental principles of human rights.... The constraints upon its exercise by Parliament are ultimately political, not legal. But the principle of legality means that Parliament must squarely confront what it is doing and accept the political cost. Fundamental rights cannot be overridden by general or ambiguous words. This is because there is too great a risk that the full implications of their unqualified meaning may have passed unnoticed in the democratic process. In the absence of express language or necessary implication to the contrary, the courts therefore presume that even the most general words were intended to be subject to the basic rights of the individual.

Latterly, the principle of legality has been recast as one governing the relationship between the legislature, the executive, and the courts, 74 and that recalibrated rationale acts to strengthen the judicial commitment to the principle. Lord Hoffmann stated that the principle was ‘a presumption of general application operating as a constitutional principle’. 75 In agreement, and questioning the modern moniker, Sales LJ suggested that, ‘[i]t might be better expressed as the principle of respect for constitutional rights and principles’. 76 In the Electrolux case, the High Court of Australia described the principle as a central aspect of the rule of law. 77 As Gleeson CJ opined 78 :

the presumption is not merely a common sense guide to what a Parliament in a liberal democracy is likely to have intended; it is a working hypothesis, the existence of which is known both to Parliament and the courts, upon which statutory language will be interpreted.

In applying the principle of legality, courts tend to follow a threefold process. First, the fundamental rights, freedoms or values that have been breached or are at risk of infringement through action regulated by a statute or executive action, must be identified. 79 Second, a court will ascertain whether the relevant legislation interferes with this right. 80 Third, a court will assess whether the principle of legality operates to constrain any interference with the fundamental right. Note, the precise approach that courts take to each of these three steps varies between jurisdictions and between categories of case, as we discuss briefly in Part 6. 81 Further, in relation to the third step, the nature and content of a statute will affect the impact of the principle of legality and the outcome in the case. The legislature may have deliberately intended to breach rights. For example, specific legislation may have been promulgated to protect existing polluters, despite the impact on rights. However, that fact does not change the operation of the three-step process set out above.

Critically, Joseph states, ‘[t]he more important the right and/or the more intrusive the legislation, the stronger the presumption is against the statutory abrogation or limitation of it’. 82 Explicit language will be required to abrogate a fundamental right and, as Kiefel J observed in X7 v Australian Crime Commission 83 :

[t]hat is not a low standard. It will usually require that it be manifest from the statute in question that the legislature has directed its attention to the question whether to so abrogate or restrict and has determined to do so.

Which rights, freedoms or values will suffice to meet the first stage of the test is contestable. 84 Courts will readily employ the principle in respect of rights already recognised by the courts as fitting within the recognised class of fundamental rights, 85 including: personal rights, such as personal liberty, 86 freedom of movement, 87 and freedom of expression 88 ; property rights, such as the right from alienation of property without compensation 89 and the enjoyment of privacy and property free from intrusion 90 ; procedural rights, such as the right to procedural fairness 91 ; and, in the New Zealand context, the cultural rights of Māori people. 92

There is no clear methodology for how and when a right or freedom becomes fundamental at common law, and ‘what rights and freedoms are recognised as fundamental at common law is ultimately a matter of judicial choice’. 93 However, as with all common law developments, there is scope for the rights protected by the principle to expand and change over time. In the UK context, Varuhas notes the expansion of coverage from protected private rights to wider values and constitutional principles. 94 In the case of Fitzgerald v R , decided in 2021 by the New Zealand Supreme Court, Winkelman CJ stated the principle of legality was ‘not displaced or confined by statutory bills of rights and continues to develop’. 95 As one of us has argued elsewhere, the principle might also develop to protect rights already recognised within international human rights law, such as the right to life and rights specifically related to climate change, such as the right to a safe climate. 96

In practice, the principle of legality enables courts to give words their least rights-infringing meaning, to read down literal meaning, and to making statutes subject to some unexpressed qualification. 97 Further, the application of the principle of legality can arise in any statutory context, including criminal, administrative and private law. 98 Judges have a whole suite of tools of statutory interpretation available to them, different tools may be appropriate in different circumstances, and the choice of one tool over another can lead to different interpretative results. 99 However, in cases where rights are impacted, the principle of legality facilitates a clear, principled approach to legal reasoning, as we explain below.

With the link between climate change and fundamental rights firmly established, can we now propose that to protect rights courts should prefer legislative interpretation that promotes limiting greenhouse gas emissions or fostering adaptation to climate change wherever possible? In this part of the article, we undertake thought experiments to show the utility of our argument. First, we first consider a real case: Greenpeace v Genesis decided by the New Zealand Supreme Court in 2008. 100 The parties in Greenpeace did not advance any rights-based arguments (perhaps due to the age of the case). However, Greenpeace provides a good example of where our argument could have facilitated both a climate-protective result and clarified the legal reasoning in the case. Second, we provide select examples of other regulatory schemes that might be susceptible to our ‘climate-rights-interpretation’ argument.

In Greenpeace , the applicants, Genesis Power, wanted to establish a gas-fuelled power station that would emit millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases and other pollutants over its lifetime. The relevant environmental planning legislation—the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA)—has a statutory purpose of promoting the ‘sustainable management of natural and physical resources’, 101 and creates a statutory presumption against any industrial air pollution. Accordingly, the applicants would have to apply for specific consent to pollute. Consent to pollute is determined under s 104, that is expressly ‘subject’ to the sustainable management purpose of the Act. Before applying for consent, the applicant sought a declaration in relation to the meaning of s 104E of the RMA. Section 104E adds an additional legal test to the criteria that the consenting authority must follow in s 104. For present purposes, the contentious wording in s 104E was, when considering an application that would emit greenhouse gases, ‘a consent authority must not have regard to the effects of such a discharge on climate change ’. 102

These words clearly constitute a prohibition but in the Greenpeace case there was a dispute about what precisely they were prohibiting. The parties argued two conceptually distinct meanings. The first possible meaning was that an activity’s climate change-forcing impact should be disregarded—the result being that fossil fuel-use would be a neutral consideration in the consenting process. However, the alternative meaning was that decision-makers should not attempt to (re)evaluate the effects of greenhouse gases on climate change, that is, they should not debate whether greenhouse gases actually lead to climate change, or how this particular activity’s emissions would impact the climate (which, as Chief Justice pointed out in her judgment, would be impossible to do). That meaning would allow decision-makers to take in to account the climate change-forcing aspects of developments that emitted greenhouse gases but not open-up the whole issue as to whether emissions led to climate change—rather, that fact should be taken as read.

Over the course of the litigation, nine appellate judges considered this section, some of them more than once, and there was a divergence of views, particularly given the purpose of the Act to promote sustainable management. In the Supreme Court however, the majority found in favor of the first meaning, that is, the climate change-forcing aspect of the proposal must be ignored by the decision-maker. The majority adopted a confined, textualist approach to statutory interpretation. 103 In dissent, and adopting a purposive approach, the Chief Justice found in favor of the alternative meaning. Her Honour said that consent authorities must consider an activity’s emissions and their impact on climate change as a negative factor in the consenting process. That approach was, in her opinion, the only way to promote the sustainable management purpose of the Act.

Latter academic comment notes the divergent approach to statutory interpretation in the Supreme Court. 104 Clearly, the decision reflected individualised preferences, with different judges prioritising one mechanism of interpretation over another and there was a lack of unifying principle in the case. As we explained, counsel did not advance nor did the Justices invite submissions on wider doctrine. There was certainly no suggestion of the statutory provision raising a human rights issue or impacting on fundamental norms and values of the common law. However, given the clear linkage between climate change and human rights, what would have happened if the principle of legality had been employed to present a rights-based argument to the Court?

If our ‘climate-rights-interpretation’ argument had been made, opponents could have argued, ‘where the text of a statute presents constructional choices, the principle of legality will favor that choice which least disturbs common law freedoms’, 105 that is, that the statute requires the consent authority to consider greenhouse gas emissions because their impact on climate change imperils fundamental human rights. The Court would have been required to consider the three-step process set out in part three above by: first, identifying rights at risk; second, considering whether the legislation interferes with those rights; and third, assessing whether the principle of legality operates to constrain any interference with those rights.

While there are undoubtedly complexities to address in this re-imagining and much would depend on the specific evidence and submissions, 106 Greenpeace provides an accessible example of how the principle of legality might shift legal reasoning—requiring those interpreting statutes to do so in a way that best addresses the preservation of rights in the face of climate change. In the Greenpeace case, the principle might also have acted as the touchstone for reasoning lacking in the disparate judgments. The conclusions reached by judges in relation to each of the three steps may well differ, but all would be using the same tool, so allowing for a principled approach to legal reasoning. In future cases, when questions arise as to how to interpret legislation in the face of climate-rights arguments, the principle of legality can provide a doctrinally defensible and unifying approach to legal reasoning.

The application of the principle of legality can clearly extend beyond the statutory provision and the facts in the Greenpeace case. Whilst the climate change-rights linkage appears most readily in planning, development, and environmental law, contextually it could apply whenever climate change exacerbation, mitigation, or adaptation is factually in issue. In the New Zealand context, for example, a myriad of legislative schemes could be susceptible to a principle of legality analysis that links human rights and climate change. Examples include legislative schemes concerning special planning provisions 107 ; infrastructure development 108 ; investment 109 ; conservation 110 ; company 111 ; and even criminal law. 112 In respect of the latter, principle of legality-reasoning might be used to redefine statutory tests, such as the defence of ‘necessity’. Over the last few years, a number of climate change protestors in New Zealand have been charged with offences under the Trespass Act 1980. 113 Section 3(2) of that Act states:

It shall be a defence to a charge under subsection (1) if the defendant proves that it was necessary for him to remain in or on the place concerned for his own protection or the protection of some other person, or because of some emergency involving his property or the property of some other person.

Although, rights-based jurisprudence has not yet developed in New Zealand in this context, arguing a defence of necessity premised on the climate change emergency appears to be an emerging trend, globally. In the UK, some magistrates and juries are delivering not guilty verdicts for climate change activists accused of trespass and criminal damage, despite judges advising the jury, where there is one, to reject defences of climate necessity as not validly based in existing jurisprudence—a phenomenon termed ‘jury nullification’. 114 In other nations, legal defences based on climate necessity are gaining traction, and some appear to have met with success. 115 As argued by one of us elsewhere, a principle of legality analysis that links human rights and climate change in the Australian context could be engaged in the interpretation of legislation which creates offences for protestors seeking to disrupt operations at a coal mine. 116 This would necessitate consideration of the operation and effect of that legislation in order to answer the question of whether it impermissibly burdens the recognised fundamental right to freedom of expression and the implied freedom of political communication. Readers will no doubt see other possibilities in legislative schemes in other jurisdictions.

We have shown in the previous section how principle of legality-reasoning can be beneficial in upholding rights at risk from climate change. However, the question remains: what real value is there in focusing upon the common law principle of legality? Not all, but many of the types of decisions discussed above (including the decision of the consenting authority considered in Greenpeace ), will be made by the executive or constitute ‘public function-decisions’, and decision-makers are subject to direct duties under the relevant statutory bills of rights legislation to uphold statutory rights. A failure to do so may found a basis for judicial review. 117 Accordingly, public lawyers will no doubt ask: ‘what conceptual work could the principle of legality actually do here?’ Moreover, statutory bills of rights may have greater strength in protecting rights. As the NZ Supreme Court has accepted, the statutory bill of rights in New Zealand mandates a more proactive approach to interpretation than ‘orthodox formulations of the principle of legality’ by 118 :

proactively seeking a rights consistent meaning... [and]...“allows for reading down otherwise clear statutory language, adopting strained or unnatural meanings or words, and reading limits into provisions”.

Nevertheless, we suggest four reasons not to overlook the possible role of the principle of legality in infusing climate change impacts into statutory interpretation through a rights-protective construction.

First, the principle of legality persists through time and pervades judicial reasoning. In turn, it provides a means of non-regression, potentially cushioning rights-based reasoning from any roll back on statutory rights-protections. 119 By way of example, consider the current proposals in the UK to repeal and replace the Human Rights Act 1998. In June 2022, the Government introduced the Bill of Rights Bill to the Parliament and while the Bill would retain the suite of EU Convention rights in domestic legislation, it would remove the duty on courts to interpret legislation compatibly with those Convention rights. 120 There have been serious criticisms of the Bill of Rights Bill from many sectors of society and at the time of writing the progress of the Bill has been paused. 121 Nevertheless, in the event of the Bill progressing in its current form, and s 3(1) of the Human Right Act being repealed, the common law principle of legality will assume heightened importance in the UK as a judicial means for protecting fundamental rights. This is because repealing the Human Rights Act cannot repeal the existing common law principle; it will still exist and operate as a brake on legislation.

The second reason is that the principle of legality fills in the interstices left by statutory bills of rights. If a statutory bill of rights exists to regulate acts of government and those with public duties, one may not need recourse to the principle because the breach will be determined by the statutory provisions. Nevertheless, even in those circumstances the principle can act as a backstop in three ways. First, it can be used to interpret statutory bills of rights in the event of specific interpretative provisions not existing or being removed from those statutes (as is the case with the UK proposals). Second, it may be used to expand coverage over different actors, acts and omissions. With statutory bills of rights, one must first consider if a specifically regulated government authority has apparently acted incompatibly with the relevant bill of rights. Only then does judicial reasoning shift to considering the interpretation of the empowering legislation. 122 With the principle of legality, the requirement that the breach be committed by a specific category of regulated actor is not required. Accordingly, the principle may have a wider reach in terms of whose actions it can apply to, including private corporations. Third, the principle of legality has potentially a wider scope than statutory bills of rights, by expanding upon the suite of rights protected under those Acts, and by protecting rights that may be important in the climate change context. For example, the right to property is commonly omitted from statutory bills of rights 123 but in the climate change context, there may be clearer scientific evidence in specific cases concerning the adverse impacts on property (what, where, and how property will be impacted) than there is concerning its impact on the loss or impairment of life. The right to private property is a fundamental common law right, characterised by Blackstone as an absolute human right, 124 and has traditionally been strongly supported by the principle of legality. 125 It is not the role of this article to unpack the right to property but the actual physical loss of land resulting from runaway climate change could provide a basis for allegations of breach in a principle of legality analysis. Further, as a common law mechanism, there is scope for the range of rights protected by the principle of legality to grow, as Winkelman CJ noted in Fitzgerald . 126 In particular, the principle is arguably capable of expanding to encompass rights protected under international human rights treaties and developing climate change rights. 127 In the event of statutory bills of rights being amended or repealed (as is the possibility in the UK) one can imagine the principle would develop to encompass the right to life, which has been described as ‘the most fundamental of the rights’ and ‘an absolute right’. 128 The right to life has been interpreted to include the right to a quality environment, such as a healthy environment, in which to live. 129

The third reason is that the value of the principle is not just in preferential outcomes, it can also lead to deeper and more consistent analysis in the interpretative process. Classical versions of the principle of legality have organisational force in legal reasoning as the principle establishes a clear methodology for courts to follow. To quote Gans, writing in the Australian context, ‘[t]he principle’s rule like operation permits courts to make exceptionally clear statements about why they opt for a particular reading of a statute’ 130 Think again about the Greenpeace case discussed above. Drawing on the principle of legality may have provided the capstone under which legal reasoning could coalesce and introduced a clarity lacking in the disparate judgments.

The fourth reason is that classical versions of the principle of legality are not diluted by a proportionality test. Undoubtedly, question of proportionality constitutes the most intriguing aspect of the principle: should a principle of legality methodology incorporate proportionality? And if so, what form should that proportionality analysis take? Traditionally, the principle of legality did not incorporate any form of proportionality test. 131 In contrast, statutory bills of rights provide for ‘ reasonable protection for rights’. 132 That is, they contain limitation provisions that direct courts to consider the legislative policy behind the rights-infringing statute and, if it is justified, apply the transgressing text regardless. The rationale for this approach relies upon an admix of constitutional principles (parliamentary supremacy, and a correct understanding of the way various sections in Bill of Rights instruments work together) and realpolitik (rights are not absolute and resources available to ensure rights-protections are not unlimited). Justification is tested against a particular measure or standard, that is, proportionality.

However, courts in New Zealand and Australia have not explicitly grafted a proportionality test onto principle of legality-reasoning. 133 The principle is employed to determine the legal meaning of a statutory provision, not to evaluate whether a policy choice to abrogate rights could be justified. As Meagher argues, a proportionality inquiry is of necessity context and case specific, and conflating principle of legality-reasoning with a proportionality test would obscure the common law rights of which Parliament is supposed to be cognisant in legislating. 134

In the UK, we see a different approach where the Supreme Court has developed the methodology of the principle of legality to include a form of proportionality in administrative law cases. Varuhas terms this approach, an ‘augmented’ principle of legality, and notes it has provided greater protection for rights in some cases. For example, where the legislature has provided clear and express words abrogating rights of access to justice, the UK Supreme Court has applied a test of ‘least intrusive means’, 135 meaning that ‘rights may be curtailed only by clear and express words, and then only to the extent reasonably necessary to meet the ends which justify the curtailment’. 136 Further, ‘disproportionate interference [with fundamental rights]... can only be sanctioned by statutory words specifically authorising disproportionate interferences’. 137 In the ‘prisoners cases’ concerning delegated legislation, general words that would require deference in substantive review are susceptible to a principle of legality analysis without deference, because statutory interpretation is for the courts not the executive in the UK. 138

The differences in content and application of the principle of legality evidences the importance of legal culture and the type of right infringed is also important. However, if the principle of legality was to be subject to a proportionality test, we can imagine this might create an analytical pressure point in the climate change context—is the rights-infringing provision proportionate? We cannot give an answer to that question in the abstract: proportionality analysis invariably requires ‘judges to answer questions that are more political and philosophical than legal’, 139 and a judge may be receptive to or confronted by such value-infused analysis depending upon the legal and cultural context. 140 If proportionality is to be grafted on to a principle of legality-test, this fourth step would undoubtedly enrich the doctrine, but suffice to say it is a matter of general academic debate as to whether the principle should be subject to proportionality at all.

The principle of legality undoubtedly raises fundamental questions about the rule of law. It is trite to state that it brings into stark relief the tension between constitutional theorists and re-ignites arguments about the indeterminacy of rights. 141 Its use in the climate change sphere is likely to create resistance from the powerful sectors who profit from the polluting activity that causes climate change, and of course there is a risk that it could be weaponised by those entities. They might, for instance, seek to invoke the principle to protect their property interests in fossil fuels or as supporting deforestation. There are also very specific doctrinal debates about when the principle should be engaged, the rights it protects, and its scope and content.

But should these questions and debates prevent the principle of legality being raised and carefully debated in statutory interpretation when climate change impacts on rights, or indeed the relevance of enumerated rights or rights contained in international treaty law, are in issue? Arguably not, and indeed all three approaches may often be compatible and employed together where possible. We are at a moment in time when rights are not only at risk but lives are being taken by climate change, and it would be legally and perhaps constitutionally wrong if the judiciary did not consider seriously arguments linking climate change, the abrogation of fundamental rights, and the construction of statutes.

Nicholas Stern ‘The Economic of Climate Change: The Stern Review’ (CUP 2007); Dieter Helm and Cameron Hepburn (eds) ‘The Economic and Politics of Climate Change’ (OUP 2011); Stuart Mackintosh ‘Climate Crisis Economics’ (Routledge 2021).

Joanna Bell and Elizabeth Fisher ‘The Heathrow Case in the Supreme Court: Climate Change Legislation and Administrative Adjudication’ (2023) 86 MLR 226 quoting Elizabeth Fisher, Eloise Scotford and Emily Barritt ‘The Legally Disruptive Nature of Climate Change’ (2017) 80 MRL 173.

Elizabeth Fisher ‘Going Backward, Looking Forward: An Essay on How to Think about Law Reform in Ecologically Precarious Times’ (2022) 30 NZULR 111; Elizabeth Fisher ‘Law and Energy Transitions: Wind Turbines and Planning Law’ (2018) 38 OJLS 528, 529–530.

We acknowledge that there will be many other ways for climate change considerations to become embedded within the ‘substructure’ of the law, most critically through direct importation into codified constitutions or, in the UK and New Zealand, via climate change statutes becoming constitutional in nature.

For example, s 3(1) Human Rights Act 1998 (UK); s 6 New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1991 (NZ).

Fitzgerald v R [2021] NZSC 131, [51].

Bell and Fisher (n 2) 12.

Kim Bouwer ‘The Unsexy Future of Climate Change Litigation’ (2018) 30 JEL 483, 504; Brian J Preston, ‘Climate Conscious Lawyering’ (2021) 95 Australian Law Journal 51.

Preston, ibid, 51.

For example, Öneryıldız v Turkey , Application No. 48939/99 (20 November 2004); López Ostra v Spain , Application No. 16798/90 (9 December 1994); Fadeyeva v Russia [2005] ECHR 376; (2007) 45 EHRR 10.

For the voluminous academic commentary on the issue, see for example, Stephen Humphreys (ed) Human Rights and Climate Change (CUP 2010); John Knox ‘Linking Human Rights and Climate Change at the United Nations’, (2009) 33 Harvard Environmental Law Review 47; John Knox ‘Human Rights Principles and Climate Change’, in Cinnamon Carlarne, Kevin Gray and Richard Tarasofsky et al (eds) Oxford Handbook of International Climate Change Law (OUP 2016); Sumudu Atapatta Human Rights Approaches to Climate Change (Routledge 2015); Alan Boyle ‘Human Rights and the Environment: Where Next? (2012) 23 EJIL 613; Alan Boyle ‘Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Human Rights’ in Markus Kaltenborn, Markus Krajewski, Heike Kuhn (eds) Sustainable Development Goals and Human Rights (Springer 2020); Margaretha Wewerinke-Singh ‘Litigating Human Rights Violations Related to the Adverse Effects of Climate Change in the Pacific Islands’ in Jolene Lin and Douglas A Kysar (eds) Climate Change Litigation in the Asia Pacific (CUP 2020); David R Boyd The Environmental Rights Revolution: A Global Study of Constitutions, Human Rights, and the Environment (UBC 2011); Ademola Oluborode Jegede ‘Arguing the Right to a Safe Climate under the UN Human Rights System (2020) 9 International Human Rights Law Review 184; contributors to (2010) 38 Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law, Daniel Bodansky (ed) ‘Special Issue: International Human Rights and Climate Change’; contributors to (2009) 18 Transnational Law and Contemporary Problems ‘Special Issue: Climate Change and Human Rights Symposium’; UNEP Climate Change and Human Rights (UNEP, December 2015).

Paris Agreement , opened for signature 16 February 2016, UNTS I-54113 (entered into force 4 November 2016) Preamble. Note, however, many commentators have expressed disappointment that human rights are not mentioned in the text of the Paris Agreement see for example, contributors to (2019) 9 Climate Law ‘Special Issue: Implementing the Paris Agreement: Lessons from the Global Human Rights Regime’, Annalisa Savaresi and Joanne Scott (eds).

UN HRC Res 7/14 (27 March 2008) reprinted in UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Human Rights Council on its Seventh Session, 39–45, UN Doc A/HRC/7/78 (14 July 2008); UN HRC Res 10/4 (25 March 2009), reprinted in UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Human Rights Council on its Tenth Session, 65–66, 14 UN Doc A/ HRC/10/L.11 (12 May 2009).

For example, General Assembly of the Organization of American States, Human Rights and Climate Change in the Americas , OAS Doc. AG/RES. 2429 (XXXVIII-O/08), adopted at the Fourth Plenary Session, held on 3 June 2008; African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Climate Change and the Need to Study its Impacts in Africa , adopted at the 46th Ordinary Session on 25 November 2009; see also Environment and Human Rights (State Obligations in Relation to the Environment in the Context of the Protection and Guarantee of the Rights to Life and to Personal Integrity—Interpretation and Scope of the Articles 4(1) and 5(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights), Advisory Opinion OC-23/17.

UN HRC, Views adopted by the Committee under article 5(4) of the Operational Protocol, concerning communication No , Comm No. 2751/2016), UN Doc CCPR/C/126/D/2751/2016 (9th August 2019) at [2.3] (state’s failure to take action against environmental harm can violate its obligations to protect the rights to life (Art 6) and to private and family life (Art 17) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights).

UN HRC Views adopted by the Committee under article 5(4) of the Operational Protocol, concerning communication No. 2728/2016 , UN Doc CCPR/C/127/D/2726/2016 (24th October 2019).

ibid [8.6]. Note also the NZ Supreme Court did not rule out the possibility that environmental degradation resulting from climate change or other natural disasters could ‘create a pathway into the Refugee Convention or other protected person jurisdiction’ in Teitiota v Chief Executive of Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment [2015] NZSC 107, [13].

UN HRC Views adopted by the Committee under article 5(4) of the Optional Protocol, concerning communication No 3624/2019 , UN Doc CCPR/C/135/D/3624/2019 (‘ Torres Strait Eight v Australia ’) (22nd September 2022).

ibid [8.12]–[8.14].

ibid [8.7].

ibid Annexes I and III.

Leghari v Federation of Pakistan 2018 LHC 132.

State of the Netherlands (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy) v Stichting Urgenda Supreme Court of the Netherlands 19/00135, 20 December 2019.

Jaqueline Peel and Hari Osofosky ‘A Rights Turn in Climate Change Litigation?’ (2018) 7 TEL 37.

For example, Annalisa Savaresi and Juan Auz ‘Climate Change Litigation and Human Rights: Pushing the Boundaries’ (2019) 9 Climate Law 244; Annalisa Savaresi and Joana Setzer ‘Rights-based litigation in the climate emergency: mapping the landscape and new knowledge frontiers’ (2022) 13 Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 7.

Brian J Preston and Nicola Silbert ‘Trends in Human Rights-Based Climate Litigation’ (2023) 49 Monash ULR, forthcoming.

For example, Neubauer v Germany , Bundesverfassungsgericht [German Constitutional Court] 1 BvR 2656/18, 24 March 2021, [148]; Urgenda (n 24) [5.6.2]; Friends of the Irish Environment CLG v Government of Ireland Irish Supreme Court 205/19, 31 July 2020 [8.14]; Friends of the Earth Netherlands (Milieudefensie) v Royal Dutch Shell District Court the Hague C/09/571932/HAZA19-379, 26 May 2021 [4.4.28] (Note, the case is on appeal to the Dutch Supreme Court); Leghari (n 23) [12]; Bernard v Duban Papua New Guinea National Court of Justice N6299, 27 May 2016 [106]; Morua v China Harbour Engineering Co (PNG) Ltd Papua New Guinea National Court of Justice N8188, 7 February 2020 [56]; Farooque v Government of Bangladesh (2002) 22 BLD (HCD) 345 (Supreme Court of Bangladesh); Court (on its own motion) v State of Himachal Pradesh National Green Tribunal of India Application No 237 of 2013, 6 February 2014; Mansoor Ali Shah v Government of Punjab (through Housing, Physical and Environmental Planning Department) 2007 CLD 533 (Lahore HC) [11].

For example, Future Generations v Colombian Ministry of the Environment Supreme Court of Columbia STC4360-2018, 5 April 2018 (key excerpts from the unofficial translation); Juliana et al v United States 217 F Supp 3d 1224.

For example, Gbemre v Shell Petroleum Development Company Nigeria Ltd (2005) AHRLR 151 (Nigeria HC) [5(4)]; Future Generations 35[11.3] and [12] (key excerpts from the unofficial translation).

For example, Kreishan v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 2019 FCA 223, [2020] 2 FCR 299.

[139]; Mathur et al v Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Ontario 2020, ONSC 6918 [159].

VZW Klimaatzaak v Kingdom of Belgium French-speaking Court of First Instance of Brussels, Civil Section 2015/4585/A, 17 June 2021, [2.3.1.].

Torres Strait Eight (n 19) [8.12–8.14].

For example, Smith v Fonterra Co-operative Group Ltd [2020] NZHC 419 [5-10] (case currently on appeal to the NZSC) [5-10]; ADPF 746 (Fires in the Pantanal and the Amazon Forest) Brazil Federal Supreme Court, ADPF 746, filed 24 September 2020; see also Torres Strait Eight, ibid.

Including a swathe of cases from young people filed in the ECtHR and elevated to the ECtHR Grand Chamber for hearing, for example, Duarte Agostinho and Others v Portugal and 32 Other States , European Court of Human Rights, Application No 39371/20, filed 2 September 2020; Soubeste and Others v Austria and 11 Other States , European Court of Human Rights, Application No 31925/22, filed January 2022; De Conto v Italy and 32 Other States, European Court of Human Rights, Complaint No 14620/21, filed 3 March 2021; see also ongoing litigation in Juliana (n 29).

Lliyua v RWE AG (Higher Regional Court Hamm, 30 November 2017).

For further discussion, see Brian Preston ‘The Evolving Role of Environmental Rights in Climate Change Litigation’ (2018) 2 Chinese Journal of Environmental Law 131, 157-162.

Neubauer (n 28). For analysis see Petra Minnerop ‘The ‘Advance Interference-Like Effect’ of Climate Targets: Fundamental Rights, Intergenerational Equity and the German Federal Constitutional Court’ (2022) 34 JEL 135.

ibid [122], [182]–[183].

Milieudefensie (n 28). For analysis see Chiara Macchi and Josephine van Zeben ‘Business and human rights implications of climate change litigation: Milieudefensie et al v Royal Dutch Shell’ (2021) 30 RECIEL 409.

ibid [2.4.13], [4.4.10].

ibid [4.4.10].

ibid [4.4.55].

Waratah Coal Pty Ltd v Youth Verdict Ltd and Ors (No 6) [2022] QLC 21.

Waratah Coal Pty Ltd v Youth Verdict Ltd and Ors [2020] QLC 33.

Waratah (n 44) [1346], [1352].

Mathur (n 31).

ibid [153].

ibid [156].

ibid [159].

In contrast, rights-based litigation in jurisdictions without entrenched constitutional rights has proven less successful to date, see for example, Preston and Silbert (n 27).

For example, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature 19 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, opened for signature 19 December 1966, 993 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 January 1976); International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, opened for signature 7 March 1966, 660 UNTS 195, entered into force 4 January 1969; Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, opened for signature 1 March 1980, 1249 UNTS 13 (entered into force 3 September 1981); Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 10 December 1984, 1465 UNTS 85 (entered into force 26 June 1987) (Convention against Torture); Convention on the Rights of the Child, opened for signature 20 November 1989, 1577 UNTS 3 (entered into force 2 September 1990); Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, opened for signature 30 March 2007, 2515 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 May 2008) (Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities).

For instance, many of the provisions in the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities are incorporated in Australian law through the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth). The Human Rights Act 1998 (UK) incorporates the rights set out in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) into British law. The scope of the ECHR is similar to that of the ICCPR. The Crimes of Torture Act 1989 (NZ) implements New Zealand’s obligations under the Convention against Torture.

For example, Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) s 32(2); Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld), s 48(3); Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT), s 32(1).

For example, New Zealand Airline Pilots’ Association Inc v Attorney-General [1997] 3 NZLR 269 (NZCA), 289; Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Teoh (1995) 183 CLR 273, 287; Al-Kateb v Godwin (2004) 219 CLR 562; [2004] HCA 37 [193] (Kirby J); Momcilovic v The Queen (2011) 245 CLR 1; [2011] HCA 34 [18]; Ahmad v Inner London Education Authority [1978] QB 36 (UKCA), 48 (Scarman LJ). Note also, The Balliol Statement of 1992 67 ALJ 67 (duty of judiciary to interpret the law in accordance with International Human Rights Treaties). Note this approach to interpretation in often termed a principle of legality approach too, see for example, Students for Climate Change Solutions v Minister of Energy and Resources [2022] NZHC 2116 [91].

Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic), s 32(1); Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld), s 48(1)-(2); Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT), s 30.

For example, c.f., Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT), s 30 (‘So far as it is possible to do so consistently with its purpose, a Territory law must be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights’) with New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, s 6 (‘Wherever an enactment can be given a meaning that is consistent with the rights and freedoms contained in this Bill of Rights, that meaning shall be preferred to any other meaning’) and Human Rights Act 1998 (UK), s 3(1) (‘So far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights’).

For example, Hanna Wilberg ‘Pandemic Litigation Reaffirms Hansen Approach But Also Exposes Two Flaws In Its Formulation’ (2022) 30(1) NZULR 69; Dinah Rose and Claire Weir ‘Interpretation and Incompatibility: Striking the Balance’ in Jeffrey Jowell and Jonathan Cooper (eds) Delivering Rights: How the Human Rights Act is Working (Hart 2003).

For example, Fitzgerald (n 7)[48]; Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza [2004] UKHL 30; [2004] 2 AC 557 [26]. A climate change rights-based interpretative argument was raised in R (Friends of the Earth Ltd) v Heathrow Airport Ltd [2020] UKSC 52, [113] but not dealt with by the Supreme Court, as it had not been raised in the Court of Appeal. In R (Friends of the Earth, et al) v Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy [2022] EWHC 1841, the petitioners’ claims were successful, on an ordinary construction of the Climate Change Act 2008 (UK), and the Secretary of State ordered to re-write the carbon budget to align with the net-zero target in the Act. The rights-based arguments prayed in aide and premised on s 3(1) of the Human Rights Act 1998 were rejected with Holgate J discussing the subtleties of the statutory test at [265], ‘[i]t is only if the ordinary interpretation of a provision is incompatible with a Convention right that s.3(1) is applicable... [it] does not allow a court to adopt an interpretation of a provision different from that which would otherwise apply in order to be “more conducive” to, or “more effective” for, the protection of a Convention right, or to minimise climate change impacts.’ See also Lawyers for Climate Action NZ Inc (‘LCANZ’) v Climate Change Commission [2022] NZHC 3064 (fn 157): judicial review proceedings; LCANZ submitted legislation should be read compatibly with s 6 of NZBORA but could not suggest an alternative way of reading the statute from the way the Commission had, so Court did not address argument.

Dr Bonham’s Case (1610) 8 Co Rep 107a, 77 Eng Rep 638; James Bagg’s Case (1615) 11 Co Rep 93(b) 77 Eng Rep 1271.

For example, Minet v Leman (1855) 20 Beav 269; Cooper v Wandsworth Board of Works (1863) 14 CB (NS) (Common Pleas).

The most famous modern statement of the principle of legality is from the judgment of Lord Hoffmann in the UK case R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex Parte Simms [2000] 2 AC 115, 131–132. See, Dan Meagher ‘The Common Law Principle of Legality’ (2013) 38 Alternative Law Journal 209, 209–210.

For example, United States v Fisher 6 US 358 (1805), 390; Potter v Minahan (1908) 7 CLR 277, 304.

For example, Slaight Communications Inc v Davidson [1989] 1 SCR 1038; AG (SA) v City of Adelaide (2013) 249 CLR 1, 30, French CJ of the High Court of Australia confirmed that ‘statutes are construed, where constructional choices are open, so that they do not encroach upon fundamental rights and freedoms’.

National Assistance Board v Wilkinson [1952] 2 QB 648, 661 (Lord Devlin).

Brendan Lim ‘The Normativity of the Principle of Legality’ (2013) 37 Melbourne University Law Review 371; see also Stephen McLeish and Olaf Ciolek ‘The Principle of Legality and “The General System of Law”’ in Dan Meagher and Matthew Groves (eds) The Principle of Legality in Australia and New Zealand (Federation Press 2017).

Grant Gilmore, The Ages of American Law (Yale UP, 1977), 95.

Malika Holdings Pty Ltd v Stretton (2001) 204 CLR [28]–[29] (McHugh J). See also Andrew Burrows Thinking About Statutes: Interpretation, Interaction, Improvement (CUP 2018) 72.

P Sales, ‘Rights and Fundamental Rights in English Law’ (2016) 75 CLJ 86, 90.

Robert French ‘The Principle of Legality and Legislative Intention’ (2019) 40 Statute Law Review 40, 51.

Simms (n 64).

Edward Willis ‘Interpretive Presumptions: Catalysts for Constitutional Reasoning’ [2022] New Zealand Law Review.

Simms (n 64) [130 E].

P Sales ‘A Comparison of the Principle of Legality and Section 3 of the Human Rights Act 1998’ (2009) 125 LQR 598, 607. See also R v Secretary of State for the Home Dept, ex p Pierson [1998] AC 539 (HL), 575 (Lord Browne-Wilkinson), in the context of judicial review of administrative action, ‘[a] power conferred by Parliament in general terms is not to be taken to authorise the doing of acts by the donee of the power which adversely affect the legal rights of the citizen or the basic principles on which the law of the United Kingdom is based unless the statute conferring the power makes it clear that such was the intention of Parliament’.

Electrolux Home Products Pty Ltd v Australian Workers’ Union (2004) 221 CLR 309, [21] (Gleeson CJ).

Secretary, Department of Family and Community Services v Hayward (a pseudonym) (2018) 98 NSWLR 599; [2018] NSWCA 209, [39].

There is debate in both the scholarship and case law as to whether the principle can apply in the absence of legslative ambiguity. Lord Steyn opined that the principle applies even in the absence of textual ambiguity, Simms (n 64), 130 and see Philip Joseph ‘The Principle of Legality: Constitutional Innovation’ in Dan Meagher and Matthew Groves (eds) The Principle of Legality in Australia and New Zealand (Federation Press 2017) 39–40.

Jason Varuhas ‘The Principle of Legality’ (2020) 79 CLJ 578, 590 (describing three variants in approach: (1) express words are required to sanction interference with fundamental rights; (2) express words are insufficient to authorise disproportionate interferences; and (3) courts should pro-actively construe statutory text to limit interference as far as possible).

Joseph (n 80) 33 quoting Simms (n 64) 130.

X7 v Australian Crime Commission (2013) 248 CLR 92, [158]; [2013] HCA 29.

ibid; and see Dan Meagher ‘The Common Law Principle of Legality in the Age of Rights’ (2011) 35 Melbourne University Law Review 449.

Momcilovic (n 57) [444]; see also Hanna Wilberg ‘Interpreting Pandemic Powers: Qualifications to the Principle of Legality’ (2020) 31 Public Law Review 384, 385: ‘common law usually defines rights in terms of the elements of established wrongs or remedies as found especially in law of torts or habeas corpus’.